At first glance, Terlanenveld looks much like any other big field in the green belt around Brussels. Straddling a quiet lane off the scenic N4 road between Overijse and Wavre, its wide expanse of pasture is criss-crossed with paths popular with walkers, joggers and cyclists, especially at weekends.

But this is no ordinary field.

Terlanenveld was the site of one of the largest prisoner-of-war (POW) camps in western Europe. From March 1945 to August 1946, it held nearly 60,000 of the 250,000 German POWs incarcerated in Belgium.

They endured harsh conditions, overcrowding, brutal punishments for the slightest misdemeanour, and barely enough food to live on. Any sympathy for the defeated enemy was in very short supply – especially after the scale of the horrors unleashed by the Nazis at Auschwitz, Treblinka, Buchenwald and Belsen came to light.

Officially Prisoner-of-War Camp 2228, Terlanenveld was one of more than 40 POW and labour camps set up by the Allies in Belgium in the closing months of the war and immediate aftermath of Germany’s surrender. The British oversaw camps in Flanders and around Brussels, while the US military ran the camps in Wallonia.

It's a cold and wet day when I visit the site, accompanied by 68-year-old local historian Piet Van San, a retired former director of payroll admin company SD Worx.

Covering around 250 hectares, Terlanenveld occupies a relatively high strip of ground, more than 100 metres above sea level. The site is partially bordered on one side by trees but otherwise totally exposed to the elements. The wind whistles around us as we arrive at a small parking area close to what was the entrance barrier to the complex.

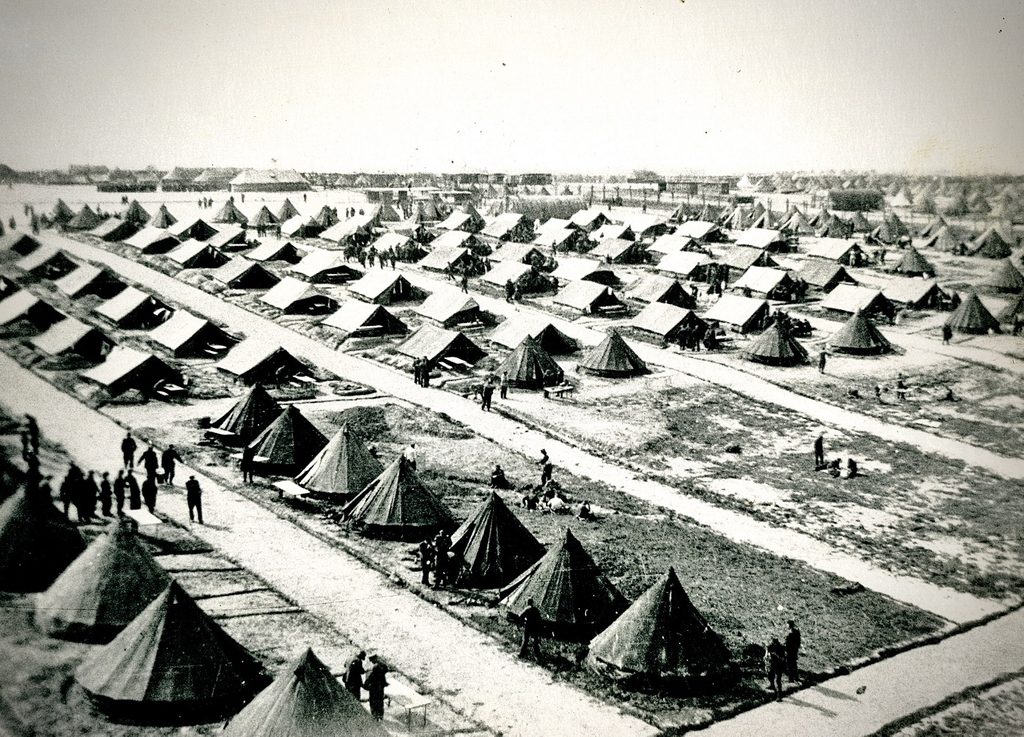

Van San points to an information board – one of nearly a dozen on the site – for which he provided content. It includes a photograph showing the camp as it looked in 1945. It is covered in row upon row of bell tents, as far as the eye can see. Each tent held at least 15 POWs. The prisoners would dig more than a metre into the ground before pegging the tents, in the vain hope of keeping out the cold and damp.

Enemies interned

They would arrive at the camp hungry and exhausted, having walked from the nearest railway station at La Hulpe about 10km away. The civilian population, who had endured their fair share of miserable hardship during years of occupation, was not averse to letting the vanquished enemy know what they thought of them.

Matters sometimes got out of hand.

In his book, De Tweede Wereldoorlog Overijse 1944-1945, Van San cites an incident witnessed by local resident Roger Dehaen, then 11 years old. “It was a Sunday evening, and we were watching an endless group of ragged, dead-tired soldiers pass by. They had few guards with them and some onlookers, who weren’t from the area, suddenly started to whip the startled POWs with leather belts. It was degrading. A young man, who was well-known to us from the resistance, couldn’t stomach it. He punched one of the culprits, knocking him over. The British guards finally put an end to the incident with a few blows from their rifle butts. I felt such disgust that I never went back to watch the prisoners’ passage again.”

Prison guards

Van San shrugs after reciting this passage. “There was a lot of hatred towards the Germans at first,” he says. A woman holding a straw effigy of Hitler with a noose around his neck was a regular sight on the roadside in Maleizen, between La Hulpe and Terlanen, as the POWs trudged en route to the camp.

Once inside, checks were carried out to ensure no officers or SS members (identifiable from a small blood group tattoo), trying to pass themselves off as regular Wehrmacht soldiers, were among the arrivals. Officers and German SS (different rules applied to non-German SS) were transferred straight to the UK. During registration, the prisoners’ names would be cross-checked against lists of war criminals.

They were then treated with delousing powder, aimed at killing off insects that transmitted diseases such as dysentery and typhoid.

At first, the daily food ration typically consisted of no more than 1,400 calories with a small piece of bread and margarine in the morning, a cup of watery vegetable soup at noon and bread and margarine in the evening. The rations were later increased to 2,000 calories a day.

Prisoners were entitled to send two letters home per month on a folding prisoner-of-war form. “They were censored, and the content generally looked very similar,” says Van San.

Rigid regime

The demoralised POWs were subject to strict and often arbitrary rules. Woe betide anyone who infringed them. “The Scottish guards were the roughest,” says Van San. “Prisoners who broke the rules would be stripped to the waist, tied to a stake and have buckets of freezing cold water thrown over them. They were hit with canes and often had dogs set on them.”

The treatment meted out to the POWs evolved over time. “It was hard but correct to start with, became increasingly problematic, but then more humane towards the end of the camp's existence,” Van San adds.

Prisoners

Representatives of the Red Cross visited Terlanenveld in September 1945 and advised the British commander to issue the prisoners with three blankets each and increase their meagre rations. Failure to act could result in a catastrophe as temperatures fell, they said.

The warnings were not heeded. At least 229 weakened POWs perished at Terlanenveld during the freezing winter of 1945-46, many from dysentery and typhoid. British newspapers, notably The Observer, condemned the spate of deaths and treatment of POWs, sparking questions in the House of Commons.

The dead were buried in a makeshift, padlocked cemetery at the back of the camp. The remains were later transferred to Brussels before being exhumed again and moved to Lommel, the site of the largest German military cemetery in western Europe outside Germany, with more than 39,000 burials.

Jacob Hirschfeld, a radio operator on U-boat 234 which surrendered to US forces off Maine nearly two weeks after Germany’s collapse, was transferred to Europe in April 1946. He arrived at Waterloo on a goods train with other POWs and walked 20km to Terlanenveld.

“We used our long coats as blankets,” Hirschfeld wrote. POWs had to hand over everything they owned, except personal photographs. The tents were full of water and rotten straw.

The tents stretching across the field

Trusted prisoners had taken over the task of handing out the rations. Morning and evening meals were provided together: each prisoner received a piece of bread, a small lump of margarine and a kilogram of meat, divided between 32 men. The lunchtime “water soup” was thickened with “all possible herbs such as nettles, dandelion and even grass”, Hirschfeld recalled.

One morning, the prisoners caught four of the better-fed German kitchen cooks embezzling meat. It caused a riot and the Scottish guards intervened forcefully.

Hirschfeld claims to have heard that 3,000 POWs starved to death at Terlanenveld in the winter of 1945-46 but that only 76 were buried in the cemetery. The rest were reported as having escaped or had their bodies burnt, he said.

Having studied countless testimonies, Van San questions these figures, pointing out there were almost no escapes or attempted escapes at Terlanenveld, although guards opened fire on two local women, a mother and daughter, after mistaking them for fugitives when they were working in a field next to the camp.

Rocket attacks

By January 1945, any lingering hopes in Berlin that Germany could turn the tide of the war had been extinguished. Hitler’s last gamble, a surprise Attack through the Belgian Ardennes, aimed at capturing Antwerp and forcing the allies into peace talks, was foiled in the Battle of the Bulge.

The Luftwaffe was barely operational, although Belgium was a target for long-range rocket attacks. The Cinema Rex in Antwerp took a direct hit from a V-2 missile on December 16, 1944, the first day of the Ardennes offensive. The cinema was packed for a Saturday afternoon screening of a Cecil B. DeMille western, The Plainsman. The deadliest rocket attack of the war, it left 567 dead, including 296 servicemen and 271 civilians, among them women and children. Hundreds were injured. Due to a news blackout, the scale of the tragedy was not reported at the time.

The increasing threat from V-1 and V-2 attacks meant that the over-stretched allies urgently needed to strengthen their air defences in Belgium. With the bulk of the troops committed to the crossing of the Rhine, units from Britain’s Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), made up of young, unmarried women aged 18 to 30, were deployed to crew anti-aircraft batteries around Brussels and Antwerp.

Churchill connection

Mary Churchill, the 22-year-old youngest daughter of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his wife Clementine, was put in command of an ATS battery at Terlanenveld and another nearby, arriving a few weeks before camp opened.

Her wartime diary, held by the Churchill Archives Centre in Cambridge, records that, after crossing the Channel from Southend, her unit was loaded onto trucks at Ostend and travelled via Bruges, Ghent, where they stopped for buns and tea, and Brussels, before finally reaching their snow-covered destination on January 28, 1945. The women were billeted with families in Overijse and Huldenberg.

The winter was so cold that oil in the guns' hydraulic systems froze at times, but Mary’s unit still managed to shoot down several rockets before they reached their intended targets in Brussels. Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery wrote to her in February, promising to send a case of Bovril and 10,000 cigarettes for the battery.

While on duty, the ATS girls, as they were universally known, would spend their nights in small, wood-built barracks next to the camp. A sign on the inside of the door to their dormitory suggests they didn’t always get much sleep: it read “Snoring Lane”. Mary was better off, staying at the château de Huldenberg as guest of the mayor, Count Thierry de Limburg Stirum and his wife Princess Marie Immaculée de Croÿ.

The Auxiliary Territorial Service women of Snoring Lane

“Mary and the ATS ladies lived a fairly carefree life, were liked by the locals, and often came into the village to grab a beer or attend dances. They could also buy English cigarettes for 100 Belgian francs a packet [about two euros at today’s prices],” says Van San.

Their life could not be more different than the prisoners.

The girls were in frequent demand for dances – and not just on the doorstep. In her journal, Mary recalls a memorable hop in Namur. “It was WOW,” she wrote. “I had a wonderful time – lots of good-looking young men – not too many girls and lovely champagne. Was thoroughly spoilt – flirted outrageously with anyone I fancied.” A first battery dance at Huldenberg, however, was “rather a flop”.

She had previously fallen for Jean-Louis de Ganay, a French aristocrat serving in the Special Operations Executive. Her diary records her “floundering” through mass at Huldenberg and having a heart-to-heart with another ATS girl, Joan, “as to whether to become RC [Roman Catholic] if I marry Jean-Louis – If I marry J-L.” In the event, they didn’t tie the knot but remained lifelong friends.

Away from her duties, Mary found time to see performances of Puccini’s La Bohème by Sadler’s Wells Ballet and Debussy’s Pélléas et Mélisande at the Thêatre Royal de la Monnaie, Bach’s Cantatas at the Palais des Beaux-Arts, went boar-hunting in the Ardennes, window shopping in Brussels’ Avenue Louise, and lunched with Belgium’s dowager Queen Elisabeth and the British Ambassador Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen at Laeken.

Louis Rigaux, a talented local artist in Overijse, photographed and painted portraits of the ATS girls, including Mary, who sat for him on April 8. She received orders to move her battery up to Antwerp ten days later.

Mary Churchill

Awarded the Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for her military service, Mary spent VE Day in Brussels, recalling a city “bedecked with flags” and vast crowds. “Every car and jeep was overloaded with children & grownups too clinging to the roof & sides … we went to the Grand Place – what a sight – flood-lighting, music, bells, but above all, people. Thousands of them – friendly, jostling, thankful crowds.”

Battle for Coal

It is not recorded how the POWs at Terlanenveld felt about VE Day and the cessation of hostilities. For them, the war was far from over.

Labour shortages, especially in the coal mining areas of Limburg and Wallonia, meant many POWs in Belgium were put to work. La Bataille du Charbon (the Battle for Coal) was a top priority for the country’s Prime Minister, Achiel Van Acker, who persuaded the Allies to provide him with extra manpower in the form of tens of thousands of prisoners.

The POWs also worked on farms, in the forests and on a variety of infrastructure projects. Prisoners from Terlanenveld rebuilt the marketplace in Overijse and laid out a new football ground, still in use today. German prisoners also built the 40,000-capacity Stade des Trois Tilleuls, home of Racing Club de Bruxelles, in Watermael-Boitsfort.

Life in the camp gradually began to improve after the outcry in the Commons. The bread ration doubled, and a kilogram of meat was now shared between eight instead of 32 prisoners. Sports and cultural activities were allowed. German music was piped through loudspeakers, there was a choir and a singing quintet called Swingtett. Two handball teams were formed.

Belgian fusiliers took over responsibility for manning the watchtowers and patrolling the double-lined barbed-wire perimeter fence, although the camp continued to be run by the British.

The Belgian sentries were more amenable than the British. According to Van San, on one occasion the Belgian guards invited around 30 prisoners who were working in Overijse for a beer at a café. “Afterwards, they all marched back to the camp together and the POWs carried the guards’ weapons for them. You can imagine how the British commander reacted,” he says.

While contact with POWs was strictly forbidden in the early days, the Belgians were willing to turn a blind eye to minor transgressions. Locals set up a barter trade, exchanging tobacco and food for watches, shoes and simple artworks made by the POWs. “The trades would happen at agreed places where the goods, weighted with a stone or stick, were thrown back and forth over the wire, with the tacit approval of the guards,” says Van San.

Many of the POWs spent at least another year in captivity or working as forced labour after the end of the war. It was not until August 5, 1946, that the last prisoners left the camp.

The Belgian military authorities finally closed the abandoned camp in September 1947. By then, in the words of Van San, it was “an incredible mess”. Although the local council employed security guards after the camp’s closure, anything of potential value which had been left behind quickly disappeared. The four-metre-high steel posts from the camp's fence were especially popular.

Robert Coelmont, the pastor of Jezus-Eik, who was held in a German prison camp during the war, asked if he could legally acquire a small wooden hut, but few of his flock followed his example. “There was a lot of stealing,” comments Van San.

Small artefacts, from battered mass tins to buttons, continue to emerge from the ground at Terlanenveld. Most end up at t’ Klein Verzet, a cosy Dijleland pub to which Piet Van San invites me after we visit the site. The owners, Dirk and Ingrid Jena De Wilde, have built a cabinet to house finds from the former camp.

Afterwards, at Van San’s home, he shows me some of his vast collection of photographs, newspaper clippings and original letters sent by POWs to their families in Germany. Acquired over many years, his meticulously curated archive includes hundreds of images of the camp and its guards, but few of the prisoners.

In 1986, former POWs and guards from Terlanenveld were reunited at a remembrance ceremony. “Most, if not all, must have sadly passed away now,” says Van San, a Mechelen native who moved to Overijse five years after the commemoration. “It’s a regret that I have never met any of the former POWs.”

However, his collection of pictures provides a stark reminder of a dark time in Europe’s history which surely all of those involved, whether victorious or vanquished, hoped would never be repeated. Some hope.

After the war

The first prisoners in the British zone were released as soon as autumn 1945. Priority was given to those aged 16-18. Helmut Stephan, who kept a diary during his captivity, left Terlanenveld on September 9. He was taken via Brasschaat (camp 2223) to Weeze in Germany, close to the Dutch frontier. “I left as a free citizen in uniform – my only possession apart from a bread pouch, a canteen, a comb, shaving kit, and my manuscripts from Camp 2228,” Stephan wrote.

From May 1946, prisoners underwent a medical examination. Those deemed “unhealthy” were allowed to return home. Wolfgang Hirschfeld was released on June 18 and taken via Brussels, Aachen and Köln to Munsterlager.

Once home, the former prisoners registered with the authorities and could begin the slow process of rebuilding their lives.

In July 1945, Winston Churchill, no longer Prime Minister, asked Mary to accompany him as his aide-de-camp when he met US President Harry Truman and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin at the Potsdam Conference.

In November, they returned to Brussels and Antwerp where Winston was greeted by ecstatic crowds. Mary enjoyed a “mild flirtation” with Prince Charles of Belgium but, returning to Brussels the following September for a painting trip with her father, was embarrassed over newspaper speculation that an engagement to the Prince Regent was imminent.

The same month, she met Christopher Soames, a Coldstream Guards Captain and assistant military attaché in Paris. He proposed twice, after being turned down at first. They wed in 1947, going on to have five children. Her husband successfully stood for the House of Commons in 1950, holding his seat for 16 years. He was British Ambassador to France from 1968-72 and, from 1973-77, the UK’s first European Commissioner, allowing Mary to rediscover her old wartime haunts.

Mary later became a successful author, writing a biography of her mother and her own memoirs, A Daughter’s Tale, which were published three years before her death, aged 91, in 2014.

The ATS girls in her unit stayed in contact for years, as well as with the Belgian families, they stayed with during the war. Piet Van San recalls how he and his wife Marleen received two unannounced, 90-something visitors, Lucy Bowyer and her husband Claude, one Sunday afternoon in August 2010.

“Lucy was stationed here from January 1945 as a member of the 137th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery 481 Battery. She had very happy memories of the time and spoke of Lady Mary Churchill in awe. She told us how the girls would get their laundry done in the village in exchange for chocolate and soap,” Van San says.

Van San accompanied the couple to the church cemetery in Terlanen where a soldier from Mr Bowyer's regiment, the Shropshire Light Infantry, is buried. “He paid his respects immaculately. It was a moment I will never forget,” Van San says.

Stung by beehive

The only other POW camp in Belgium with a comparable number of detainees to Terlanenveld was at Zeldegem, southwest of Bruges.

Located at Vloethemveld, on the site of a former ammunition depot, Zeldegem housed four separate camps (2226, 2227, 2229 and 2375) within its forested perimeter. Operational from February 1945 to September 1946, Zeldgem was recently at the centre of a storm of controversy.

The prisoners included nearly 12,000 Latvian Waffen-SS, who were commemorated in 2018 when the local council unveiled a monument entitled De Letse bijenkorf voor vrijheid (The Latvian Beehive for Freedom). The work, designed by acclaimed sculptor Kristaps Gulbis, was erected on the town’s Brivibaplein.

The beehive triggered a huge political row, with opponents instantly calling for its removal. "In our country, there is no place for a hate-mongering monument disguised as a work of art for freedom," said Belgian MP Vicky Reynaert.

Supporters from the Latvian diaspora, especially in the US, insisted that the Latvian Legion, as they prefer to call them, were patriots forced to fight alongside the Germans against the Red Army and that the vast majority were not Nazis. However, it is not disputed that at least a handful of the POWs at Zeldegem were active collaborators who supported – and may have participated in – notorious death squads such as Arājs Kommando, responsible for killing thousands of Jews and Roma.

The row was eventually settled in December 2021 when the town council convened an international expert panel, which recommended the removal of the “inappropriate” beehive while acknowledging the “complexity” of the historical context and suggesting that Vloethemveld could become “an innovative remembrance project of European significance, showing how it is possible to deal with the controversial legacies of the Second World War and the Cold War”.

The beehive is now hidden from sight in a municipal depot.