On this day 4 August 1914, Belgian newspapers broke the news that German troops had breached the Belgian border and started their invasion. The atrocities that they committed against the Belgian population as they marched across the country came to be known as the Rape of Belgium.

Around 6,500 civilians were killed in Belgium and northern France by the German army in the summer of 1914 under the policy of terror (schrecklichkeit). To justify and encourage their actions, a propaganda effort was weaponised against the victims.

Rumours of Belgian franc-tireurs (guerrilla fighters) targeting the invaders spread across the German Army. Stories were fabricated of Belgian civilians cutting the throats of sleeping soldiers and gouging their eyes out – which all fuelled the invading army's brutality against civilians. By contrast, a German pamphlet called The Mill in the Ardennes presented the German Army as well-behaved and selfless.

As the Germans marched towards the heavily-fortified city of Liège, they went from town to town, village to village, rounding up hostages and executing men, women and children, in some cases stabbing them with their bayonets.

The execution of Belgian officials of Blégny, 1914, by Evariste Carpentier (1845-1922).

Systematic plunder was rife. Soldiers stole food, cattle, horses, antiques and anything else of value. Innumerable bottles of wine and spirits were taken – with intoxicated soldiers becoming harsher as houses were set alight, women raped, and executions carried out en masse.

In the southern province of Luxembourg alone, around 3,000 houses were set on fire. Many villages, such as Hemeland and Rossignol, were completely razed by arson. Civilian executions in the province of Luxembourg alone amounted to 1,000. In Dinant, 612 were killed and 517 in Tamines.

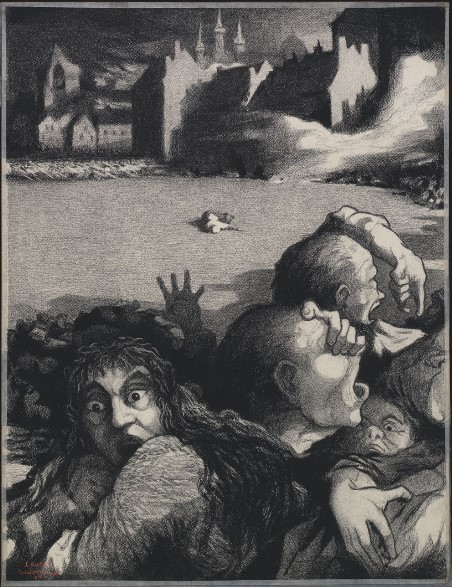

"Louvain" by Belgian painter Gisbert Combaz (1869-1941).

One of the most remarked-upon episodes took place in Leuven. On 19 August, around 15,000 German troops entered and occupied the city. They arrested municipal officials, academics and civilians and terrorised the local population by forcing them to keep their front doors open and windows lit throughout the night.

Despite facing no resistance from the city, soldiers kicked doors down and executed people on the spot, dumping them in mass graves. Many were sent to the train station where a firing squad or detention waited.

As Belgian refugees escaped, the world was shocked by their stories of brutality. Not only outraged by the human cost, the destruction of Leuven’s library – one of the oldest in Europe standing since 1636 – sparked international uproar after it was burnt down, with 230,000 books, 950 manuscripts and 800 pamphlets destroyed.

Civilian women pick their way over rubble and debris to reach a group of soldiers standing outside the ruined City Hall, Leuven, Belgium. Credit: Imperial War Museum

Propaganda wars

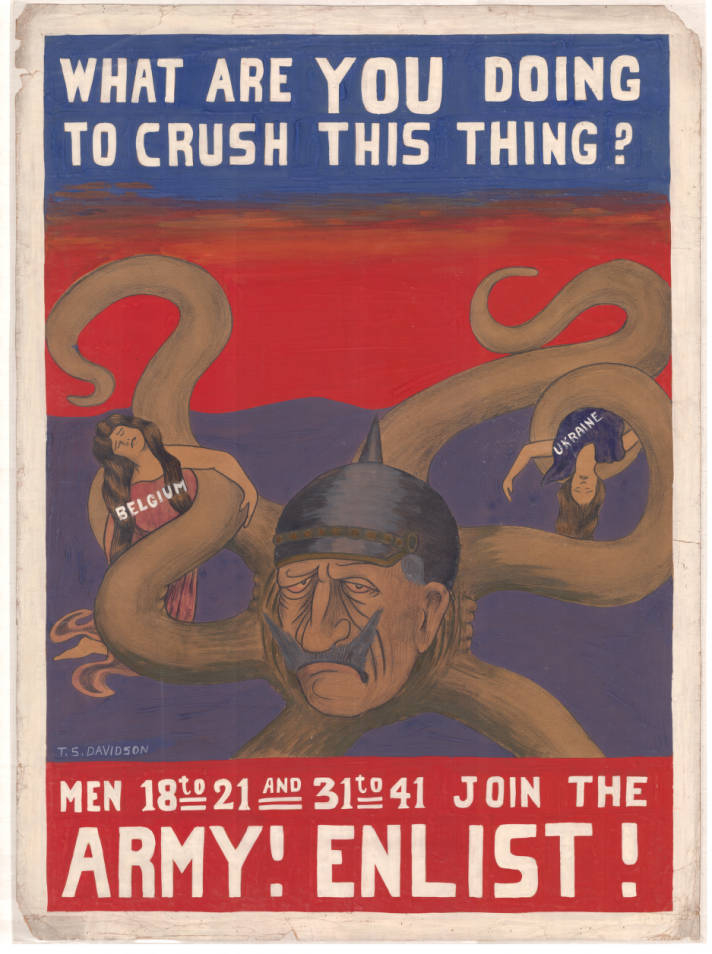

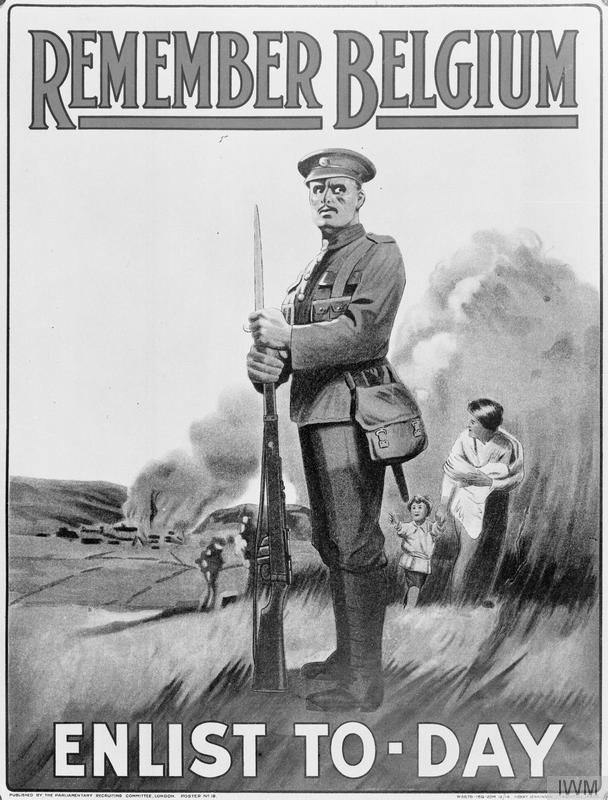

The invasion of Belgium was the foundation of the key propaganda tool for the Entente Cordiale, a Franco-British-Russia alliance created in August 1914.

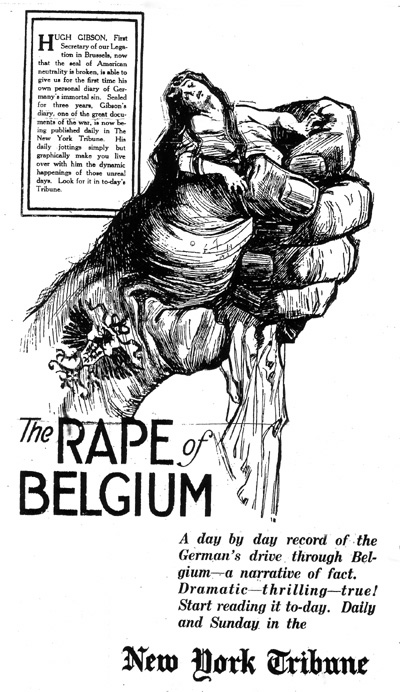

After Britain declared war on Germany for violating Belgium's neutrality (guaranteed by an 1839 treaty), British authorities spearheaded a propaganda push to muster anti-German sentiment. Detailed – and at times exaggerated – tales and cartoons of German atrocities filled international newspapers.

Britain played a decisive role in elevating the atrocities to galvanise its own population behind the war effort. Furthermore, the propaganda push also served to bring the US onside. America would not enter the war until 1917.

Early in the war, British propagandists were keen to move away from the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand to present a picture of "Poor Little Belgium" at the helm of an "army of jack-the-rippers," as Franco-British author William Le Queux described it at the time.

Stories were published in the press of German soldiers parading babies impaled on their bayonets, women being raped and mutilated and a particular story of a Canadian soldier being crucified. Historian Nicoletta Gullace argued that "the invasion of Belgium, with its very real suffering, was nevertheless represented in a highly stylised way that dwelt on perverse sexual acts, lurid mutilations, and graphic accounts of child abuse of often dubious veracity."

This is not to say that atrocities did not happen. The Bryce Commission, charged by the British government with investigating the issue, interviewed refugees who painstakingly related their accounts. During the invasion, German soldiers were ordered to keep daily diaries which would be later discovered by British forces after capturing German trenches, which also confirmed the veracity of many of the claims.

First World War Propaganda Poster. Credit: Imperial War Museum

"The force of the evidence is cumulative… If any further confirmation had been needed, we found it in the diaries in which German officers and private soldiers have recorded incidents just such as those to which the Belgian witnesses depose," the report read.

An entry in one of the diaries says: "We crossed the Belgian frontier on 15 August 1914 at 11:50 in the forenoon, and then we went steadily along the main road till we got into Belgium. Hardly were we there when we had a horrible sight. Houses were burnt down, the inhabitants chased away and some of them shot. Not one of the hundreds of houses was spared. Everything was plundered and burnt. Hardly had we passed through this large village before the next village was burnt, and so it went on continuously."

"Today in History" is a historical series brought to you by The Brussels Times, aiming to take you on a trip down memory lane for newcomers and Belgians alike, written and compiled by Ugo Realfonzo & Maïthé Chini.