A new study published in the journal Science Advances challenges the claim proposed by linguists that languages spoken by many non-native speakers (like English, for example) evolved to have simpler grammar.

In fairness to linguists — the claim sounds logical. If so many people are able to learn a language, then that language cannot be too hard to learn, right?

Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, however, concluded that the number of non-native speakers speaking a language is not associated with the simplicity of said language.

Thus, it also cannot have caused the grammar to evolve into a simpler form.

The Study

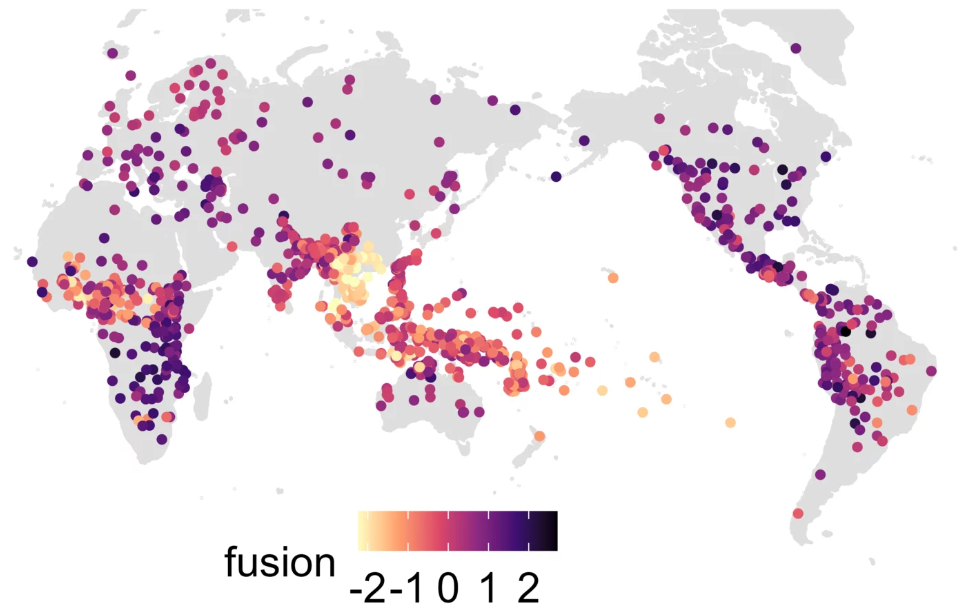

Researchers studied 1,313 languages with data from the new global grammar database Grambank. Though linguistic complexity is a highly contested topic, the research defined complexity by the number of distinctions that exist (informativity) and the number of affixes verbs and nouns used (fusion).

The global distribution of grammatical complexity (fusion). Closely related languages resemble each other’s scores. Credit: Olena Shcherbakova et al., Science Advances

The example provided in the press release is particularly clear: Swedish, Danish and Norwegian all use the word "hunden" for "dog" in sentences like "the dog is in the house" (dog is the subject), "someone found the dog" (dog is the object) and "someone gave food to the dog" (dog is the indirect object).

In English, for that matter, the same word for "dog" is used in all forms (nominative, accusative, and dative). Icelandic, however, has three different words depending on whether the dog is the subject, object, or indirect object, respectively: hundurinn, hundinn, and hundinum.

A misleading example

It does not take a linguist to realise that this makes Icelandic a complicated language. Still, some were quick to jump on the idea that "societies of intimates" like Iceland were able to develop more complex grammar thanks to their isolated communities and lack of foreigners.

In contrast, "societies of strangers" had to simplify their grammar to accommodate a large quantity of adult learners.

However, what the researchers found that the fact that English is more widely spoken as a second language than Icelandic, does not in real terms correlate with the complexity of the latter's grammar. English also did not develop simpler grammar as a result of its many non-native speakers. Whether it was the chicken or the egg that came first – neither is directly tied to the other.

"Our study reveals that the variation in grammatical complexity generally accumulates too slowly to adapt to the immediate environment," lead author Olena Shcherbakova added in the press release.

Related News

- Bilingual poetry market aims to showcase 'Belgium’s vibrant literary scene'

- Rue de la Loi, Wetstraat, Law Street? English may become Brussels' third official language

- Embrace 'bad English' as the European 'lingua franca,' says Timmermans

In fact, the counter-example that is commonly used in response to the Icelandic consideration is German, which has many non-native speakers and is still considered a complicated language by students and linguists alike.

There is more work to be done in the field of linguistic complexity, but another success of this study was to show how "linguistic wisdom can be rigorously tested with the global datasets that are increasingly becoming available," co-author Simon Greenhill concludes the institute's press release.