Yakoub Bouyahji left Syria for Belgium in 2015 as an undocumented migrant with a fake passport. Today, he’s a business engineer and Accenture consultant. If you crossed him on the street, you would never guess his past. But his climb up Belgium's social, academic and business ladders hides a dire journey.

Normality shattered

Bouyahji’s childhood in Aleppo was happy. But in 2012 a normal school day was interrupted by the sound of a huge explosion. The Syrian Civil War had hit Aleppo.

That was when the kidnappings and killings started. The bodies of the victims were tossed out onto the roads, especially a side road that Bouyahji took to go to swim lessons.

"For about one month, we would find a body on that road every day," he tells The Brussels Times. "And since our swim practices were early in the morning, we were always the first to call the police."

Then at 05:00 on a summer morning, Aleppo was overrun by rebels. The Bouyahji family locked themselves at home. When the fighting finally stopped, they tried to resume normal life. But when Yakoub returned to his swim classes he found the pool building had been pillaged.

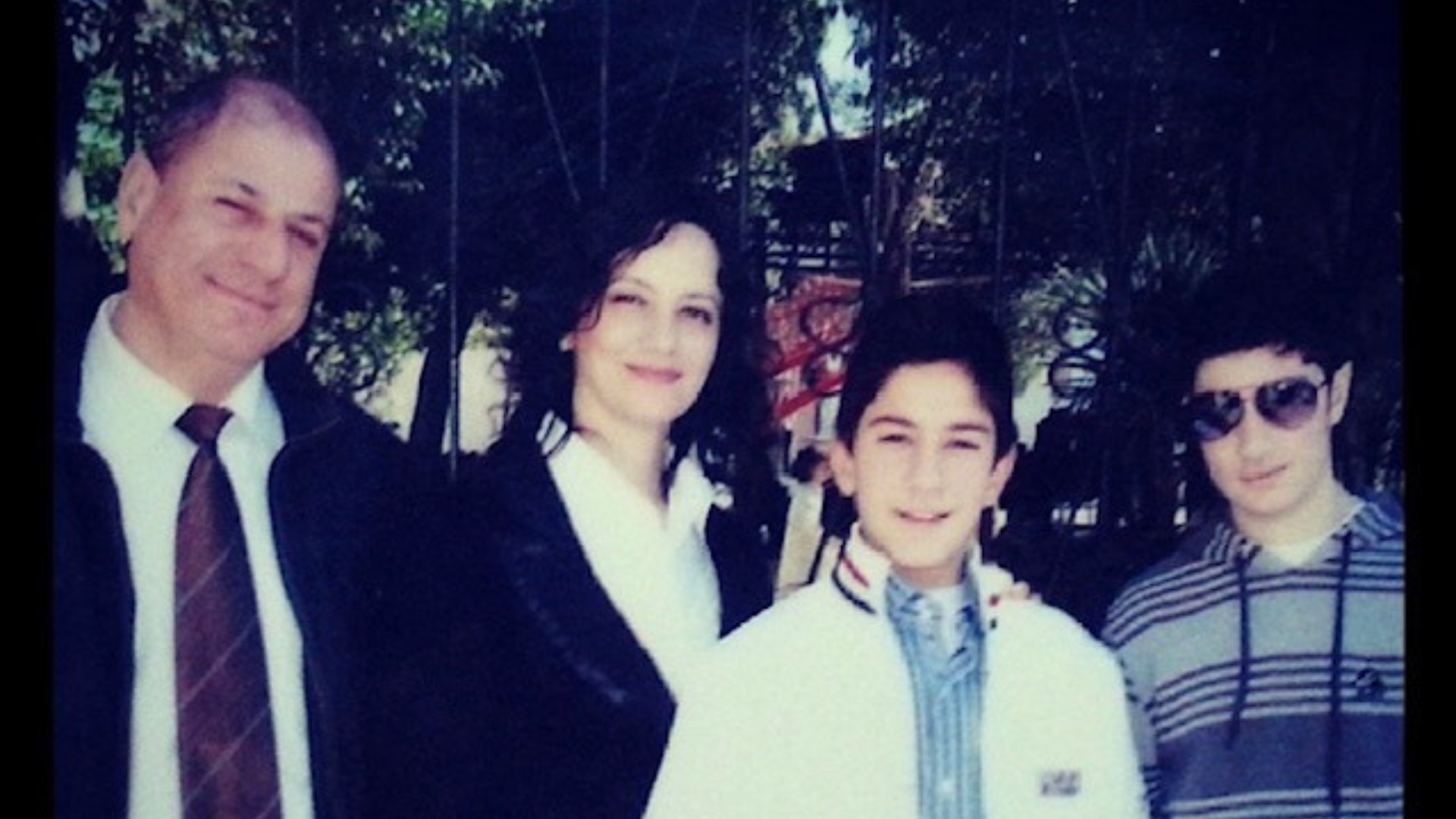

Bouyahji family picture in Syria in 2012, when the war arrived in Aleppo. Credit: Yacoub Bouyahji

Soon there was little water and electricity. Inflation began to raise the prices of goods and extremist groups that had infiltrated the then-proxy war moved in on Aleppo.

Bouyahji's maternal aunt lived in Belgium and begged them to leave for Europe. Bouyahji, his mother and some cousins and friends converted all their money into euros and booked a bus to Lebanon.

A clandestine journey

Before the war, the bus between Syria and Lebanon took about four hours. In April 2015 it took the Bouyahjis 34 hours – a journey of endless checkpoints. In Lebanon, they took a ferry to Turkey and then another 12-hour bus trip to Izmir (Turkey), where they met the smuggler who would get them to Greece.

"We'll give you as much money as you want, as long as it's a normal boat," his mother told the smuggler. The "normal boat" from Turkey to Greece cost them €2,000 per person. A week later, they went to the meeting point in the middle of the night and took another bus.

The bus drove through narrow mountain passes, and the road finally led down to the beach was impossibly narrow. One wrong turn could send the bus rolling over the edge.

"Everyone in the bus was screaming and shouting and panicking and praying," Bouyahji remembers. The driver pulled the hand break and let the bus slowly roll down the slope. They arrived on the beach, put their orange life jackets on and embarked the boat. The trip lasted five hours and was relatively uneventful. Once in Greece, the boat pulled up against the steep mountain and the passengers scrambled onto land. Someone then damaged the engine.

"To stay in Greece as a refugee you need to prove to the police that you arrived on the island unintentionally, that your boat stopped working. So the smugglers break the boat down after the journey as proof, so that the passengers are not sent back."

A hopeless liar

The Greek police quickly picked them up and brought them to the nearest station. Bouyahji's mother was the only one who spoke English out of the entire group of about 70 refugees. She had to translate for every one of them during the police interrogations. Part of the translation included convincing Muslim women to uncover their hair for the police to take their pictures.

Bouyahji (aged 15) in Simi, the Greek island where the smuggler sent Bouyahji and his family. One of the boats pictured behind him was the boat they used to arrive in Greece. Credit: Yacoub Bouyahji

The ordeal lasted three days, and the first night they had to sleep outside. Bouyahji was so cold that his mother pulled a blanket from a nearby house's clothesline. She returned it the next morning. Finally, on the third day, they received documents that would allow them to stay in Greece for six months.

In Athens, they paid a second smuggler €4,500 per person for passports and plane tickets to Brussels. It was difficult to find passports of a mother and son that matched their facial characteristics, but Bouyahji's mother refused to be separated from him. So the smuggler pasted their pictures onto stolen passports, and they hoped for the best.

At airports, there are generally three checks that refugees must pass, Bouyahji explains. The first is a visual one in which airport security look you up and down and pick out any "suspicious" individuals. The second is at security when anything with Arabic writing catches attention. The third and hardest is at the gate, where the flight crew scans your passport.

That was when Bouyahji and his mother were asked to step out of line. Bouyahji's mother gave him a French language book to keep him distracted. He was notoriously a bad liar and she worried he might accidentally give them away when a policewoman arrived.

The officer took their passports and asked them where they were from. "Belgium. You can see it right there on the passport," Bouyahji's mother replied. The policewoman tested the consistency of their passports, feeling the texture and flipping the pages. After a while, she let them pass.

'We made it'

Bouyahji would never know if the policewoman had really believed the fake passports. "When the plane took off, my mother started to cry. We'd made it."

In Belgium, they stayed with Bouyahji's aunt for a couple of days before registering at a refugee centre. They were sent to a Red Cross centre in the south of Belgium. Bouyahji recalls the time with surprising warmth. His family shared a bungalow with a couple from Sri Lanka with a newborn. Three months later, the Bouyahjis received a five-year residency permit. They moved to Brussels.

Finding housing in the city and a French language school for Bouyahji was more difficult than expected. But they were helped by social workers.

Left: Bouyahji with his mother and aunt after arriving at the Brussels airport. Centre: the life jacket Bouyahji's mother wore on the boat. Right: Bouyahji on the boat from Lebanon to Turkey. Credit: Yacoub Bouyahji

Bouyahji says he made friends quickly. His classmates were kind and approachable and he didn't suffer much culture shock beyond some funny moments in the cafeteria, like when his friends asked if his Syrian bread was a crêpe. Academically, the first year was hard, but it got easier. His father and brother were eventually able to join them in Belgium through a family reunification visa.

Bouyahji eventually got his bachelor's and master's degrees in business engineering. Today, he is a consultant at Accenture Belgium.

Individual fortune

Bouyahji's is a rare success story. It raises questions as to why the system worked for him while it continues to fail countless others.

Bouyahji is the first to point out that his family was privileged – they had the money to pursue “safe” migration options, while many others took plastic dinghies from Turkey to Greece and/or walked from Greece to Germany. As a war refugee in Belgium, Bouyahji feels he was given priority over economic refugees who Europeans believe "are coming just for social welfare.”

But he also thinks it came down to timing: "I came to Europe at the right time. In 2015 we had open borders, a lot of people were coming in easily and the process was efficient."

European borders are today far less permeable. The latest European elections – in which right-wing parties riding on anti-migration sentiment made big gains – say it all.

Bouyahji isn't surprised. With the Covid pandemic and then the war in Ukraine, EU economies – and their middle classes – have taken a massive hit. "It makes people angry. And angry people want to 'help our own before we help people from outside'. Most people don't consider that a migrant could have a degree and contribute to the economy.”

Bouyahji also points to increasing social tensions, exacerbated when isolated crimes are turned into national, ethnic or religious stereotypes. “I’m not surprised that migration policy in Belgium and in Europe has become less welcoming," Bouyahji concludes. But he’s ambiguous about the future: "Will this continue? I hope not."