When Marco Recchia moved to Belgium in 1957 to dig in Belgium’s coalmines, it was not his first time working the earth for black gold, as some called it.

He’d worked as a charcoal burner in the mountains of Campobasso in southern Italy, spending nights in the woods waiting for the fire to curl the felled trees into the hot black nuggets he could sell in town the next day. It wasn’t an ideal sleeping arrangement.

But it was easier than his new life in Belgium, where he would squeeze into an elevator cage, then crawl on his hands and knees through suffocatingly small coal veins barely illuminated by the oil lamp swinging from his neck. All in search of a different black gold.

And yet he never looked back. He never second-guessed his decision to emigrate from Italy, where his family was forever in want. “Something was always missing,” he says, rubbing the tips of his finger and thumb on both hands in the universal symbol for wealth. “There wasn’t any money. We never made it to the end of the year.”

Recchia, one of the last surviving Italian-Belgian miners, speaks in the Campobasso dialect and gestures with weathered but decisive hands as he sits at the kitchen table of his La Louvière home, not far from the mines he laboured in over six decades ago.

Now 95, he has told his stories many times. Old age has not diminished the deep pride that still shows in his shockingly blue eyes.

Recchia’s family was poor, as were all his neighbours. In the aftermath of the Second World War, Italy saw unemployment surge, especially in the south. Belgium, on the other hand, had lost its manual labour workforce with the repatriation of German prisoners of war and was looking abroad for replacements. The Belgians themselves had no intention of working in their own mines.

And so in 1946, Italy and Belgium signed the “men-for-coal” agreement, which did exactly what it sounds like: Italy would send men to work in Belgian mines in exchange for preferential rates on Belgian coal. It was a mutually beneficial solution that would fill Belgium’s working ranks, attract the unemployed and evict (at least from the perspective of the Christian democrat Italian governments) the communists and anarchists.

Government workers brandishing bright pink flyers began knocking on the doors of young men’s houses. They brought contracts that promised rapid accumulation of wealth, comfortable accommodations, the possibility to bring along the family and more.

As a result of this targeted campaign, the following ten years saw 110,000 Italians move to Belgium. Recchia immediately volunteered but was rejected after a mandatory medical exam in Milan diagnosed him with gastritis.

Marco Recchia today

Ten years after the signing of the men-for-coal agreement, at 8:10am on August 8, 1956, a misplaced wagon deep in the bowels of the earth in the Bois du Cazier mine in Marcinelle, Belgium, tore through an oil pipe, two high-voltage electrical cables and a compressed-air pipe. The damage ignited a fire whose poisonous smoke took 262 lives of the 274 that descended into the mine that morning. Some 136 of them were Italian, 95 were Belgian, along with some Poles, Greeks, Germans, Frenchmen and Hungarians. It would be the most catastrophic mining accident in Belgium’s history.

It’s grim up north

Recchia was in Switzerland when the Marcinelle tragedy pushed Italy to annul the men-for-coal deal. That meant that this time, he didn’t need to pass a medical test. He arrived in Belgium just a year later, when the victims’ families and the mining administration were still fighting it out in court.

He was aware – perhaps now more than ever – of the dangers of working in coal mines. But Recchia’s motivation was simple. “I wanted to get paid on Friday. It was for the family,” he says.

And so on August 24, 1957, Recchia descended into the Houssu mine in Haine-Saint-Paul for the first time with his brother and several friends. The elevator cage wasn’t big enough for them to stand straight: they had to crouch during the entire long and slow descent into darkness.

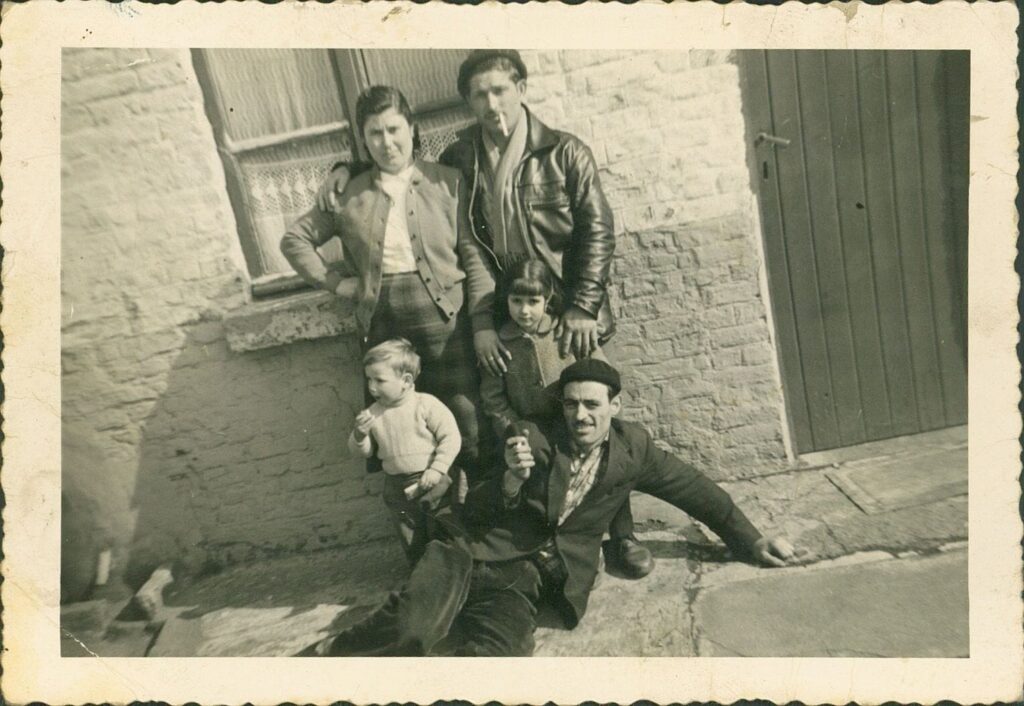

Marco Recchia, his wife Lucia, children Giovanna and Antonio and a friend around 1958

The mining tunnels themselves varied in size, from big enough to walk upright, to scarcely crawlable on hands and knees, to diagonal veins of coal only 50 to 60cm wide. Men shimmied up these spaces on their backs, and with barely enough room to breathe, would send the coal they dug out back down on pulley systems. Recchia said it was so hot they usually worked shirtless.

They could take a couple of minutes to eat lunch, and they drank cold black coffee from thermos flasks prepared in the morning.

However, the long hours of back-breaking work were rewarded by the salary Recchia collected every Friday. Making enough money to support his family was his only thought.

Still, it was never. Recchia would move many times during his mining career and beyond, following the work opportunities that promised better pay. In the beginning, he was paid a fixed daily rate of 200 francs to dig a set amount of coal, with extra pay for additional digging. He stayed in a small home with other miners, with two people per bed.

Italian miners arriving in Belgium

“I worked the day shift, he worked the night shift, and we shared the bed sheets,” Recchia remembers. But a shared bed was better than living in a converted prisoner camp, which is where most single men without families stayed when they arrived in Belgium.

Pride and prejudice

While many saw the Marcinelle tragedy as a wake-up call to improve working conditions in the mines, it remained the reality on the ground. Italy broke off the agreement, but Italians continued arriving in Belgium, where in addition to horrific working and living conditions, they faced continuous discrimination.

Recchia’s son Franco remembers spotting signs during his childhood outside of stores that read, “Prohibited to dogs and Italians.” The locals claimed the Italians were taking their jobs, though few would work in their own mines.

When it was time for Recchia’s wife and two daughters to join him in Belgium, he began looking for a house to rent. However, locals were not interested in renting their property to Italians. The only solution was renting a house from Italians who had immigrated to Belgium before the Second World War II – a house that, though no longer inhabited by the Recchia family, still stands today.

Recchia’s family finally arrived, and shortly after, their son Franco was born. The kids began attending Belgian schools. Recchia worked as hard as ever, putting in extra hours and chasing the highest paying mining shifts all over the country, including at Bois-du-Luc – which is now a heritage site like Bois du Cazier – commuting with any transportation available: bikes, busses, trams. “1,000 metres, 2,000 metres underground, it didn’t matter. It was for the family, always,” Recchia says steadfastly.

At one point he was earning 1,000 francs a day for a particularly dangerous job: setting the pit props, the supportive frames for newly dug tunnels to avoid collapse. Some of the parts of the frames weighed over 100kg and had to be carried up to two kilometres underground by foot.

The Marcinelle tragedy did prompt improvements in working conditions. Medical exams were introduced every six months, along with the use of masks to avoid breathing in silica (though their filters clogged up so quickly that miners usually removed them). The 4kg gas lamp that Recchia carried around his neck to illuminate the tunnels was switched out for a lighter oil lamp and then was eventually replaced altogether by a headlamp.

The funeral after the Bois du Cazier tragedy

During one of the medical exams, in August 1967, a doctor told Recchia that he could not continue mining: he had too much pollution in his lungs. He was 32 years old.

That diagnosis likely saved Recchia’s life. But it also put a father of four out of a job, with no compensation. The doctor suggested he file for unemployment.

“But we’re a family of six,” Recchia remembers protesting, “How will we manage?”

“As the others do,” the doctor, who worked for the mining administration, responded.

Recchia eventually went into construction work and then retired early from a back injury.

Keeping Italy alive

Others suffered worse than Recchia. After fighting in World War II, Ubaldo Noè left Le Marche in central Italy for Limburg in 1946 under the men-for-coal agreement. His wife, Anna Maria, joined him a few years later, and all four of their children, including Lorena Noè, were born in Belgium.

Lorena remembers the neighbourhoods built for miners and their families, where the Italian community was very tight knit. Her father’s generation started the Associazione Culturale Marchigiana del Limburgo, an association for Italians from Le Marche in Limburg, which acted as a middleman between Belgian bureaucracy and Italian immigrants, especially for those who had just arrived and didn’t speak French or Flemish. Things like helping mothers register their children for school and retirees receive their pensions from the government.

Group picture in an Italian miner neighborhood

The Marchigiana association also helped keep Italian culture alive by organising celebrations for Italian holidays like carnival, epiphany and Ferragosto. Lorena, who has headed the association since 2003, remembers the women in her neighbourhood cooking oven-baked pasta and stuffed olives for hundreds and hundreds of people, and parties in the Ardennes hills with card game tournaments, live music and dancing.

Women even volunteered to cook for and do the laundry of men who were either single or whose wives hadn’t followed them from Italy yet. “We were one big family,” Noè remembers. “There was solidarity among us Italians.”

But while the women did their best to keep their culture and heritage alive so far from home, the men were slowly dying.

Lorena remembers watching her father leave for the mine every day. All her friends’ fathers left every day, too. It was normal. Until one by one, they all started to fall sick. Then they all began to die.

Her father Ubaldo worked in the mines for 15 years. He became weaker and had trouble breathing. He was often hospitalised and kept an oxygen tank in the house.

Lorena remembers hearing him cough through the night and gasping for breath.

“It wasn’t easy for my siblings and me,” she admits. Their father was dying before their very eyes, in the care of blunt and unsympathetic healthcare workers. Ubaldo’s decline was accelerated by the shock of losing a friend and fellow miner whose equally intense coughing gave him a stroke.

Lorena’s father died when he was just 60 years old.

Many cases of silicosis were never recognised as work-related deaths, and so the families left behind did not receive any compensation for the loss of their husbands and fathers – and breadwinners. The only money they received was a meagre widow’s pension.

Like Recchia’s son, Lorena also faced discrimination in school. She remembers that as early as elementary school, teachers consistently paid more attention to Belgian girls – unless a punishment was in order.

Additionally, certain career paths and even certain schooling were only available to people with Belgian citizenship, which Lorena would have had to give up her Italian passport for. To this day she only has a Belgium residence permit, despite having been born and raised here.

Anne Morelli, Belgian historian and editor of the book ‘Retour sur Marcinelle’, argues that Marcinelle was not, in fact, a turning point in working rights for miners and that any progress made in that regard was thanks to the efforts of the miners themselves, their families and mining associations, like that of the Marchigiani.

Two wives, one family

Other descendants of Italian immigrants in Belgium returned to their Italian heritage in a more roundabout way.

Hervé Guerrisi, today a professional actor and translator, is originally from Calabria, in the southern tip of the Italian mainland. His grandmother Teresa followed her first husband, Luciano Cattareggia, to Belgium in 1948 along with their children, when no one had yet any idea what was waiting for them there. Her husband had arrived two years earlier, in the spring, though he remembers being greeted by a snowy landscape.

With the arrival of his family, Cattareggia was able to ask for a “real” house. Six months later, he died in a mining collapse.

“It wasn’t an exceptional occurrence. It happened every couple of days,” Guerrisi explains. “But unless there were three or more deaths in the same coal mine on the same day, work continued. These were the rules in Belgium in 1948.”

Widowed in a foreign country with young children to raise, Teresa called her parents in Calabria to ask for help. But she was the seventh of eight sisters, and her parents did not have the resources to take her and her children back in. “They said, ‘No, don’t come down. We don’t even have enough for ourselves. Try to figure it out there,’” Guerrisi says,

The wives and daughters of a commemoration

So after the passing of Cattareggia, Guerrisi’s grandmother remarried a friend and fellow miner of her first husband, Giuseppe Sollitto. The marriage was, from the beginning, one of convenience. With a wife and stepchildren, Sollitto could leave the housing for men, and with a husband working in the mines, Teresa got to stay in the house provided by the mining administration.

The marriage of convenience birthed Luciano, Guerrisi’s father. And then, a few years later, Teresa discovered that Sollitto had another family in Italy. Another wife and another son, who soon after joined them in Belgium, as well.

The two women considered each other, realised they had each done what they’d had to do, and then began cooking side by side. There wasn’t much else to do, after all, besides adapt to their shared experience of misery.

After six years wrought with problems of alcoholism, Sollitto died from silicosis. “There are many stories of alcoholism, of violence, of immigrant families desperately trying to manage the misery and the humiliation of working in the mines,” Guerrisi says. “Struggles that still exist in ‘modern’ immigrants, I might add.”

When Guerrisi’s step-uncle Luigi, the one who had arrived from Italy with Sollitto’s first wife, grew old enough to work in the mines himself, he stood at the mouth of the elevator shaft that lowered miners into the mine every day and said, “I’m not working there.” The next day he returned to Italy.

Guerrisi’s father Luciano was the only person in the family to go to university. He eventually married a Belgian woman and moved to Brussels, and in an attempt to integrate completely with his host country, he raised Guerrisi in French.

“He never wanted to speak Italian, certainly because he connected it to a painful experience. I mean, he called me Hervé, for goodness sake,” Guerrisi sighed. He says many Italians in Belgium of his generation have French names, not Italian ones.

Acting out black seam stories

Guerrisi was raised in Brussels and attended the academy of theatre at the Brussels Conservatory, where in his last year he worked on a text by Italian playwright Dario Fo about the sacrifice of Isaac. “The text entered me like it was part of my DNA. I don’t know how to explain it, but it was like a huge click, I felt myself represented in it.”

After graduating, he followed this call to rediscover his heritage in Milan and took an intensive Italian course. Afterwards, he called his father. “Ecco, papà. Parlo l’Italiano.” Look, Dad. I speak Italian, he told him over the phone. Guerrisi says his father was silent for a whole minute. He didn’t speak true Italian – he spoke the Calabrese dialect.

Guerrisi stayed in Italy and began working both as an actor and as a translator, which culminated in his translation and interpretation of Mario Perrotta’s production of Italiani Cìncali, a series of theatrical pieces dedicated to the stories of Italian immigrants abroad.

Hervé Guerrisi performing his immigrant stories

Guerrisi, naturally, acted in the piece about Italian immigrants in Belgium and even brought the performance to Marcinelle. “It was incredibly intense. I had a hard time finishing my sentences. There were ex-miners sitting in the front row with their intense gazes and arms crossed – but with pride, too. I was telling their story, after all,” he says.

After one of his performances, a particularly moved ex-miner approached Guerrisi and told him. “We suffered so much. Not like the immigrants of today, who arrive and are given housing and food and are treated like royalty. They are taking our jobs,” he claimed.

Guerrisi was shocked. The miner seemed to have forgotten that this was exactly what was said of Italians when they’d first arrived in Belgium. But Guerrisi also realised he had to do more. It was not enough to retell the stories of Italian immigration. He had to be more direct, more precise.

And so, in 2019 he and Grégory Carnoli, another grandchild of an Italian miner, created LUCA (Last Universal Common Ancestor), a theatrical exploration of inheritance, integration and most importantly, the timelessness of immigration.

“We must remember that we all come from a common ancestor – a common immigrant ancestor,” Guerrisi says. “Performing in Marcinelle was incredibly important, but what’s even more important is not closing ourselves around the story of a single community. I love it when my Italian family watches my LUCA performances, because they get it. They get that today’s immigrants are our grandfathers and our uncles.”

While Guerrisi says his performances are needed today to ensure the memory does not fade, his hope is that eventually it becomes obsolete. “I hope that people won’t have to be reminded that though we came by train and they come by boat, we have a shared experience of misery, like that between my grandmother and Sollitto’s first wife. But until then, we’ll continue telling the story – Marcinelle and LUCA – with love and joy, for as long as it takes.”