Nothing much happens in Mélin, a picturesque village of little over a thousand people about an hour’s drive from Brussels. If the sleepy town has a claim to fame, it is that many of its buildings – farmhouses, the church and the vicarage, the restaurant — are built from a chalky sandstone unique to the region.

The rock, which has been mined from local quarries since the sixteenth century, lends a cream hue to Gothic cathedrals across Belgium. There is no crime to speak of in Mélin. Cows flap their tails between hedgerows. Residents tend to their gardens and ride their bikes to the Saturday farmers’ market.

On a cold, drizzly Thursday afternoon in January 2016, two investigators from the federal police force in Brussels arrived in Mélin and pulled up to a redbrick house on the edge of town, across the street from a furrowed field. The “upscale villa in a rural village,” as the police later described it in court proceedings, was surrounded by metal fencing. The officers rang the buzzer and were let in through a pointed gate.

A petite, fine-featured woman with a ruby-red pixie cut and expressive eyebrows answered the door. Her name was Godelieve Soete, and though born in Belgium, she had spent much of her life in Africa. Her father had been a colonial police officer in the Belgian Congo, and decades later, after the colony’s independence, she herself had worked for Belgium’s embassy in the country. Now, at age 66, Soete lived a quiet life in Mélin, caring for her horses and her dogs, but she surrounded herself with reminders of her former home. Masks and spears adorned the walls. Cross-shaped ingots from the Congolese copper belt sat on the mantelpiece.

The police officers introduced themselves, flashed their badges, and presented a search warrant. Soete grumbled. She had been expecting this visit and was tired of the matter. The events under investigation had taken place when she was just 11, and they were her father’s doing, not hers. She knew that someone might show up at her door to punish her for his sins — hence the fencing and the electric gate.

Soete nonetheless gave the police what they were looking for. From a small blue wooden box, she produced a decaying molar capped with a gold crown. In another were a handful of spent bullets. The officers sealed the objects in a plastic bag and left for Brussels.

The tooth and the bullets were evidence in a cold case, an investigation into the murder of a man who had been shot to death in the Congo 55 years earlier, almost to the day.

Clerk, pitchman, prime minister

Patrice Lumumba did not last long in the limelight. A former postal clerk and beer pitchman in the Belgian Congo, he took the helm as prime minister when, on June 30, 1960, the Congo celebrated its newfound freedom from Belgium after 75 years of colonial rule.

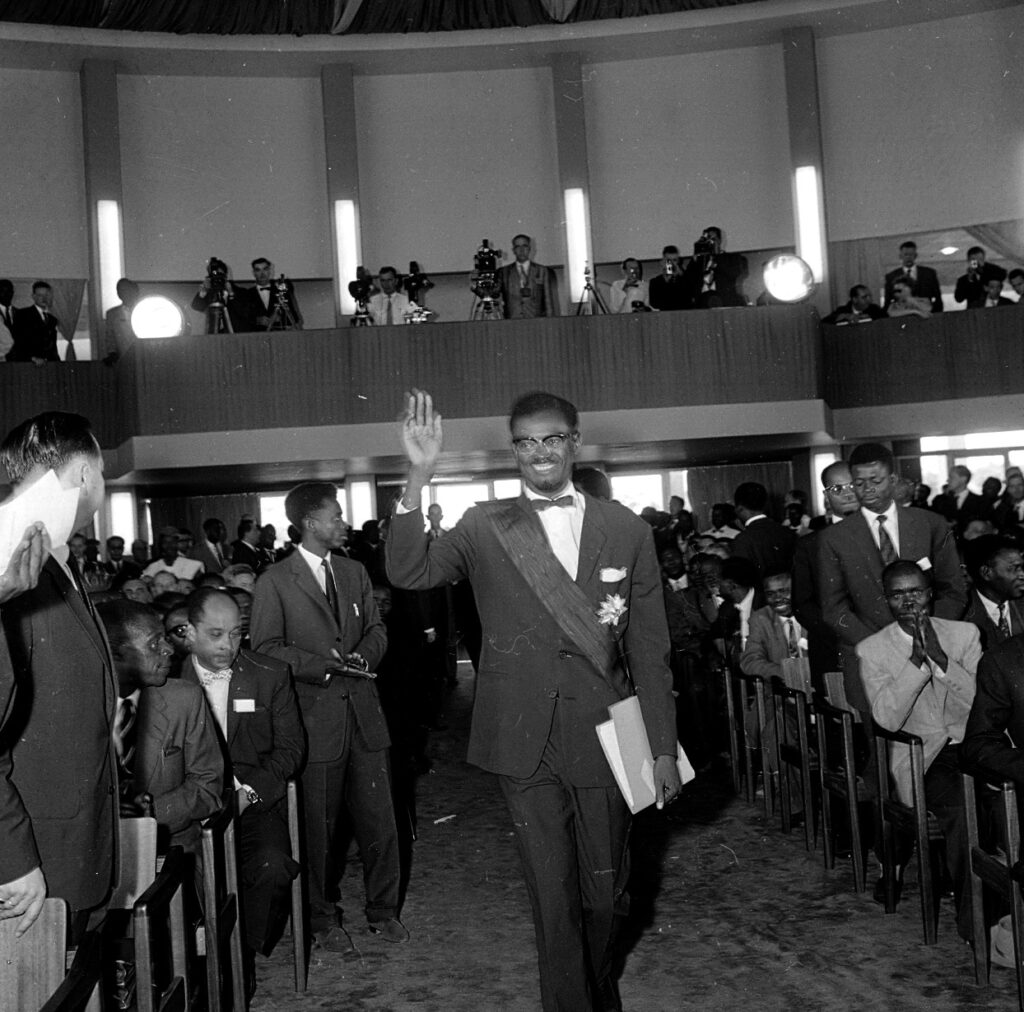

Patrice Emery Lumumba after giving a speech on 30 June 1960 in Leopoldville, Congo

Chaos engulfed the new country within days, forcing Lumumba to set aside his governing agenda and focus on survival. He quelled a mutiny in the army, invited in more than 10,000 United Nations peacekeepers, and toured nine world capitals to lobby for help that would save his fledgling nation. But after just two and a half months in office, he was ousted in a military coup. Four months later, he was assassinated. “He passed by like a meteor,” his daughter Juliana said.

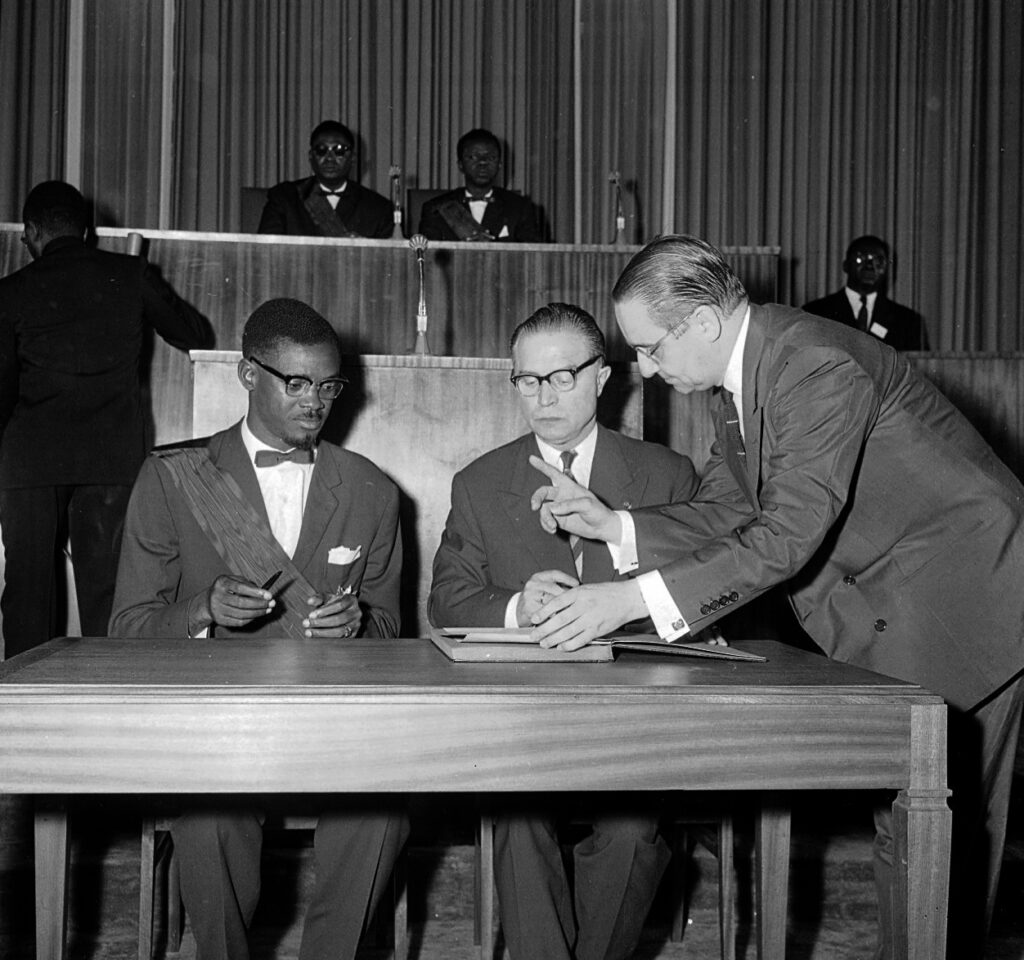

King Baudouin listens as Patrice Lumumba reads his speech on Independence Day

For decades, Lumumba’s murder remained a mystery. Debates raged over who bore the blame. Suspicion fell naturally on the Belgians, who had run their colony with unreserved cruelty before independence and bristled at Lumumba’s conception of national autonomy afterwards. Others pointed to UN officials, who were drawn into a peacekeeping operation of unprecedented scale and cost in the Congo and seemed to have a hand in his downfall and death.

Over the years, evidence came out suggesting that Lumumba’s suspected susceptibility to Communist manipulation had made him a target of the Central Intelligence Agency’s covert Cold War machinations in newly decolonized countries – and eventually, it was revealed that the CIA, acting on the orders of the White House, had dispatched vials of poison to the Congo in an effort to assassinate Lumumba.

But what ultimately became of the agency’s efforts? What about the man who deposed Lumumba and installed himself as leader, a young army colonel named Joseph Mobutu? And how exactly did Lumumba end up before a firing squad on the night of January 17, 1961, in a remote clearing in the Congolese countryside?

My book tries to at last answer these questions. Drawing on forgotten testimonies, interviews with participants, diaries, private letters, scholarly histories, official investigations, government archives, unearthed diplomatic cables, and recently declassified CIA files, it finds that the conventional narrative about the rise and fall of Lumumba leaves out much of the story.

I pay particular attention to the role played by the United States, laying bare the questionable motivations, unscrupulous methods, and grave damage of the country’s policies. My book shows how American officials privately displayed racist contempt for the Congolese. And it reveals that their involvement in the Congo was darker and more extensive than commonly thought and started earlier than has previously been known. The CIA and its station chief in the Congo, Larry Devlin, had a hand in nearly every major development leading up to Lumumba’s murder, from his fall from power to his forceful transfer into rebel-held territory on the day of his death.

Uncovering the truth about Lumumba’s downfall and murder – and assigning blame – matter not just in the name of Lumumba’s memory. For the Congo, the episode marked a turning point, the definitive end of a short-lived democratic experiment and the beginning of decades of poverty, dictatorship, and war. But the crisis reverberated far beyond the Congo.

It claimed the life of the UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld, killed under mysterious circumstances during a peace-making trip to the Congo months after Lumumba’s murder, and it permanently hobbled the organisation Hammarskjöld had led. The mission in the Congo came to be viewed as a dangerous misadventure, and the UN never fully recovered from the resulting damage to its global influence and reputation. No future Secretary-General would ever come close to equalling Hammarskjöld’s diplomatic heft.

The crisis in the Congo invigorated leaders in the United States, however. Extensive US meddling – carried out by CIA operatives and State Department officials – might not have looked so constructive in the streets of the Congo, but in the halls of power in Washington, it was seen as a smashing success.

As the Cold War intensified, America appeared to have stopped a Communist takeover in its tracks and, in Joseph Mobutu (who later called himself Mobutu Sese Seko), installed a friendly dictator keen on aligning with the Western bloc. While officials fretted about a supposed “missile gap” with the Soviets and the Communists’ inroads in Cuba, the Congo was a clear win. There was now a model to copy.

The American intervention in the Congo was an early battle in a decades-long series of covert actions that would showcase the conflict between interests and values in American statecraft. The relatively genteel strategies crafted by the so-called wise men of US foreign policy in the 1940s and 1950s gave way to the darker pursuits of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

Before America launched the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba, before it waded deeply into Vietnam, before it backed the Islamist mujahideen fighters in Afghanistan, before it illegally funded right-wing Nicaraguan militants in the Iran-Contra affair, there was the Congo.

It was in the Congo that the United States and the Soviet Union first faced off in a theatre far from either homeland, transforming the Cold War, until then first and foremost a European affair, into a truly global struggle. And it was in the Congo that the CIA, for the first and only time, could plausibly claim credit – or take the blame – for the assassination of a national leader. The United States still hasn’t kicked its habit of intense meddling in the politics of the developing world. That was a habit it picked up in earnest in the Congo.

The man behind the myth

Stories of armies, governments, agencies, and institutions have a way of obscuring the humans behind them. So it is with the post-independence turmoil in the Congo and Patrice Lumumba. With his murder, the man was lost and the myth replaced him.

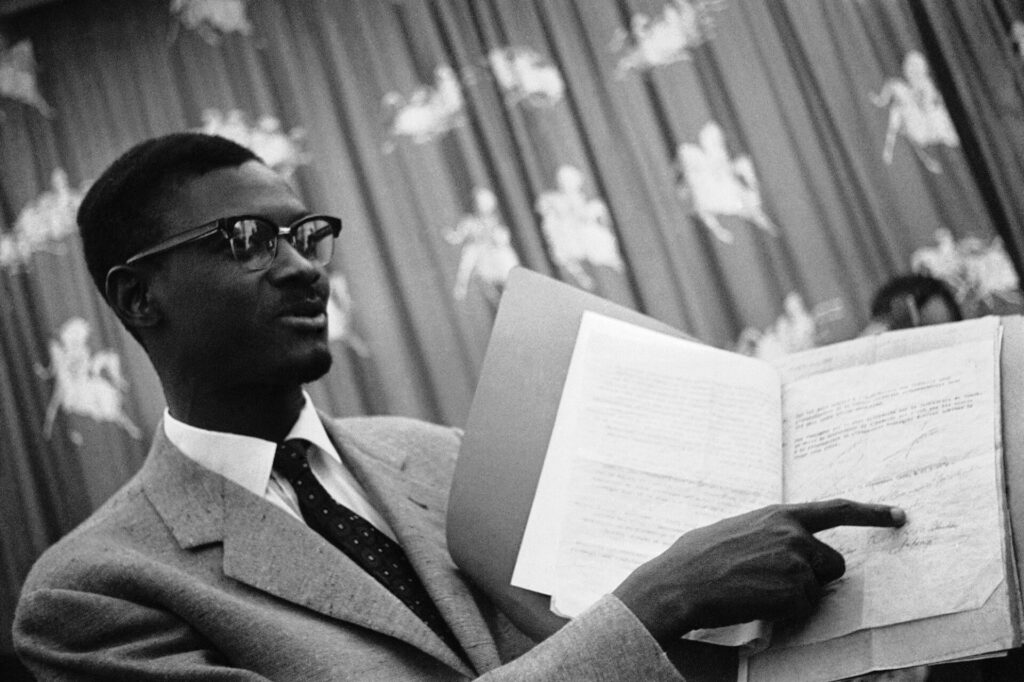

Lumumba at a press conference held in Leopoldville, Congo 20 September, 1960. It was his first press conference since his alleged arrest, Lumumba is showing the agreement he said had been signed between himself and President Joseph Kasavubu on September 17th.

The French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre wrote a fulsome introduction to a book collecting his speeches. The Soviet Union named a university after him. Congolese still wear wraps and T-shirts bearing his face. Depending on whom you ask, Lumumba was an agent of chaos who deserved his fate, a hapless fool outmanoeuvred by more powerful forces, or a flawless hero cut down by imperial cruelty. Few can acknowledge that he was none of these things yet many other things.

My book seeks to exhume Lumumba, to scrape away the mounds of lies, mythology, and conspiracy that have accumulated around him over the decades. I try, as much as possible, to present the man in his own words, in the context of his time, and through the prism of his own experiences. Contrary to a common Western belief at the time, Lumumba was not pro-Communist in any sense of the term, nor was he, as a slightly more sophisticated critique had it, particularly vulnerable to Soviet influence.

In fact, all the available evidence suggests he harboured a greater affinity for the United States than he did for the Soviet Union. Nor, however, was Lumumba a naive victim of Western machinations, as left-wing historians sometimes suggest. Yes, he was subject to powerful forces he could not control – and some he could not even see – but he had more agency than many imagine. He made brilliant choices and confounding choices. He was his country’s greatest politician and perhaps its worst statesman.

Above all, Lumumba was the author of his own story. It is the story of a striver whose intellect and perseverance lifted him from humble circumstances into his country’s highest political office. It is the story of a man who wooed the most powerful nation on earth but ended up accidentally turning it against him.

It is the story of a fearful United States, its view clouded by racism and reductive Cold War thinking, lashing out against threats more imagined than real. It is, at base, a story of how a moment of unprecedented hope gave way to unrelenting tragedy. And it is a story that begins a century ago, in the small hut in the scrubby grasslands of Onalua in central Africa, where he was born.