This year marked the centenary of the birth of the modern Republic of Turkey. The celebrations were ushered in with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan keen to mark his legacy following his surprise election victory in May, which extended his rule for a third decade.

On the day following the conclusion of the general and presidential elections in Turkey, Erdogan's victory was celebrated in front of a particular grocery store in Schaarbeek, Brussels. The jubilant crowd united in their chants for the President.

The proprietors of this store are well-known figures, being the uncle and aunt of Mahinur Özdemir, a Turkish-Belgian politician who previously held the position of a Member of Parliament in the Brussels-Capital Region before moving back to Turkey to serve as the Minister of Family and Social Services in Erdogan's government.

But the day after the jubilations, the local authorities paid an unexpected visit to launch a rigorous investigation into the store's operations, accompanied by substantial fines. Aunt Ayşe Özdemir related the difficulties that she and her husband have faced in Belgium due to their open support for Erdogan's Justice and Development Party (AKP).

"After the elections, celebrations took place right in front of our shop. Everyone here knows us. The very next day, local officials came to inspect the market and imposed fines." She explains that in the months following the elections have been filled with such inspections, accompanied by threats that the shop will be shut down. "The opposition keeps making complaints, I’m sure of it."

The elections and voting in Brussels

In the week leading up to what was described as the most pivotal election in modern Turkish history, thousands of Turkish nationals gathered at the Brussels Expo Center in Heysel. Billed as the "election of the century", Turkish expatriates, as well as those born and raised in Belgium, had the opportunity to cast their votes.

Hundreds of volunteers were on hand to ensure the safety of the ballots but tensions were high and some incidents broke out, some requiring police intervention.

The election signified the culmination of a protracted era in Turkish politics, poised to usher in a transformative period affecting everything from the nation's economic landscape to its path toward European Union membership.

Many voters were not even born in 2001, when the Justice and Development Party (AKP) and its leader, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, boldly challenged the long-standing Kemalist secular system and ultimately asserting themselves as the dominant force in Turkish politics. Yet this time, observers increasingly expressed optimism that the election would be different, ushering in the downfall of the AKP.

Turks living in Belgium waiting in line to vote for the Turkish elections. Credit: Belga

Since its inception, the AKP has consistently articulated bold and precise objectives for the nation's future, collectively referred to as "The 2023 Objectives," coinciding with the centenary of the republic.

These objectives encompass a wide-ranging vision: to position Turkey among the top 10 largest economies globally, elevate GDP per capita to exceed $20,000, foster a fully operational democracy characterised by the rule of law and the absolute impartiality of the judiciary, maintain unwavering commitment to the European Union accession process, among other objectives.

However, left with the reality of these unfulfilled objectives, Turkey’s stark economic challenges, record levels of debt, soaring inflation rates, high unemployment figures, and the looming spectre of potential expulsion from the Council of Europe, surely the Turkish people - including the Turkish diaspora - would vote for change.

Voting results by Turks abroad

Nationwide results in Turkey:

Recep Tayyip Erdogan: 52.18%

Results in Major European Countries for Erdogan (Where Most Turkish Citizens Reside):

- Belgium: 72.3%

- Austria: 71.9%

- Netherlands: 68.4%

- Germany: 65.4%

- France: 64.7%

- Luxembourg: 59.2%

- Denmark: 58.2%

- Norway: 52.45%

- Sweden: 44.2%

European Countries Where Erdogan's Support Was Relatively Lower:

- Bulgaria: 24.3%

- Italy: 23.9%

- Finland: 23.2%

- Hungary: 20.7%

- United Kingdom: 18.25%

- Greece: 16.8%

- Spain: 16.1%

- Lithuania: 11.7%

- Poland: 8.6%

- Czech Republic: 7.7%

- Portugal: 4.42%

- Estonia: 3.8%

*Participation abroad exceeded 53 percent, reaching the highest level since the 2011 elections. Overall, Erdogan received 57,5% of all votes.

Yet, in Heysel, and all the other election polls in Belgium, 72,3% of the Turkish electorate eventually casted their votes in favour of Erdogan and his ultra-nationalist alliance made up of other smaller Islamist parties. The same trend was observed in Germany, France, the Netherlands, and numerous other European nations, with notable exceptions in the United Kingdom and the United States.

So what motivated this overwhelming majority to sustain their unwavering allegiance to Erdogan and his political faction?

The integration that never happened?

The majority of the Turkish diaspora residing in Europe leans toward the right side of the political spectrum.

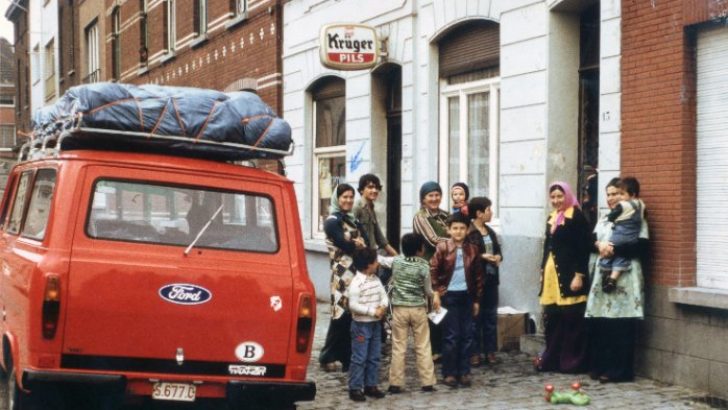

Many who arrived in the 1950-60s primarily originated from rural areas and small towns characterised by traditional lifestyles. Consequently, they transported with them a set of conservative, nationalist, and religious norms and values.

Concentrated in specific regions such as Schaerbeek in Brussels, Borinage in Mons, as well as Limburg, Ghent, Charleroi, among others, they fostered a sense of familiarity and solidarity within these self-contained enclaves, fostering a 'time capsule' effect.

As the decades passed, they remained insulated within these communities, with their mindset firmly rooted in the era they had left behind in their homeland.

"No, they haven't integrated sufficiently," says Cafer Yıldırımer, a Turkish journalist and the editor of the 'Yeni Vatan' (New Homeland) news portal, who was born and raised in Belgium. He offers a candid response when questioned about the level of integration among the Turkish community in Belgium. "I often face criticism for expressing this viewpoint, but it remains a reality."

"Six decades have elapsed since our arrival here, yet certain aspects have seen little transformation," says Yıldırımer. This lack of integration resulted in the perpetuation of these entrenched cultural and ideological right-wing viewpoints by the first and second generations.

"If you were to ask a random Turk in Schaarbeek, they would say: Of course, we've integrated. However, what they typically mean by this is; owning a home or two, establishing businesses, and cultivating a network of friends and family," he says.

"Even now, as the third and fourth generations emerge, insufficient time has elapsed for these values to undergo significant transformation. Most of them do not bother to acquaint themselves with the name of the current prime minister or comprehend the cultural and intellectual underpinnings of how things operate in this society," he explains.

Some elder figures from those initial generations still serve as role models within their families. "True integration necessitates, above all, a shift in one's perspective. Regardless of their affluence and contentment in Belgium, they remain emotionally tethered to Turkey."

The unwanted ‘Gurbetçi’

The Turks’ initial migration to Europe left them feeling isolated and estranged from both their home country and its people.

They were frequently seen as mere financial contributors, with anticipations revolving around sending money back to aid those who remained in their homeland. This selfless gesture often went unnoticed and received little recognition or respect.

Turkish migration began in the 1960s following a bilateral agreement signed between Belgium and Turkey in 1964 to encourage 'guest workers'.

The term "gurbetçi" means expatriates in Turkish but carrying connotations of leading an opulent life in Europe, complete with fancy cars and pockets filled with foreign currencies – they often felt like outsiders in Europe. Conversely, in Turkey, they were seen as cash cows with peculiar accents and hairstyles.

From the diaspora's vantage point, it seemed that no one truly cared about them – feeling unwanted wherever they were.

Consequently, the diaspora faced accusations of neglecting the welfare of their fellow Turks back home. However, their experience of neglect ended with the emergence of Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Finally a ‘hami’

In Turkish culture, the term 'hami' carries profound cultural significance, often synonymous with concepts such as protector, guardian, shield, or sponsor. This is precisely how many members of the Turkish diaspora in Belgium and around the world perceive Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

The diaspora had long felt neglected and unsupported for many decades. However, a notable shift in policy occurred during the early years of Erdogan's leadership. Ambassadors were instructed to establish close communication and attentiveness to their concerns. Numerous practical and bureaucratic challenges were successfully addressed and streamlined.

A significant milestone was the removal of the mandatory long military service obligation for those residing abroad, a substantial relief for the diaspora.

Erdogan himself made history as the first leader to host separate rallies and large-scale meetings with the diaspora during official visits to foreign nations. The AKP leader connected with their sentiments and experiences, articulating how individuals like him had been marginalised in Turkey.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and King Philippe of Belgium during a state visit to Belgium. Credit: Belga

He frequently emphasised how their sons and daughters had been compelled to pursue education abroad in order to exercise their religious rights and freedoms, including the wearing of headscarves in educational institutions.

In addition to this, Turkish expats regarded Erdogan as a charismatic political figure unafraid to vocalise his robust opinions regarding Europe and its policies. Whenever Erdogan criticised Europe, it resonated with them, akin to their team scoring a point against the system that had long alienated them.

"As a predominantly Muslim country, Turkey should forge its unique path rather than solely pursuing the European route,” says Ömer Yıldız (56), a labour law expert and trade unionist as well as being prominent Erdogan supporter residing in Belgium. He is not hesitant to express his unwavering support for the Turkish leader.

"It's not that we are suggesting Turkey should refrain from pursuing European integration; instead, our perspective is rooted in the recognition that Europe, at its core, exhibits reluctance in embracing this notion. Therefore, I find it somewhat perplexing why Europeans harbour antipathy towards Erdogan," says Yıldız, who firmly believes in Erdogan's stance towards Europe.

All sunshine and rainbows

The media landscape in Turkey, which is predominantly influenced by the ruling elite, also holds significant sway over how the diaspora perceives developments within Turkey.

Yıldırımer highlights the disconnect, stating: "Many within the diaspora fail to grasp the issues plaguing Turkey." And he underscores the role of media and news content, remarking: "When you examine the advertisements, television series, newspapers, and channels, everything appears picture-perfect."

Turkey President Recep Tayyip Erdogan greets people at his arrival in Belgium, Monday 05 October 2015 at Place Stephanie. Credit: Belga

Indeed, things seem quite alright to many. Schaerbeek shop owner Ayşe Özdemir, who is the aunt of Mahinur Özdemir, a Turkish-Belgian politician who served as a member of parliament in Brussels and then became the Minister of Family and Social Services in Turkey.

With celebration outside her shop following Erdogan's win, Özdemir also narrates that she and her husband haven’t had it easy in Belgium due to their open support for the AKP.

Yet Özdemir suggests that Europeans quietly envy Turkey, but they rarely express it. She points out Turkey's well-maintained infrastructure, including roads and advanced healthcare facilities, implying that Europe may be losing some of its appeal, as many individuals are considering returning to Turkey from Europe.

"I visit Turkey several times a year, and it's clear that cafes and restaurants are always bustling. If the economy were in dire straits, we'd see fewer customers," says Ayşe regarding Turkey's economy and President Erdogan's leadership.

"Erdogan has provided significant social support, which may have unintentionally encouraged some people to become a bit complacent. We're aware of Erdogan's mistakes, but, in the end, he's been a strong advocate for our identity and pride in the European context. We will always support his leadership."

Like kings and queens

There exists a pragmatic dimension to this narrative. Just like the ‘time capsule’ effect, when it comes to voting whether in Belgium or elsewhere in European countries, there is another well documented phenomenon.

The Turkish diaspora, characterised by its 'right-wing political values,' almost always lends support to parties situated on the left end of the political spectrum in Belgium – socialists, liberals, greens...etc.

The reason being that progressive parties tend to advocate more favourable immigration and ethnic minority policies, while exhibiting greater tolerance towards different cultures. After all, European conservatism isn't aimed at preserving Turkish values and norms.

Belgian Prime Minister of the time Guy Verhofstadt welcomes Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the leader of the Turkish Justice and Development Party (AKP). Credit: Belga

Consequently, when the diaspora receives preferential treatment from European politicians, they experience a sense of economic and social superiority both in their adopted homeland and during visits to their country of origin.

From their perspective, when Erdogan's controversial economic policies result in the depreciation of the Turkish Lira, or when his track record on human rights and the rule of law deters foreign investment, they find themselves feeling even more affluent when returning to Turkey.

They become akin to monarchs, wielding their purchasing power with ease, affording themselves luxuries and comfort. Which makes them prefer this version of Turkey over another.

Yet, Erdogan supporters are reluctant to admit to it. Yıldız disagrees with this less rosy narrative, and instead points to high inflation, adding: "On the contrary, the Euro does not have the purchasing power as before. The price of everything has gone up which makes it expensive even for us."

An opposition that no longer opposes

In recent elections, many voters who harbour reservations about the Erdogan administration find themselves reluctant to cast their votes for the main opposition parties due to dissatisfaction with them.

"This so-called 'opposition' fails to meet our expectations," says Medyen Sever (50), an individual residing in Brussels since 2005.

"We have lost all faith in Turkish politics. According to people like me, these politicians do not meet the criteria of being 'serious' and 'realistic'. Thus, we express our frustration and anger in this manner. We seek change in Turkey, but that transformation must first commence within the ranks of the opposition."

Yıldız also contributes to this point by expressing what drives him to vote for Erdogan even when he feels disappointed and frustrated: "To be honest, there have been times I felt like stopping my support. But then again, who else was worthy to support?"