On this day, 3 December 1930, the death toll from a mysterious heavy fog in the Meuse Valley in Belgium rose to 64 people.

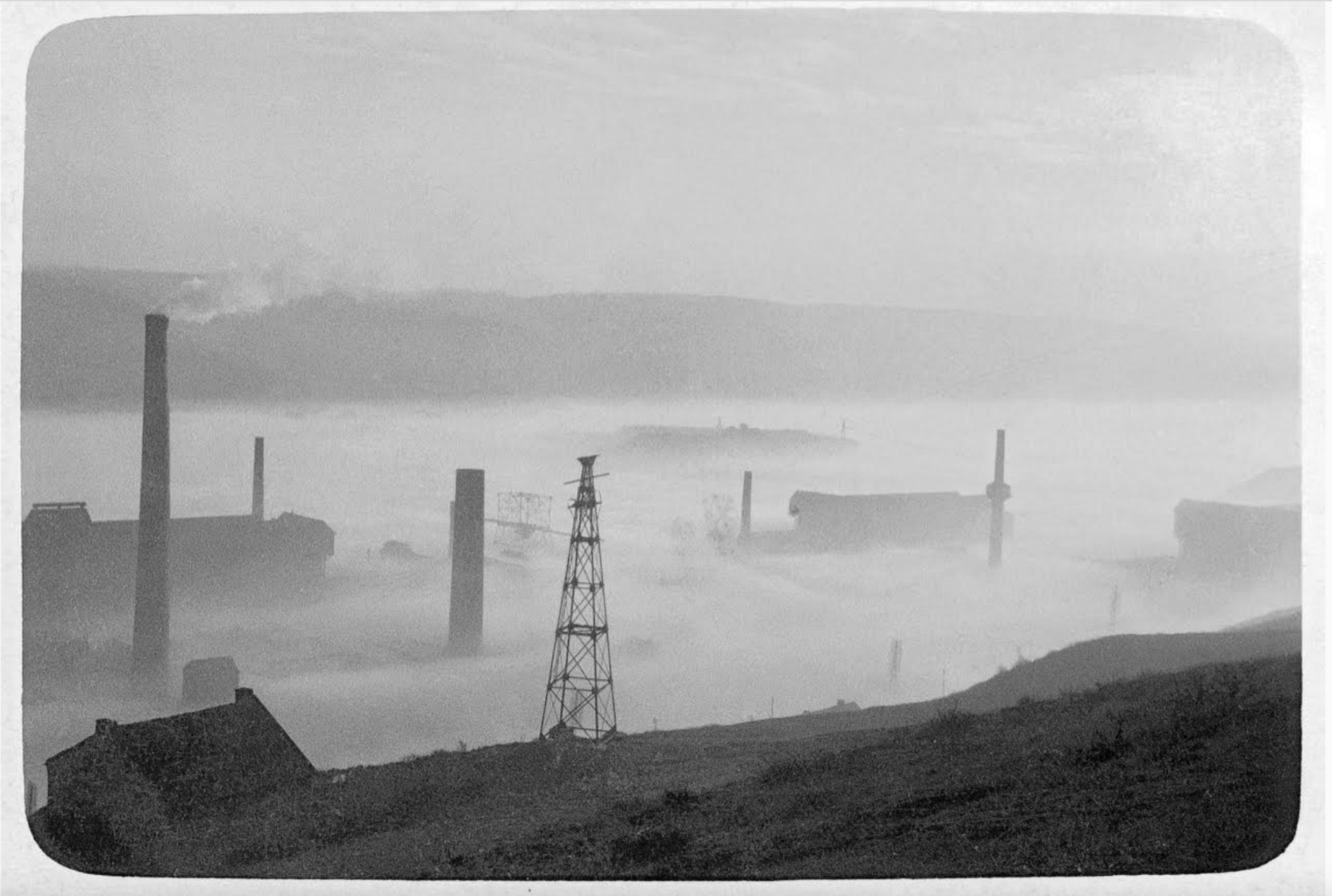

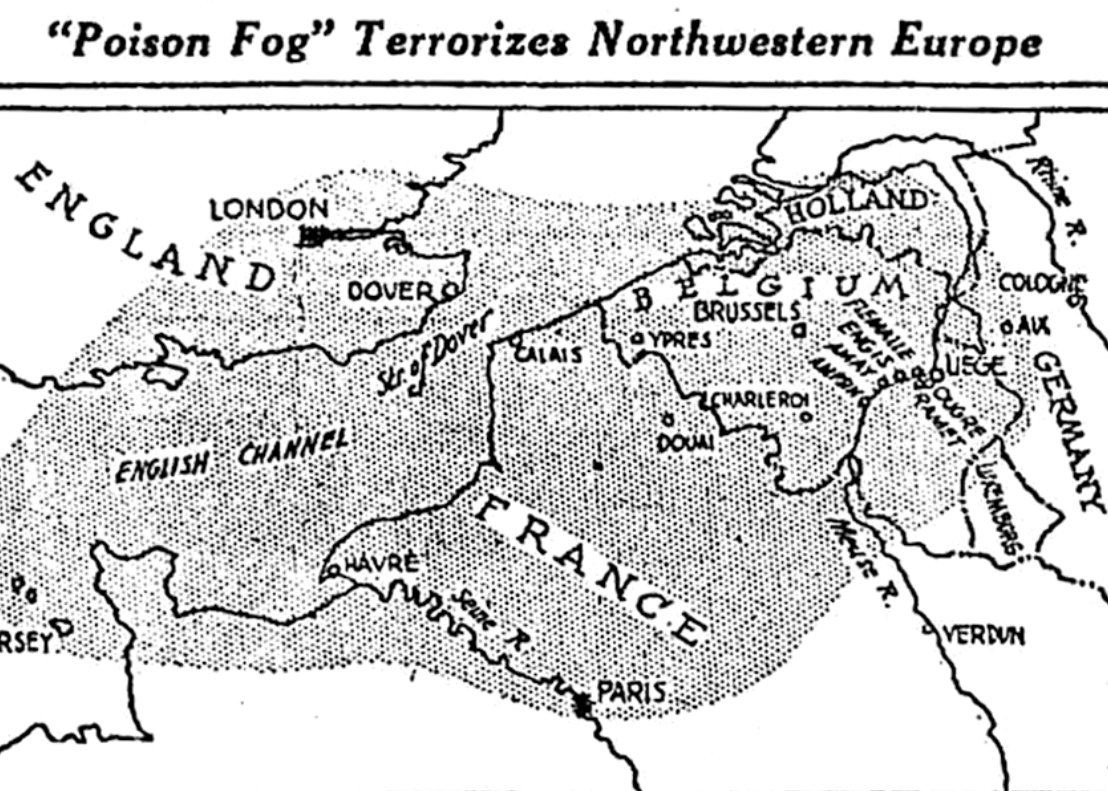

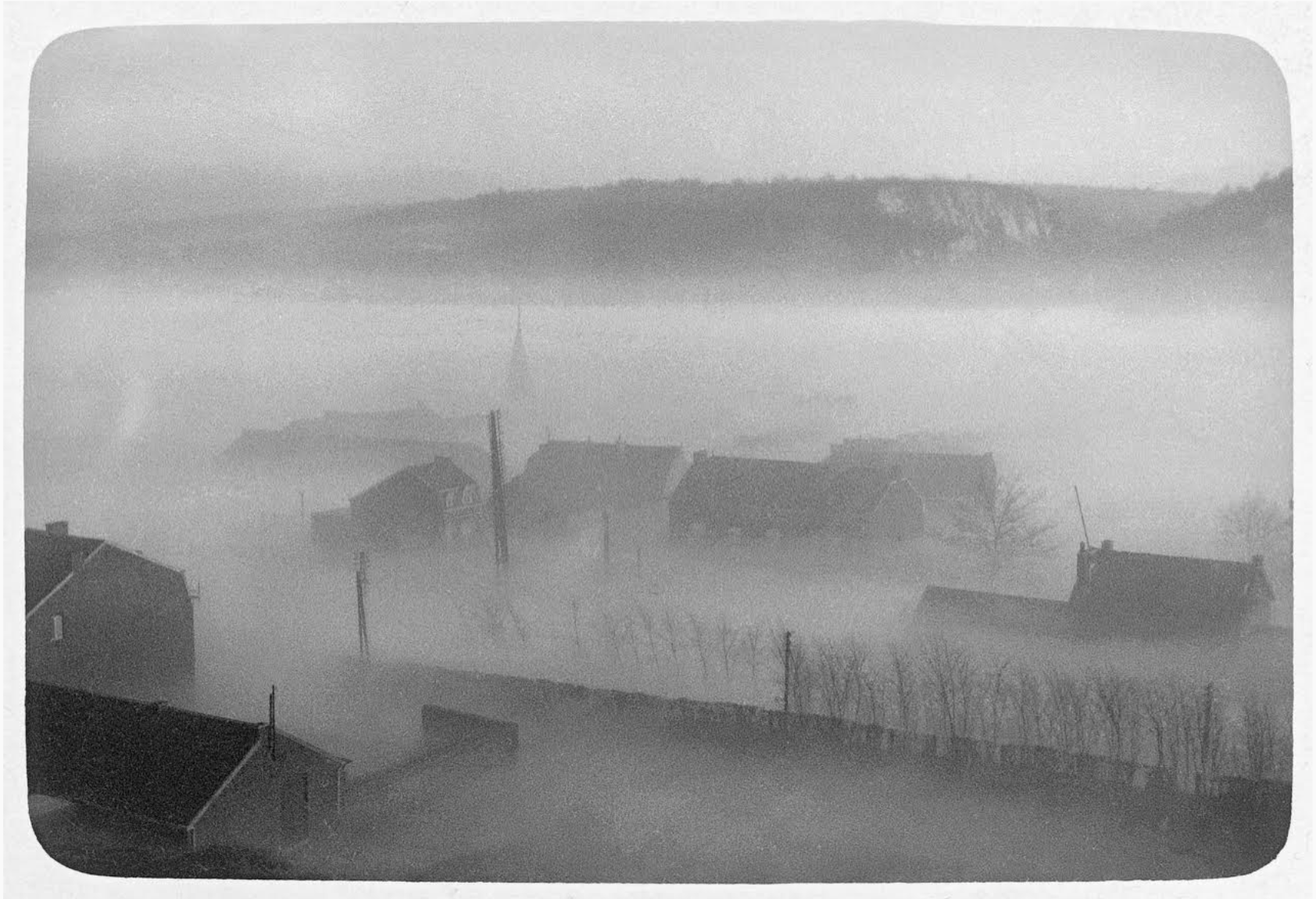

On a cold December morning, the Meuse Valley awoke to a heavy fog engulfing the entire country and large swathes of northern Europe. Ships, canals, trains and all other forms of transport were brought to a complete standstill.

Yet soon after the descent of the heavy mist, a respiratory illness struck the towns and inhabitants of the Meuse Valley. The illness puzzled residents, officials and even the Ministry of Health. Frenzied newspapers dubbed it a ‘black death’ while branding the area ‘the Valley of Death.'

The possibility of an external gas attack was even looked into; the Belgian Government quickly sent 20,000 gas masks to the area, with memories still fresh of the first-ever gas attacks in Belgium 15 years earlier during the Great War.

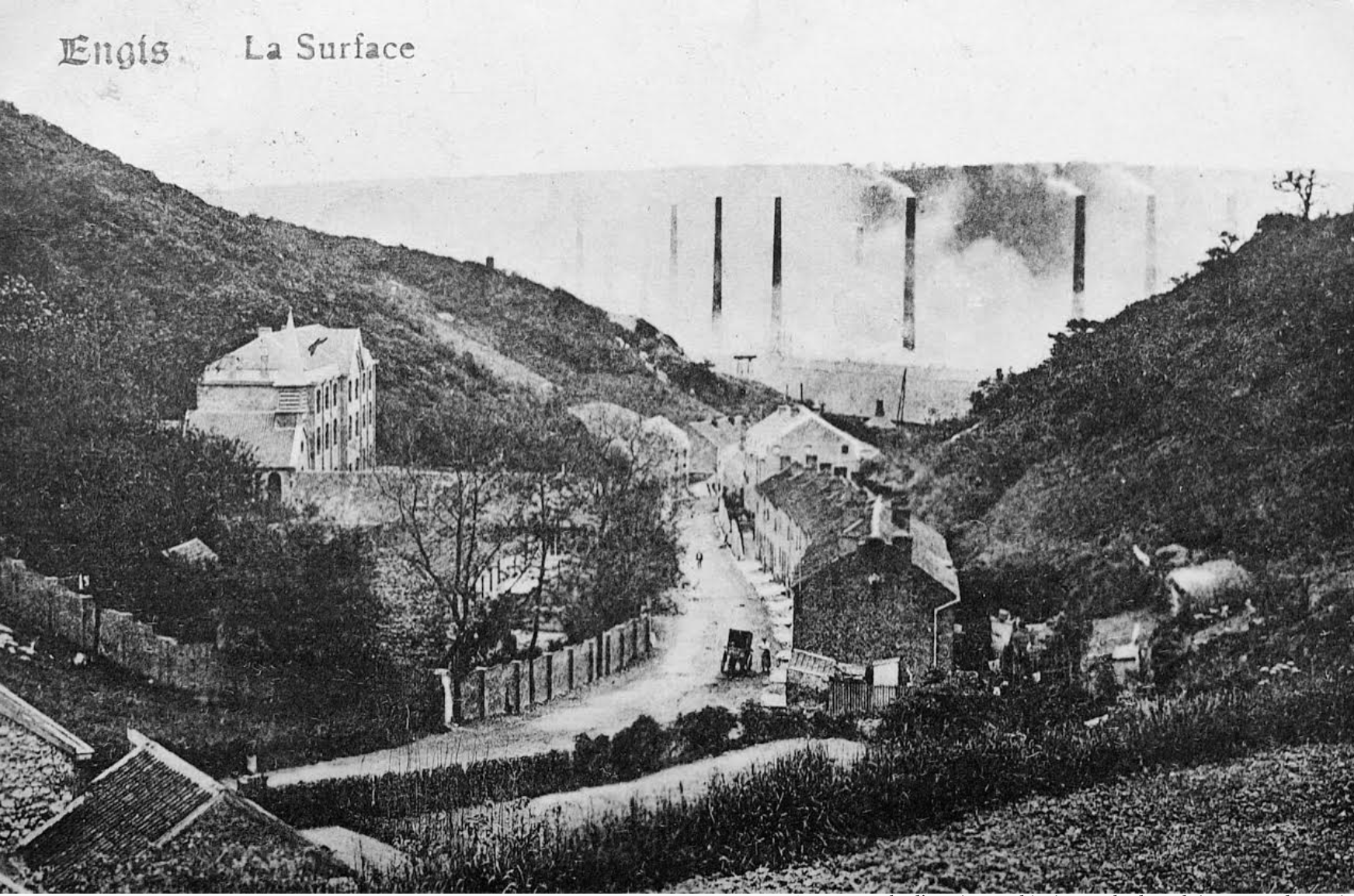

Located inside Wallonia's industrial heartlands, the Meuse Valley had many factories burning coal and producing zinc, steel, fertiliser, and explosives. Between Liège and Huy, there were 27 factories, all built around a densely populated area tucked inside a long valley which follows the river Meuse.

With complaints about industrial pollution in the area going back to the 19th century, the valley's conditions triggered the perfect toxic storm.

In those days, the atmosphere had suffered a temperature inversion, with lows hovering around 1 to 2°C and very light winds (1 to 3 km/h) blowing the accumulation of gases and soot particles through the valley.

A cocktail of condensed water and industrial dust made the fog particularly persistent. The conditions were also worsened when the presence of oily substances on the dust itself kept the particles of sulphur dioxide (SO2) suspended in the air – and was subsequently breathed in by humans and animals.

Credit: Albert Humblet collection.

The damage was immediate. Within three days, thousands of people in the Meuse Valley were suffering from respiratory problems, notably throat irritation, chest pains, coughing fits, difficulty breathing, increased adrenalin, nausea and vomiting.

Over 60 people suffering from heart or lung disease died in two days. Many of the victims were under 30 years old; the youngest one was only 20 years old and died while walking home from a party.

One of the worst hit areas was the town of Engis, which had already garnered a reputation as Belgium’s most polluted town, where 56 of the deaths happened.

After the fog

When the fog finally lifted, an inquiry was called on 6 December amid general confusion and anger. A committee of experts was sent to perform autopsies on the victims and collect air samples.

Initially, the Ministry of Health was informed that the sudden deaths in the Meuse Valley were solely caused by the fog and not due to any communicable disease. "The occurrence is clearly a matter of local conditions," the Ministry's press statement noted in the following days, "but it may be some days before the cause is fully and authoritatively ascertained."

On Saturday 13 December 1930, dissent was growing over the government's version of events, that fog alone had been the cause of the deaths. "The public are not all inclined to accept this explanation of their suffering and loss, and are convinced that the fog was charged with some noxious gas," various British newspapers reported that day.

At the time, the Mayor of Engis attributed the deaths to sulphuric acid fumes, which, owing to the static air and lower temperature, did not rise and mixed in with the heavy fog. For years, local authorities had been expressing concern over pollution levels emanating from nearby factories.

Engis. Credit: Académie royale de Belgique, Fonds Dexia.

During the autopsies, high levels of mucus were found in the victims' trachea and bronchi, which led to pulmonary oedema and haemorrhage, but no signs of systemic poisoning were found.

These findings were published in the Bulletin de l'Académie royale de médecine de Belgique in 1931.

Belgian historian Maxime Tondeur argues that this report was a landmark in the history of air pollution, as it was the first time that mortality and illness caused by air pollution had been scientifically demonstrated.

These findings made the noxious effects of fossil fuel-driven industrial pollution impossible for the authorities to deny for much longer. They identified the risks of combining winter fog, temperature inversion and the products of coal combustion as well, but also predicted future disasters.

The report claimed that if such a phenomenon were to grip a city like London, there would have been over 3,000 deaths. And indeed, the Great Smog Of London in 1952 killed around 12,000 people, according to modern estimates.

Queen Elisabeth visits the town of Engis after the disaster.

After the disaster, the Meuse Valley factories were never held liable for the deaths. The authorities sustained that the presence of deadly sulphuric acid in the atmosphere was down to a chain of unfortunate events and rare climate phenomena.

But the disaster still had a major impact on the scientific community, and Engis would later become one of the most closely monitored municipalities for pollution. Yet 97 years later, Belgium still ranks poorly in air quality indexes. As the PFAS water scandal in the last month has shown, Belgians are still today at the behest of industrial waste.

"Today in History" is a historical series brought to you by The Brussels Times, aiming to take you on a trip down memory lane for newcomers and Belgians alike, written and compiled by Ugo Realfonzo & Maïthé Chini. With thanks to Maxime Tondeur.