More potatoes? Only once you have eaten all of your sprouts! is the perennial battle cry of parents heard at Christmas dinner tables whenever Brussels sprouts are involved.

Love it or hate it, the Brussels sprout is a popular vegetable which emerged from the colder climates of Northern Europe, and more precisely from the rural hills just outside the Brussels city walls.

After taking Europe by storm, the boiled Brussels sprout remains today an essential component of the United Kingdom’s Christmas day meal – much to the sustained suffering of generations of British children who often complain about the bitter taste.

However, the controversial small green cabbage – often seen as part of a roast dinner – did not originate from the City of Brussels but just outside the city walls in the nearby Saint-Gilles.

In the past, and particularly before the creation of Belgium, Saint-Gilles was a rural area with fields, mills, farms and a fort.

While the ancestors of the current Brussels sprouts are believed to have had Roman origins, the cultivation of cabbages and sprouts in Saint-Gilles is said to go back as far as the 13th century.

The Brussels Sprotje was the result of the innovation of cultivation methods pioneered in Saint-Gilles and enacted as a response to the quick urbanisation of Brussels.

Around 1550, the area began to grow a variety of vegetables, especially cabbage, as a result of the rapid increase in the population of Brussels. The production thrived in colder climates (7°C to 23°C), with the area becoming known for its cereals and cultivation of market crops, particularly cabbages.

The area's production was boosted by water mills and a stream which used to run down the hill – starting from today's Albert by Forest Park, past the town hall of Saint Gilles and the Barrière to where Rue de France is today.

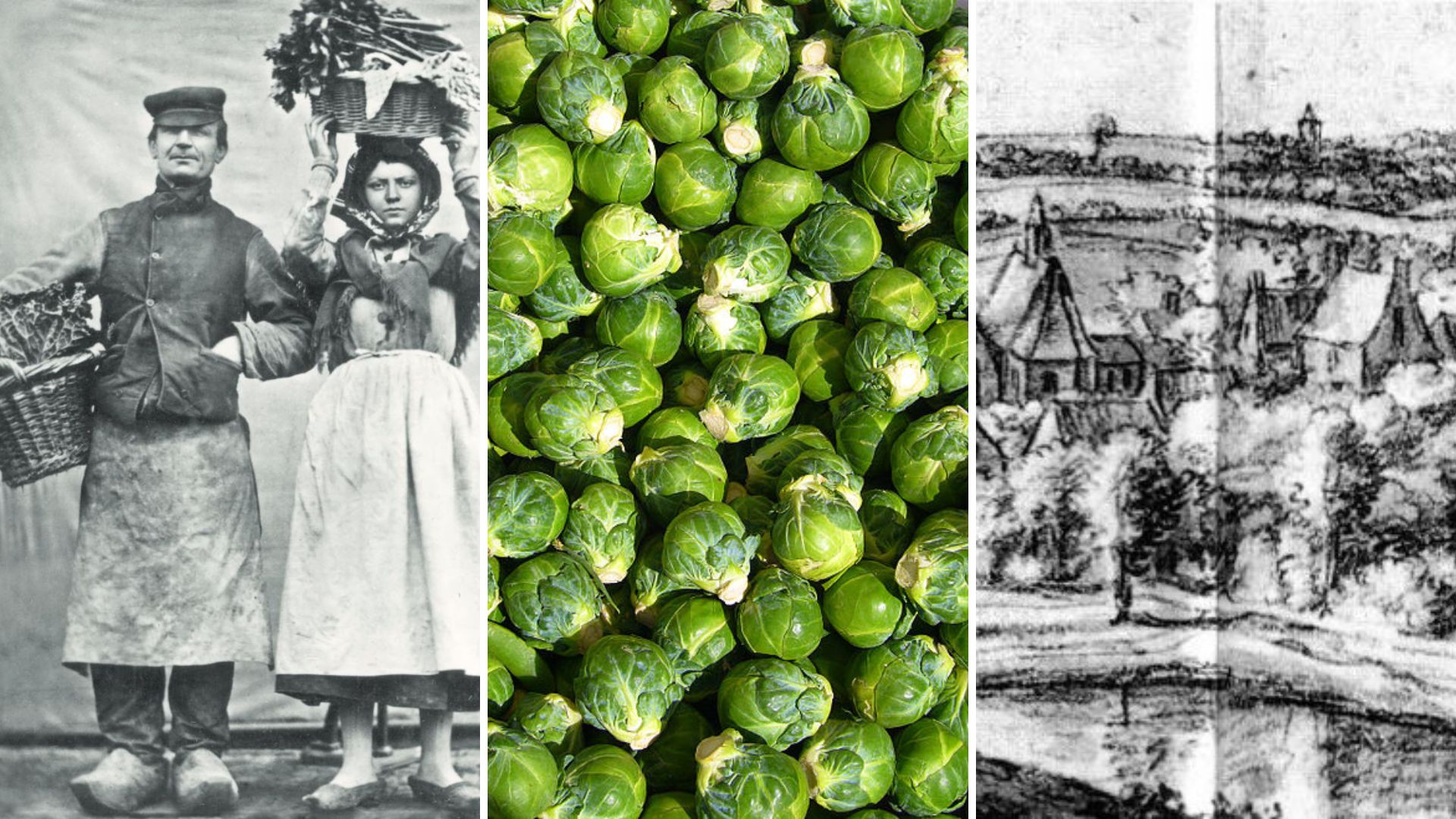

Tool engraving by Hans Collaert (1566-1628) based on a painting by Hans Bols, towards 1560.

To keep up with demand, the Saint-Gillois growers created a new cabbage hybrid in 1685, which was cultivated vertically. In this way, growers maximised precious cultivable area which was becoming scarce with the increasing population. As the method ensured a high yield, the practice proved very profitable.

The men and women of Obbrussel – as Saint-Gilles was known until the end of the 18th century – would carry their cultivated crops through the Porte de Hal and sell their produce at Brussels' many markets. Others would sell it locally: the market of the Parvis de Saint-Gilles is a legacy of when Saint-Gilloise women would go to the market to sell their vegetables.

The village was so strongly associated with growing vegetables that they earned the affectionate nickname of kuulkappers (cabbage cutters).

Sprouts expanded to neighbouring countries, and proved extremely popular – it was the French who coined its name: Choux de Bruxelles. They became hugely popular in Britain during the 19th century. Some sources suggest they first landed on market stalls in the 1880s, but British newspaper records cite Brussels sprouts as early as 1810.

The legacy of market gardens in Saint-Gilles was crucial to the development of the sprout. In 1841, 92% of Saint-Gilles was covered by market gardens and meadows, but by 1873, only 41 farmers remained – less than 5% of the population. Indeed, the last sprout field only disappeared from Saint-Gilles in the 20th century.

Chaussée de Forest towards 1910, at the location of the Church of Jesus the Worker. In the background, facades in rue du Monténégro. Credit: KBR

A guild was established in 1985 by the kuulkappers' descendants to preserve Saint-Gilles' sprout heritage and culture. The green fields of Saint-Gilles have been replaced by 19th-century urban development which, with the arrival of industries and factories, paved the streets with concrete and stones still present today.

A Christmas novelty

So, how did the Saint-Gilles Sprotje become a Christmas tradition in the UK? It seems to have been a question of good timing.

Food historian Samantha Bilton believes that Victorian Britain most probably fell in love with the novelty of eating small cabbages. This popularity led to its inclusion in roast dinners, at a time when the concept of having roasts for Christmas was gaining popularity.

Today, a surface of 3,240 football pitches is dedicated to growing Brussels sprouts in Britain – more than in Belgium. While children have often complained about their bitter taste, new research has revealed why sprouts taste better as you get older: it's genetic.

"Sulfur is responsible for the bitter sprout taste. As we age, we lose tastebuds, which can make them more palatable," said the University of Warwick's Lauren Chappell.

Sprouts are also lauded for their health benefits: they have twice as much vitamin C as the same quantity of oranges. The winter vegetable is also rich in magnesium, potassium and folic acid – all persuasive arguments to be used with sprout-averse children.

NB. Try roasting and not boiling them.