Belgium may be divided politically and linguistically, but one thing all regions and communities can agree on is the beloved national biscuit: Speculoos.

Much like beer, chocolate, waffles or fries, Speculoos is a staple of Belgium's gastronomic culture, an artisanal treat passed down through the generations, which is served with a coffee in cafés across the country. But how did this unassuming Belgian biscuit become the global 'Biscoff' phenomenon we know today?

The spiced, caramelised biscuit can be traced back to the 17th century when large quantities of spices were brought to Europe by the Dutch East India Company. The Dutch made the biscuits with wheat flour, brown sugar, butter and traditional Speculaas spices (usually cinnamon, nutmeg, cardamom, cloves and ginger).

However, the spices were much more expensive in Belgium so Belgian bakers then developed their own recipe and Speculoos was born ('loos' literally meaning without spices).

Taste of nostalgia

Although now available year-round, the biscuit has festive origins and is traditionally eaten on the feast day of Saint Nicholas, or Sinterklaas (who inspired Santa Claus), on 6 December. Children would leave their shoes out the night before and wake up to them full of biscuits and mandarins, having been visited by Sinterklaas during the night.

The biscuits are therefore typically shaped into figures of Sinterklaas (or his helper Zwarte Piet) using wooden moulds. The word 'Speculoos' supposedly derives from the Latin speculum (mirror): it is the mirror image of the wooden mould in which it has been made.

Sinterklaas in Speculoos form. Credit: Tartine et Boterham

But what once was a Belgian and Dutch speciality saved for Sinterklaas has now become a global sensation with manufacturers shipping the biscuits worldwide. Brussels biscuit maker Maison Dandoy is one of the oldest, having been in business since 1828 and now producing 100 tonnes of Speculoos every year. World-renowned Lotus Bakeries started up in 1932.

Lotus' recipe for success

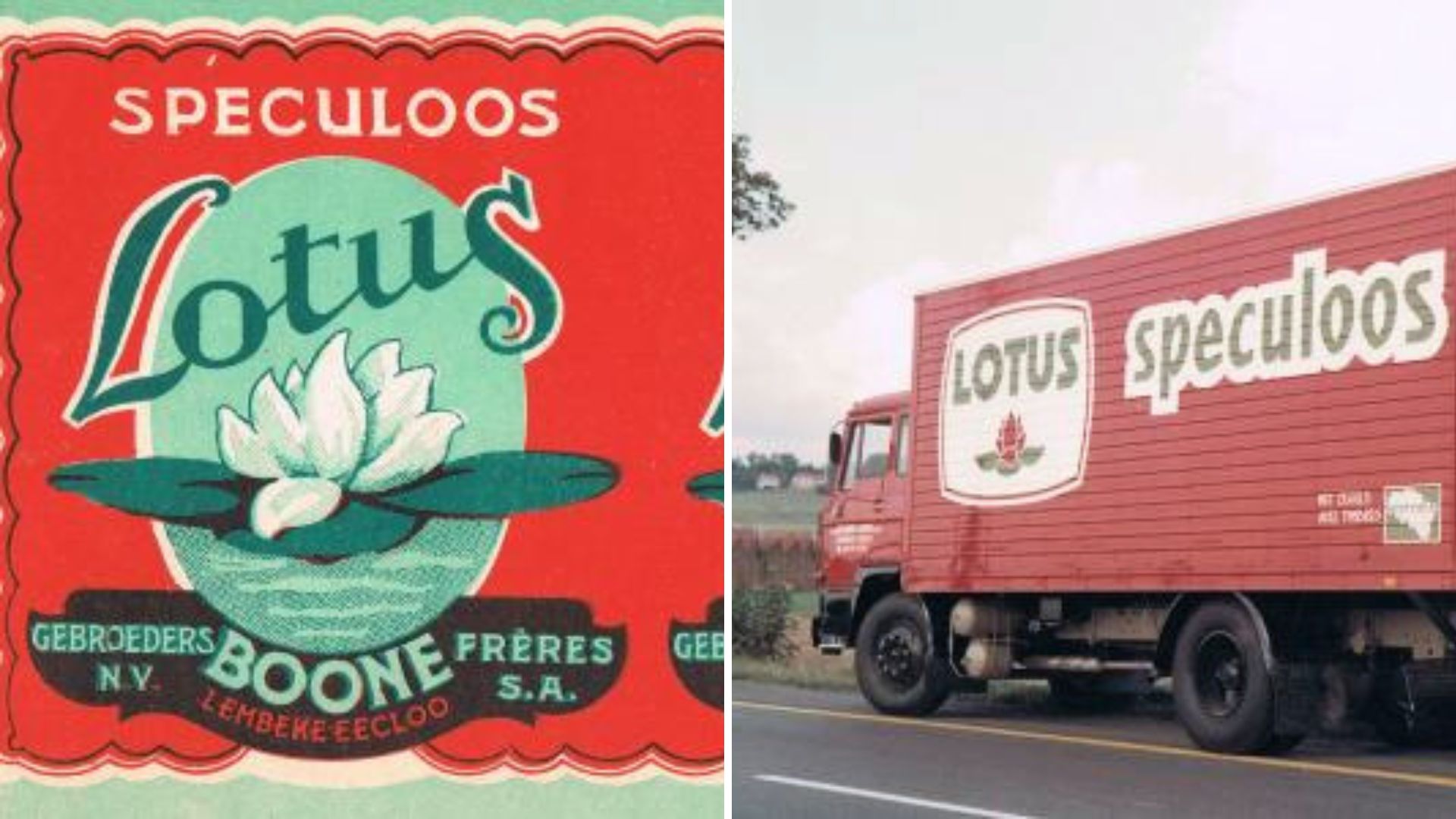

With the creation of its factory in Lembeke (East Flanders), Lotus Bakeries' founder Jan Boone Senior began manufacturing his own version of the biscuit in 1932, naming it after the symbol for purity.

Boone packaged his caramelised biscuits individually and sold them to the hospitality industry as the ideal accompaniment to coffee. The family business quickly became the nation's favourite brand of Speculoos and Boone exported them all over the world, reaching the Asian market in the 1980s and the United States via airlines in the 1990s.

440 staff are still employed in Lembeke, working around the clock to produce seven billion biscuits a year.

Credit: Lotus Bakeries

The company is going from strength to strength: in the first half of 2023, their worldwide sales rose by 20%. A new factory is scheduled to open in Thailand in 2026, according to La Libre. The share price has even multiplied by 140 in 20 years – the best performance of the entire Belgian market.

But in gaining international star status, has Lotus strayed from its humble origins?

Lotus Bakeries in Lembeke, March 2015. Credit: Belga / Jasper Jacobs

The way the cookie crumbles

The founder's grandson and current Lotus CEO Jan Boone sparked outrage in October 2020 when he announced plans to axe the Speculoos name.

In a bid to draw a wider crowd, the third-generation director wanted to replace it with the anglicised 'Biscoff' (a contraction of biscuit and coffee), regarding Speculoos too difficult for an international audience to pronounce. Until then, Biscoff was widely used but Speculoos remained on packaging in Belgium, France and the Netherlands.

But Belgians called for a Biscoff boycott and Speculoos solidarity groups were set up with the hashtag #JeSuisSpeculoos trending on social media.

Tweet translation: I will call them Speculoos 'til the day I die!

Olivier Defranne from Hainaut even created a Facebook group called 'Sauvons notre spéculoos!' (Save Our Speculoos!). "It's comparable to wanting to change the name of Montélimar nougat to an international name like 'Newga'... I'm not sure the French would like it," he told The Brussels Times. "Biscoff is utter rubbish. No one says that here."

But what makes Speculoos so important to Belgians? "It's the little St Nicholas treat – a sort of Proust Madeleine for us. Memories of shoes left by the fireplace on the evening of 5 December and filled with Speculoos, mandarins and chocolate on the morning of 6 December," Defranne reminisced. "That distinctive taste of brown sugar and cinnamon is a unique flavour that can only be found here."

'The last thing we want to do is deny our roots'

The demonised CEO nevertheless defended his reasons to De Tijd, citing brand protection and ambition: "The dream is to turn Biscoff into a global brand, one of the biggest brands in the world. If the biscuit is called Biscoff all over the world, we make that statement."

The Lotus chief also hoped the name change would avoid confusion between Belgian Speculoos and Dutch Speculaas. "The last thing we want to do is deny our roots."

Boone emphasised that Speculoos will not disappear completely: 'The Original Speculoos' can still be found on the packaging.

Many took to social media and meme-making to condemn Lotus' name change. Credit: Olivier Defranne on Facebook / michilio on Reddit

"Ridiculous!" was Defranne's response to the Lotus CEO's compromise. "We may be the land of compromise, but don't you dare touch that!"

Boone was somewhat taken aback by the social media storm. "We didn't think there would be such an emotional reaction," he told Het Laatste Nieuws. "I see it as a compliment. People really feel connected to the brand. I hope that, like us, they will become proud of the fact that a Flemish company has truly become a global brand."

The 2020 public outcry was reminiscent of when, in 2015, Colruyt Group wanted to change the name of budget beer Cara Pils. Although in this case, a petition was launched demanding the supermarket keep the name, which it did.

Lotus Biscoff in San Francisco, United States. Credit: Belga / Siska Gremmelprez

Unlike Cara Pils however, Speculoos is not technically a brand but the product itself. So it seems reasonable for Lotus to seek a rebrand when competing with other international biscuit brands to avoid Speculoos' appropriation.

"We've worked for years to protect Biscoff. Otherwise, it would be copied immediately, as far away as China," Boone told Belga News Agency.

Related News

- A Belgian history of the Brussels sprout

- Who is Sinterklaas and how do Belgians celebrate 6 December?

- Saint Nicolas arrives at Uccle school in a Porsche

But the question remains: are local products at risk from globalisation? Just a couple of months after Boone announced plans to change the name, former Brussels State Secretary for Heritage Pascal Smet recognised Speculoos as intangible cultural heritage, following requests from Maison Dandoy and non-profit Tartine et Boterham.

"Speculoos is our heritage. You don't touch that. I thank Maison Dandoy and the artisans for confidently defending the history and craftsmanship of our Speculoos," Smet stated in a press release, a clear nod to Boone.

"Now that a multinational has chosen to remove 'Speculoos' from its packaging, it is all the more important that this Brussels culinary heritage is valued and protected."