A young Jewish doctor in occupied Belgium set out with two comrades to wait for a train. It is 19 April 1943, and these men in their twenties are quietly waiting for the 20th Jewish transport from Mechelen to Auschwitz.

The Nazi-organised train is deporting 1,631 men, women and children from Belgium’s transit camp at the Kazerne Dossin to the most infamous extermination centre in occupied Poland. As the train stops at Boortmeerbeek, the three young men get up from their hiding positions and rush towards the train. Using a lantern and a red paper, they stop the train, pull out their guns and hold the train driver up at gunpoint.

One of the men manages to open the door of a wagon, allowing 17 prisoners to make their escape before the Nazi guards begin to shoot at them. Even after the hold-up, around 230 deportees escaped by jumping off the train as it went along at a slow pace, emboldened by the act of courage of the three young men. Out of these, 90 were recaptured, but 121 found freedom.

German trucks leave the Kazerne Dossin in Mechelen.

The names of these resistance fighters were Youra Livschitz, Jean Franklemon and Robert Maistriau. The trio had just organised the only known and successful attempt by the resistance to free Jews from a deportation train in Western Europe. Livschitz was eventually caught and executed in 1944 after being captured twice, including a James Bond-esque escape from the Gestapo headquarters at 347 Avenue Louise.

Maistriau, the one to open the door of the wagon, went into hiding in the Ardennes before being arrested. Franklemon was also caught, but unlike Livschitz, both survived the war.

This remarkable example of bravery was shared by the historian Dany Neudt, who together with professor Nel de Mûelenaere of the Free University Brussels (VUB), is leading a new academic chair to stimulate the scientific research on the Belgian resistance at the Dutch-speaking university of Brussels.

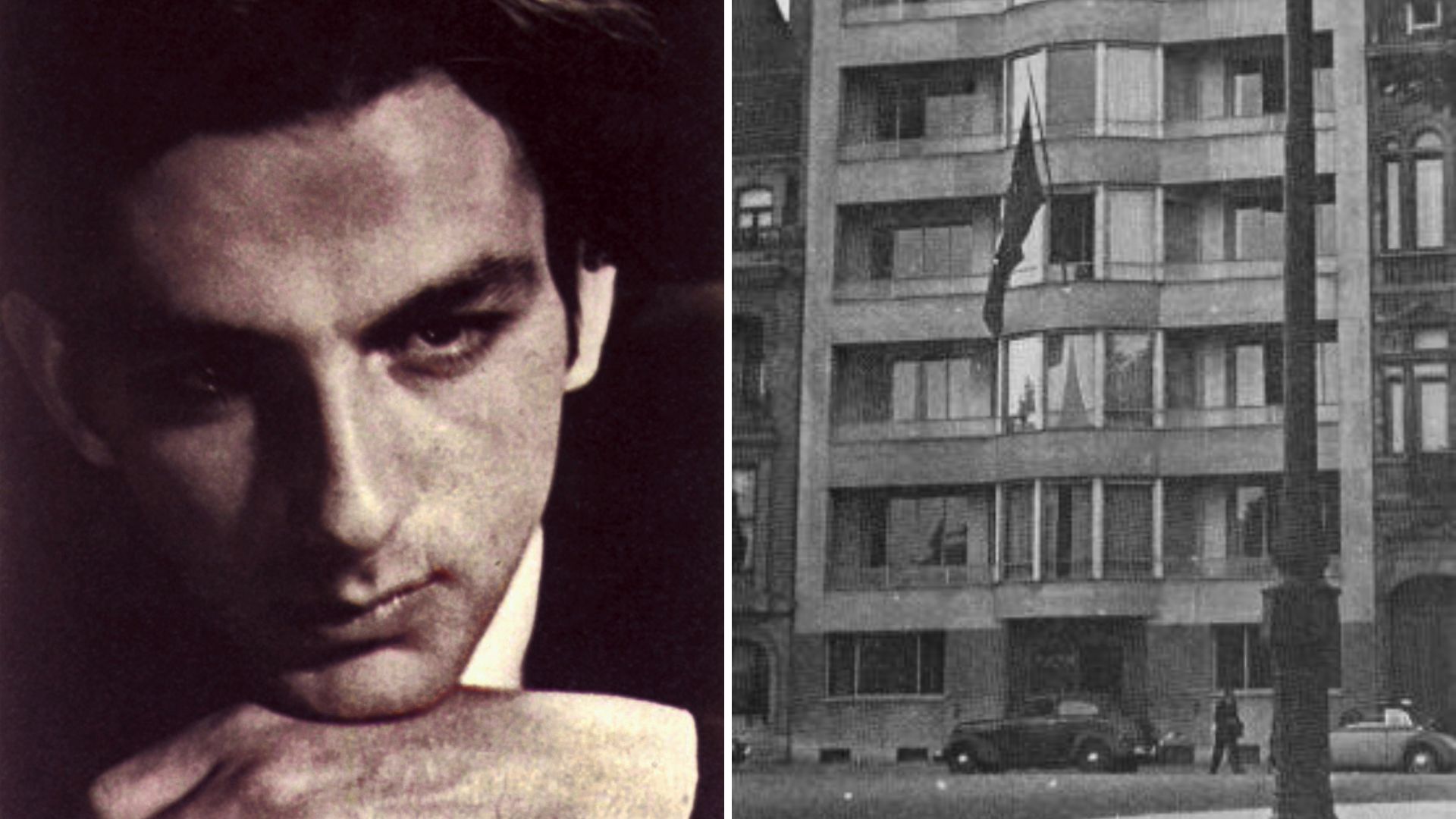

Youra Livschitz and the headquarters of the Gestapo at 437 Avenue Louise in Brussels during the war.

The aim of this new research project at VUB is to shine a new light on the history of the resistance movement in Brussels, Flanders and Wallonia.

Neudt and De Mûelenaere want to set up a "true digital resistance museum," with all new findings shared with the public through social media, podcasts and lectures. They even want the public to get involved, helping transcribe letters from executed resistance members and other archive documents – all for a digital platform that will be available to the public.

"By 2030 we want every Belgian to know at least one resistance hero," Neudt tells The Brussels Times. He is the director of the Helden van het verzet (Heroes of the Resistance) organisation, and every morning at 08:00, he posts on social media a story from the Belgian resistance.

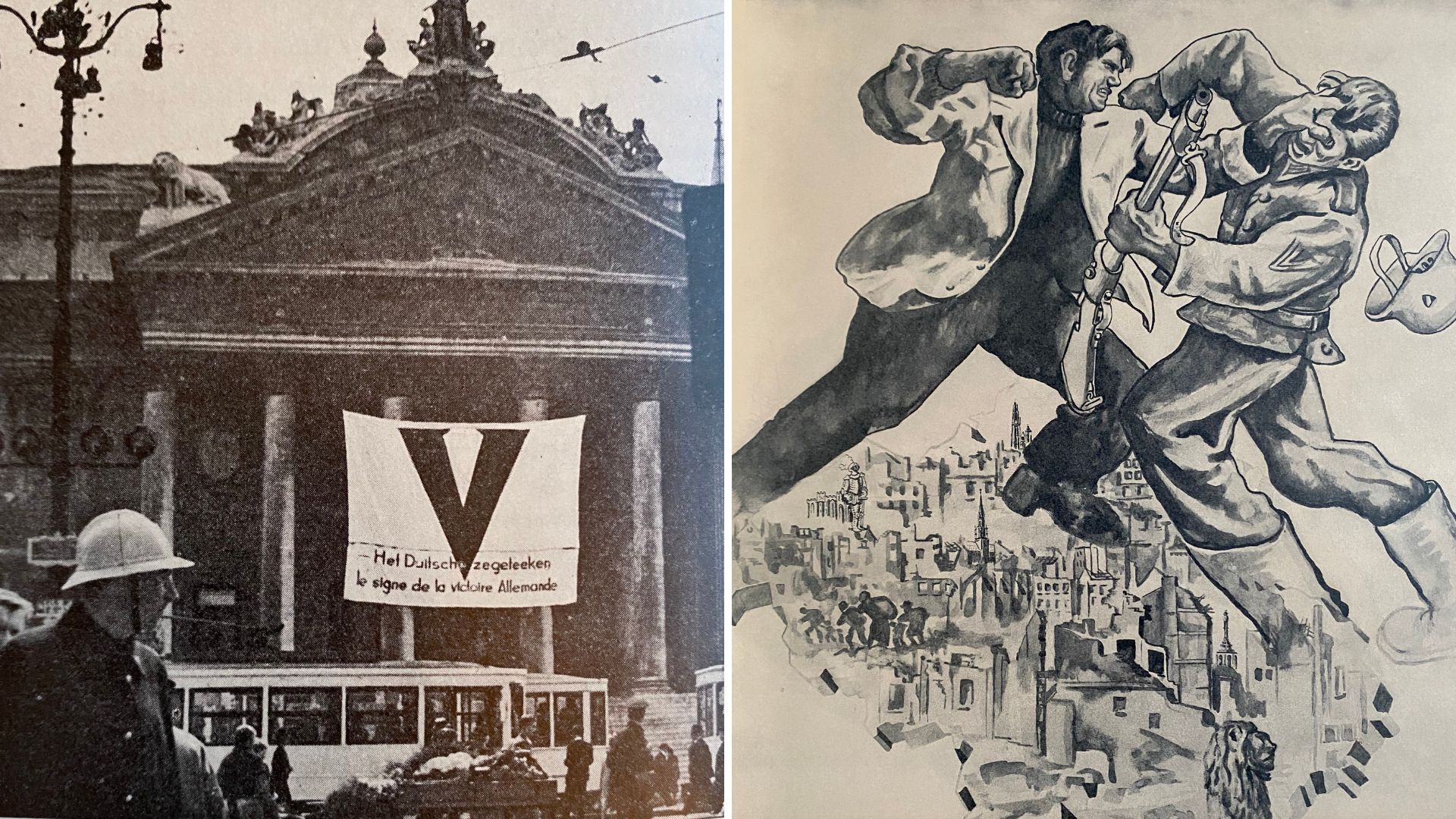

Nazi troops parade in front of the Royal Palace.

"In August 2022 I posted a mini-story with a photo of the Belgian resistance woman Suzanne Spaak, sister-in-law of the later NATO Secretary-General Paul-Henri Spaak, on X (formerly Twitter). A day later, I was surprised to find that the tweet had gone viral, even abroad," Neudt continued.

Alongside his partner Tim Van Steendam, he set up the non-profit organisation Heroes of the Resistance, self-publishing resistance novellas, and organising Resistance Cafés (in both French and Dutch) where relatives share family stories. Last May, they streamed a 48-hour reading marathon from a former concentration camp with the names of resistance members.

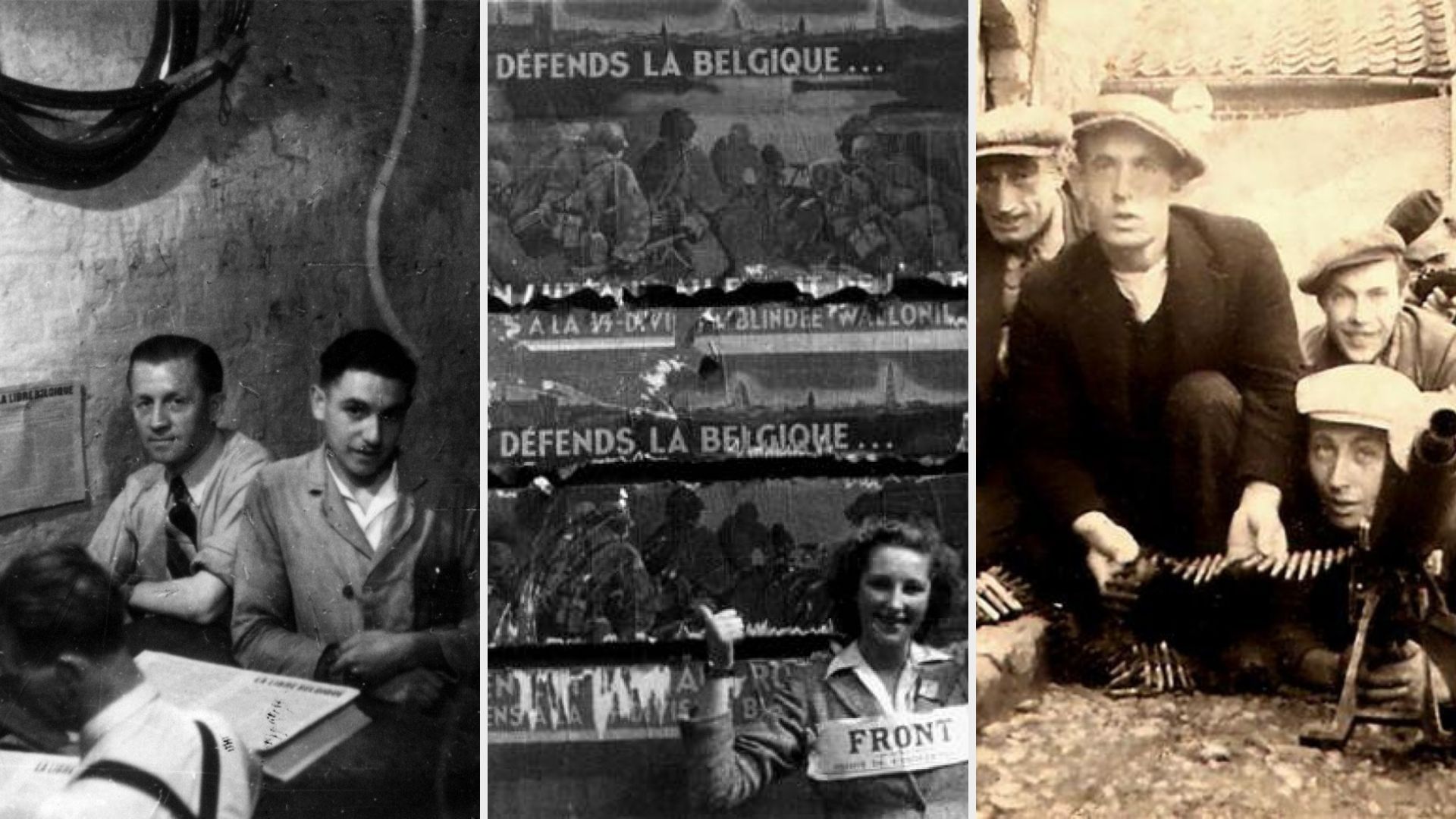

Faces of the Belgian Resistance.

As the legacies from last century’s wars begin to fade away, the aim is to preserve the memory of resistance fighters who gave their lives to defend the country from Nazi rule. Belgium was occupied from 28 May 1940 to February 1945 – and as many as 150,000 Belgians are believed to have participated in the resistance, 40,000 of which were arrested and 15,000 did not survive to tell the tale.

Why did they make that courageous choice? How did they organise in those difficult circumstances? These are the questions that VUB, Neudt and De Mûelenaere are asking themselves in the new research project – questions as relevant today as they were 100 years ago.

"Like many people, I am concerned by the increasing geopolitical tensions, the massive rise of conspiracy theories, the normalisation of the extreme right and other totalitarian ideologies," he said. "That is why, as a historian, I started to delve into the 1920s and 1930s when many citizens must have had similar feelings." He also delved into the resistance story of his grandfather, "who – like so many others – had barely spoken about it during his life."

What did the resistance do?

Like many other resistance movements, the Belgian chapter was mainly set up by the country’s middle classes after the German invasion, but the movement began to slowly pick up pace in the second year of occupation.

Germany's failure to invade Great Britain and the increased repression in Belgium (including against the country's Jewish population) all helped the movement grow. Another important moment was the end of the German-Soviet non-aggression pact, which allowed communist groups to join and grow under a unified patriotic banner, with the many clandestine resistance cells ranging ideologically from anarchist to far-right.

"The Belgian resistance was incredibly diverse: from housewives and countesses, workers and factory owners, to priests and students," said Neudt. "They also performed very diverse tasks: hiding and nourishing Jews and refugees, collecting military intelligence and delivering it to the Allies, spectacular sabotage actions, distribution of underground newspapers, and armed resistance."

The aftermath of an act of sabotage of the Belgian resistance.

The Press Association Diplomatic Correspondent reported on 21 July 1943 how the latest reports received in London revealed how the German war machine in Belgium was being damaged.

"Belgian saboteurs destroyed 35 railway engines, five trains, and 18 trucks loaded with ammunition and electric pylons, and had dynamited three lock gates and fired 233 trucks of straw. Outrages in electric power stations, mines, shipyards, industrial plants and straw and flax depots, are a daily occurrence."

The report also noted that the threat of death had little effect on members of the Belgian Resistance – forcing the Nazis to no longer announce executions, but instead sending a parcel of blood-stained clothes to Belgian families became the preferred way of announcing a regime assassination.

Many of these resistors set up networks to smuggle Allied soldiers out of occupied Belgium. One of these was Andrée De Jongh, born at 73 Avenue Émile Verhaeren in Schaerbeek in 1916 – just one year after the execution of her childhood hero Edith Cavell in the same commune during the first German occupation.

Andrée De Jongh

Like Cavell, she too was a nurse and returned to Brussels to volunteer with the Red Cross after the Nazi invasion. After setting up the Comète escape route for Allied soldiers to neutral Spain (and then to Britain), she saved thousands, accompanying 118 soldiers herself on the journey. She was eventually captured by the Germans and survived two concentration camps, dying in 2007. She was described by a British colonel as a "heroine of legend."

Nazi allies in Flanders

There is also a darker chapter in Belgium’s story in the Second World War – collaboration. As they had done during the First World War, militant Flemish nationalists (but not only) collaborated with the Germans in the hope it would achieve their goals of independence.

This legacy is still cherished by the Flemish far-right in Flanders. Just last month, a Flemish Neo-nazi group launched a crowdfund and bought the mausoleum of the known Nazi collaborator Stefan de Clerq in Pajottenland – a mythical place for Flemish nationalism.

When asking Neudt about this aspect, he explains that three persistent political myths emerged in Flanders after the war.

Firstly, the myth that the resistance mainly consisted of "semi-criminal opportunists" who only joined at the very end and especially after the war. Secondly, that the collaborators had the best interests of Flanders in mind and "naively" fell into Hitler's trap, without realising the dehumanising ideology of hate he stood for. Thirdly, that the punishment for this "error in judgement" was unjustly severe, and that the collaborators were actually the biggest victims of the war.

"For many decades these remarkable myths have been very dominant in Flanders, Neudt said. "There has been a noticeable change in recent years, mainly because scientific research has provided undeniable evidence that they are incorrect." He believes the current generation has a more rational approach to both resistance and collaboration in Flanders.

While Neudt acknowledges the rise of the far-right as a problem, he prefers to maintain an apolitical approach to studying the resistance in order to build communities and bridges.

"Today there is much more room to admit that the collaboration was wrong and appreciate the enormous courage and commitment of many resistance fighters. Our movement has the mission to promote the respectful memory of tens of thousands of forgotten resistance heroes."

This article was amended to clarify that Poland was under Nazi occupation at the time that the concentration camp was opened in Auschwitz.