Internationally, Belgium is well-known for the atrocities its then-King Leopold II and later the State committed in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) under colonial rule. Strikingly, many Belgian children are not (properly) taught about this in schools.

Between 1885 and 1908, the country now known as the DRC was under the personal rule of Leopold II who forced the native population to harvest and process rubber – a period characterised by atrocities and systematic brutality, including torture, murder, kidnapping, and the amputation of the hands of men, women, and children whose quota of rubber was not met.

In 1908, Leopold was forced to cede his colonial 'Congo Free State' to Belgium, which would administer 'the Belgian Congo' until its independence in 1960. Estimates of the number of deaths caused by Leopold's rule range up to 15 million.

When asking people who went to secondary school in Belgium what they have been taught about all this, however, the answers vary widely.

Famous photos, no explanations

"I learnt that Belgian King Leopold II had a colony in Congo, which was later taken over by the Belgian State. Not much else," Bram Verdickt (29) who went to school in Wilrijk (Antwerp) told The Brussels Times. "Some dry facts and figures, but we were never really taught what that meant for the Congolese people."

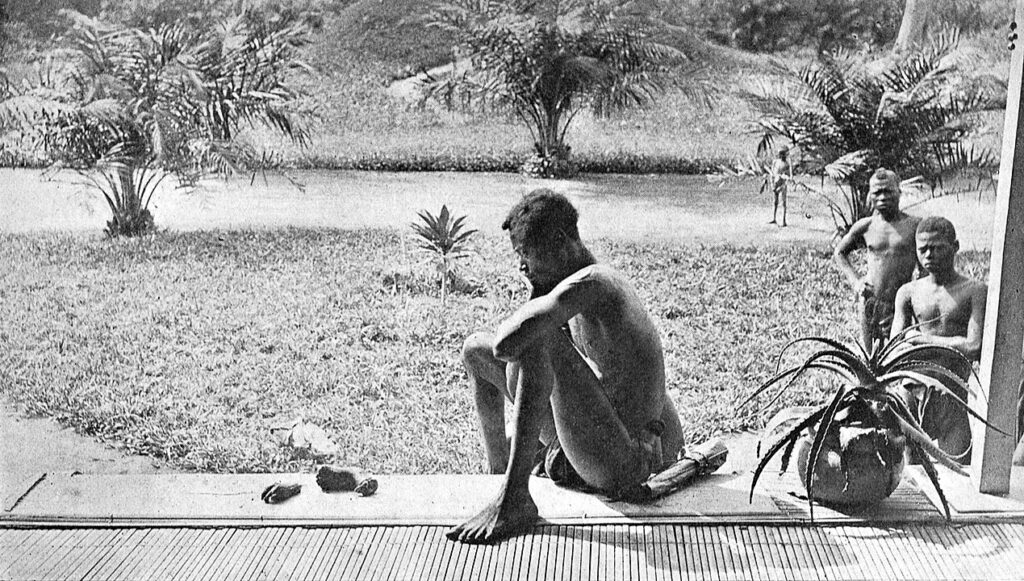

He also remembers being shown "that famous photo" of a man staring at the chopped-off hand and foot of a small child, "but only in university, years later, did I learn the story behind that image and what it symbolised."

"We only had one lesson on it, but I remember that we saw it quite in-depth," added Talia Fernandez (26), who went to school in Maasmechelen (Limburg). "Our history teacher showed some of the gruesome pictures and mainly focused on the atrocities that were committed in Congo."

However, one of Fernandez's friends, who went to the same school but was in a different class and had a different history teacher was not taught about Belgium's colony at all. "I remember asking her what she thought of the photos, but she had not even seen them."

Above-mentioned famous photo of a father staring at the hands of his 5-year-old daughter, which were severed as a punishment for having harvested too little rubber.

On the other side of the language border, the situation is similar. Laura Besong-Orok (23) went to school in Seraing (Liège) and spent about a dozen lessons in her sixth year on Leopold's private property, the role of the Belgian State, the oppression of the population, the Métis children, the assassination of the DRC's first Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, and even how this all correlates to the current violence in the country.

"We saw a few documentaries by Congolese and African filmmakers and had big class discussions about what we saw and learnt," she told The Brussels Times. "Our teacher probably had to sacrifice a few lessons on other topics to spend as much time as she did on Congo, but I am really glad that she did. My parents came here from Congo, so it is really great to get some history and context."

On the other hand, Yamil Karabulut (31), who went to secondary school in Cerfontaine (Namur), does not recall being taught anything about the subject, "apart from the fact that Leopold II was a bad man who did some bad things," he explained. "Belgium built roads and railways. That's it."

Different policies, similar issues

As with many things in Belgium, there are no countrywide rules or guidelines about how topics should be taught in school; education is organised by the country's language communities, not by the Federal Government.

In practice, this means that the Flemish Government decides the policy for Flanders and Dutch-speaking schools in Brussels, and the Francophone authorities do so for Wallonia and French-speaking schools in Brussels. This sometimes leads to different rules, different topics being taught and even different starting dates for the academic year.

One thing they have in common, however, is the lack of clear directions on how to approach the subject of Belgium's colonial history.

The removal of a statue of King Leopold II of Belgium in Gent, Tuesday 30 June 2020. Credit: Belga/James Arthur Gekiere

In Flanders, the 'minimum targets' – which define the minimum that pupils must be able to attain in their knowledge, insight, skills and attitudes before being allowed to go on the next year – are "not super detailed," Flemish Education Minister Ben Weyts' (N-VA) spokesperson Michaël Devoldere told The Brussels Times.

"These targets prescribe that students learn about colonialism and imperialism, but give confidence to the schools that they will flesh this out further," Devoldere said. "This explains why some schools pay more attention to the Belgian colony in Congo than others."

He stressed that schools simply have been given a lot of freedom in the Belgian system. "For example, the government does not prescribe how many hours should be spent on a subject such as History (or even that history should be taught as a separate subject at all), let alone that it could prescribe how many hours should be devoted to this specific aspect of history."

Making peace with the past

While the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 heightened the population's collective awareness of the atrocities committed by Belgium during the colonial period and to what extent these effects are still felt in the DRC, they have not necessarily changed how this period of history is educated in schools.

"It would be a bad thing if demonstrations determined what was taught in schools. Of course, attention must be paid to our (complete) history, but this should not happen in a political, ideological or militant context," Devoldere said.

Black Lives Matter demonstration in Brussels in June 2020. Credit: Belga/Nicolas Maeterlinck

In French-speaking education, there does seem to be the expressed will to generalise what pupils learn about the history of the colonisation of Congo in secondary schools: in 2021, Francophone Education Minister Caroline Désir announced that she will put in place a new 'common core framework.' However, this will not be implemented until 2027.

Until then, Désir intends to support teachers who already want to move forward. "If we have to wait until 2027 before anything can change in this area, that would be very long. Therefore, we want to properly equip teachers who clearly wish to get involved in teaching this part of our Belgian history, by offering resources and adapted teaching methods."

Over 60 years after the independence of the DRC, "it is time to make peace with the past," she added. "This way, we hope that all young Belgians and Congolese people will know this important part of their history better so they can better build their future."

A long way to go

As poor knowledge about Belgium's colonial past may fuel current-day racism, the country still has quite a way to go in terms of giving its history as a colonial force adequate attention.

While Belgium's current King Philippe has already taken a few big (and unexpected) steps by acknowledging what he called "colonial cruelties" and expressing his "deepest regret for the wounds of the past," the Federal Government has not issued a formal apology – as that could lead to a Congolese demand for (economic) reparations.

Amid the Black Lives Matter protests and the debate surrounding the statues of Leopold II, the Federal Parliament decided that a parliamentary commission should look into Belgium's colonial past in the Congo, Rwanda and Burundi.

Picture taken during a session of a special commission on Belgium's colonial past. Credit: Belga/Juliette Bruynseels

In that committee, MPs debated the role of the monarchy, the Church, the public authorities and the companies that benefited from the colonial regime, but also looked into questions relating to the restitution of artefacts, the visibility of the colonial past in the public arena, scientific cooperation with the three countries and the attention paid to the colonial past in education.

However, after 2.5 years of work, 300 hearings and several missions to Central Africa, the resulting 700-page report and 128 recommendations collapsed over a political disagreement at the end of 2022: the vote on the recommendations – which included that Belgium should formally apologise for its colonial past – came to a halt as liberals (Open VLD and MR) and Christian-Democrats (CD&V) left the room, refusing to participate in such a divisive discussion.

A year of standstill later, the same parties derailed the vote for a second time – preventing any vote on the text, and making it impossible for the Parliament's services to publish the report – with the committee's chair Wouter De Vriendt (Groen) saying that "minds were not ready."

Fruitless work?

However, in early February, RTBF managed to obtain the report and published it on its website, making public what the committee looked into and which recommendations it had in mind. The "colossal personal fortune" that Leopold II accumulated when ruling over the colony was considered particularly closely, as it allowed prestigious works to be carried out in Belgium, particularly in Brussels.

They also studied Belgium's treatment of the "Métis children" (who were born of an African mother and a Belgian colonial father in the colonised territories and later abducted from their mothers by the Belgian State), Belgium's role in the Hutu-Tutsi conflict and the Rwandan genocide, and the lack of research from a non-Eurocentric perspective into the colonial period in general.

For all this research work to be carried out, more funding and better access to archives is needed. Whether that funding will ever be provided remains the question; the committee's work seems fruitless as the Parliament stumbled over the question of a formal apology and the financial reparations that might result from that.

Related News

- People are 'not ready': Investigation into Belgium's colonial past at a standstill

- Belgium to pay tribute to Congolese soldiers of 1914-1918 for the first time

- Confronting Leopold’s Ghost

- It’s not just the statues, Belgium must atone for what it did in Congo

- Legacies of the colony: The lost children of Congo