October 1967. Roger Moore, six years away from playing James Bond, is in Brussels to promote The Saint TV series which made his name. He is being interviewed by the RTB public broadcaster at the wheel of Simon Templar’s Volvo P1800 coupé.

As they speed along Avenue Louise towards the Bois de la Cambre, the TV reporter is fishing for compliments about Belgium and its capital. “Vous aimez la ville?” – “It’s beautiful, beautiful, très beau.” – “Are there countries you particularly like?” – “I like quiet countries!” Moore yells over the roar of the Volvo (this is mistranslated in the subtitles as ‘I like wild countries’).

The car slips underground and his face in profile becomes a silhouette. Moore’s hesitation evaporates as fortune hands him an unlikely subject for flattery: "We don't have this in London, these nice tunnels. They're beautiful."

As the Volvo emerges from one tunnel and approaches the entrance ramp of the next, a slender, angular structure soars above its sooty neighbours, filling the windscreen to the right. This is the Louise Tower, and like the tunnels, it is almost brand new.

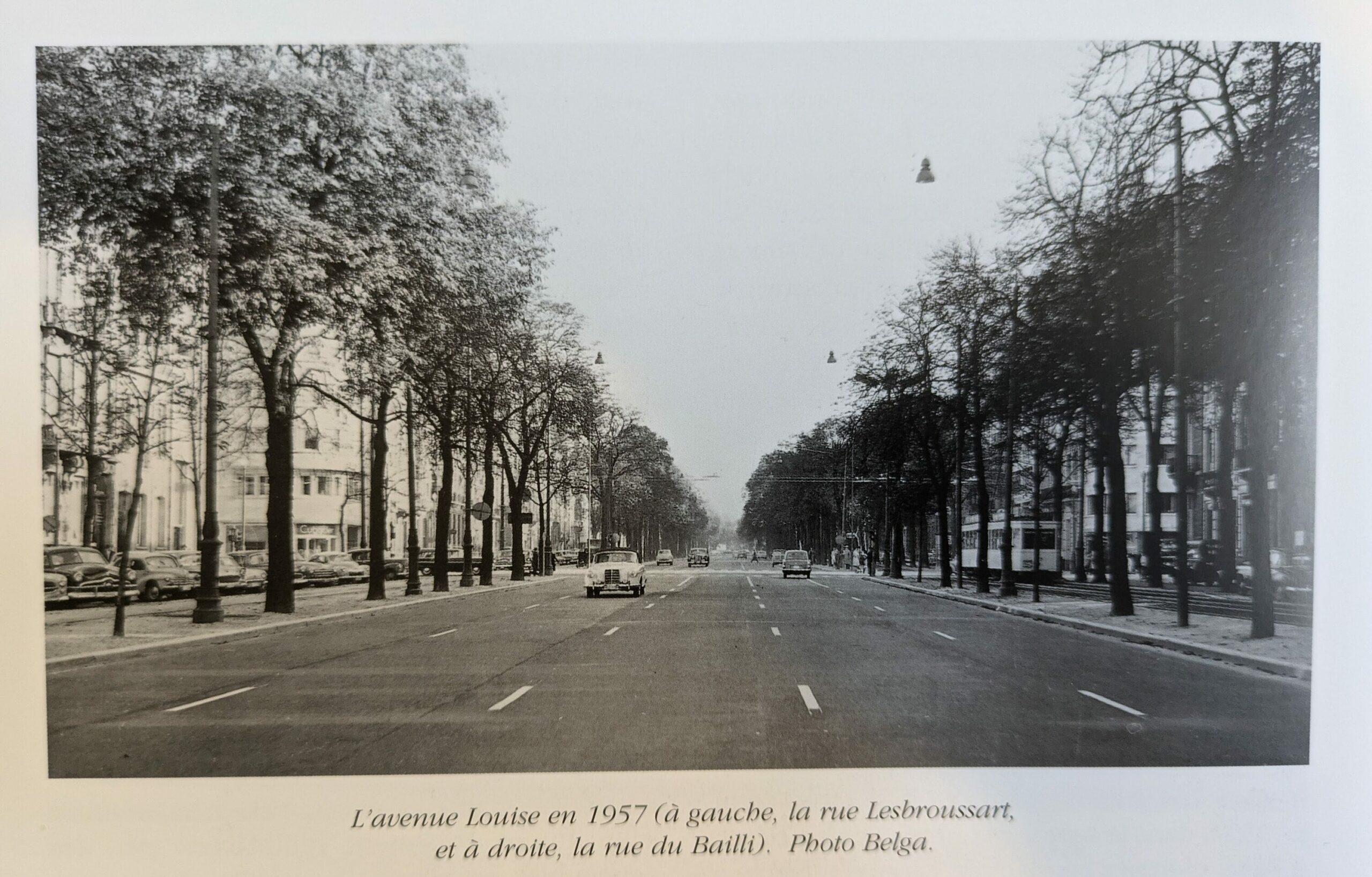

Avenue Louise before the tunnels

Thanks to “ultra-modern offices” and the century-old prestige of Avenue Louise, it aims to attract wealthy foreign corporations. Tenants already include Texaco and Union Carbide. Employees are promised “the best views in Brussels.” The expressway and tunnels will let them cruise back and forth between large suburban homes afforded by their generous pay packages or slide beneath ground in the other direction after work to catch a show in town.

Six decades on, while the surroundings appear virtually unchanged, the world has moved on. The Saint is forgotten in Belgium, and nobody cruises anywhere in Brussels anymore. The “nice tunnels”, clogged with traffic, are boring a hole in the finances of the entire region, giving them a reputation on a par with oil companies and Union Carbide.

The tower however looks as if it was built yesterday. And to a large degree, it was.

Resurrection

Stripped back to its concrete and steel skeleton in 2020, it is the latest Brussels tower to undergo a thorough renovation, due for inauguration in late November 2024.

Most recent overhauls of tall buildings in Brussels have hung the clothes of the 21st century on the discredited architecture of the postwar period, with smooth glass finishes or brighter colours. From the outside at least, the Louise Tower looks identical to the one glimpsed by Roger Moore decades ago.

The building’s owner, German real-estate group Patrizia, acquired the building in 2019. It inherited an existing partial renovation permit but decided to take the tower back to its skeleton, install state-of-the-art equipment and replace the facade in full. At the insistence of the Brussels authorities, the company had to retain the footprint and full-blooded 1960s exterior, but it made a virtue of this aesthetic constraint. “It’s our USP and popular with tenants,” says Patrizia Asset Manager Griet Heirwegh.

In the background the Louise Tower under renovation

All the tower’s steel columns are on the exterior, and seen from above, they trace out a lozenge shape, which is replicated by the concrete core of the building, containing brand-new lifts and stairs. With the load-bearing elements at the centre and periphery, space is freed up for compact but entirely open plan offices of 1,048 square metres on each of the 90-metre tower’s upper floors (including annexes there are 24 floors but no number 13, as superstition dictates).

The concentric compressed-hexagon shapes produce an interior and an exterior without right angles, a key element of the building's elegant profile which led to its protection as a landmark. The lozenge is also the logo of the building, now renamed The Louise, and is present in all signage, the same shape used by carmaker Renault (and Union Carbide).

A 60s icon for the 2020s

Number 149 Avenue Louise was built in 1963-65 to the design of André and Jean Polak, the sons of Michel Polak, creator in the 1920s of the vast Résidence Palace apartment block, one of the earliest tall buildings in the city and located in the avenue’s longtime rival for prestige, the Leopold Quarter (now more known as the EU Quarter). Their output was prodigious. After inheriting the family business in 1948, they produced factories, apartments and public buildings all over Brussels and Belgium.

The Polak brothers’ best-known structure is the Atomium, designed in collaboration with engineer André Waterkyn as the symbol and main attraction of Expo 58. Evoking an iron unit cell magnified 165 billion times, its outline was the original Polak-inspired logo, representing both itself and Brussels in the run-up to the expo and ever since. Tests in a wind tunnel had shown that aluminium, a high-tech material associated with aerospace and modernity, was the best cladding for this monument to progress and optimism.

The Louise Tower when it opened

When the original owners of The Louise bought into the Polak brand in the wake of the expo, Atomium-style aluminium was also the choice for the tower’s cladding. The architects for the latest renovation, Brussels-based A2RC, spent two years examining the Polak archives in order to understand the original project and adapt it to the present day.

The building was re-clad in aluminium, in its natural silver tone for the steel columns and black for the concrete floor plates, now insulated. The glass of the facade was replaced with modern, high-performance double-glazing in the same shade of green and remained set back 85cm from the skeleton. This was an original 1963 choice, partly to reduce the heating effect of direct sunlight and partly to obscure the view, preserving workers unused to high buildings from vertigo. Coupled with air-source heat pumps and solar panels replacing obsolete HVAC tech, these choices allowed the project to cut The Louise’s energy consumption by up to 70% from previously without changing the external appearance.

A post-pandemic building

While respecting the Polaks' aesthetic choices and updating the tech, A2RC also corrected what they call the errors of the past, mostly to do with quality of life within the complex.

The low ceiling of the lobby has gone, creating a double-height space with a half-lozenge shape gallery on the mezzanine level. A benefit of the tower’s construction means that duplex levels can be created between floors.

The pharmacy business in one of the Tower’s two annexes has been replaced with a light-filled branch of eatery Fonteyne The Kitchen, entered from the street and leading back to an additional publicly accessible space encircling a new ‘Barista’s bar’. This area with its gold tones and natural lighting is the most obvious 2020s touch in the renovation, replacing a dark and inaccessible service zone.

The new facade of the Louise Tower, May 2024

A further correction of the 1960s plan is the creation of gardens on previously inaccessible roofs. Private ones for offices next to the two annexes and a large communal space with extensive seating above the former canteen in the centre of the city block.

The philosophy of the renovation was keeping everything that worked and upgrading everything that didn’t to create what Patrizia calls a post-pandemic building. They say tenants can make net savings by leasing smaller but much more energy-efficient spaces, reflecting a world where not everyone is at their desk every day and reduced carbon footprints are key.

They can also attract and retain new generations of employees accustomed to hybrid working, thanks to brighter spaces, access to fresh air and on-site services as well as a less brutal division between the workplace and daily life in its surroundings. Heirwegh said the main attraction for Patrizia, its clients and their employees is the neighbourhood, “the mix, you have residential, plenty of restaurants and you have offices, not like a business district or the European Quarter where you only have that. And the Palace of Justice nearby for the lawyers because we have a lot of lawyers.”

CGI of the new entrance lobby inside the Louise Tower

The first tenant arrived in July: international law firm Clifford Chance, which occupies the uppermost three floors (with a fabulous view down to the law courts). The building is on track to reach 50% occupancy in November 2024, Heirwegh says, with clients drawn by the “luxury” image of Avenue Louise. In the future, that success will hinge upon Avenue Louise retaining that prestige, something it has been clinging onto for 160 years, often by its fingernails.

The creation of Avenue Louise

The origin of the busy, car-choked avenue lies a gear change or two to the northwest in the so-called Goulet, the narrowest stretch of the street closest to central Brussels. It was built in the 1840s by two entrepreneurs as part of an upscale development on a small grid of streets just outside the city at the same time the Leopold Quarter was taking shape.

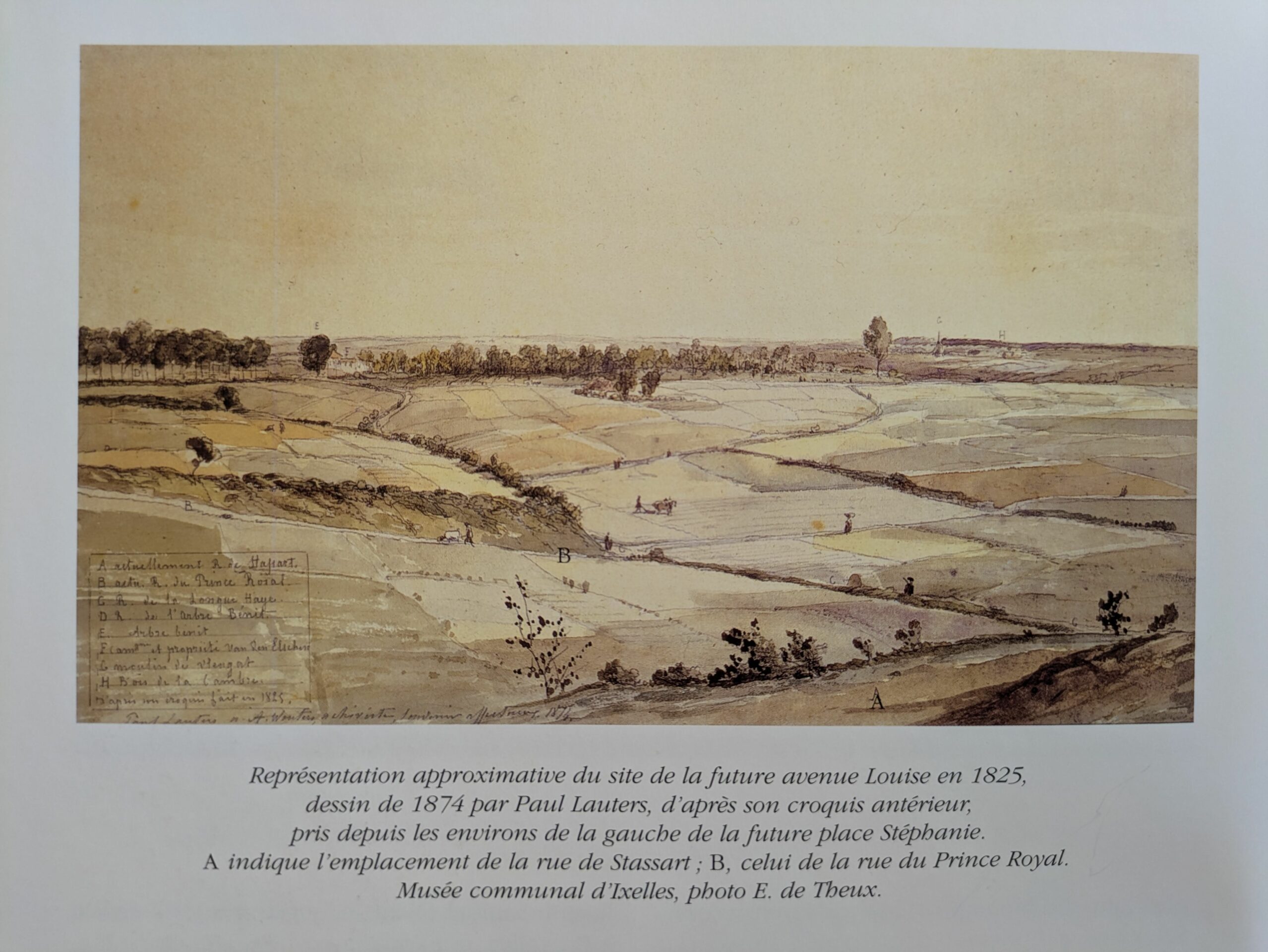

Almost immediately, plans were afoot to extend the street on a much wider scale, as far as the Bois de la Cambre, in competition with Rue de la Loi, two km to the northeast. Creating a 55-metre-wide, 2.4 km-long street across rolling countryside was beyond the means of two private citizens and the City of Brussels took over the task, annexing a wide strip of Ixelles and cutting that commune in two.

Approximate representation of the site of the future Avenue Louise in 1825, drawing from 1874 by Paul Lauters, based on his earlier sketch, taken from the area to the left of the future Place Stéphanie. A indicates the location of Rue de Stassart; B, that of Rue du Prince Royal. Ixelles Municipal Museum, Photo: E. de Theux.

Like a railway line, the new avenue required extensive expropriation of land and engineering work to create a gentle slope rising 23 metres to meet a new, landscaped version of the Bois. A ‘viaduct’ was created by filling in the 18-metre deep Tenbosch valley and, where The Louise is located now, it took six years to carve an 18-metre ‘cutting’ through high ground. The late historian (and resident) of the avenue, Xavier Duquenne spent 30 years tracking down a painting that he identified as depicting the immense excavations underway in 1862 at the future location of the Polaks’ tower.

As a road, the avenue was complete by 1869 when Belgium’s first (horse-drawn) tram route began services between the city and the Bois. As a residential neighbourhood, it took until the 1890s for the street to fill up with houses. Construction noise and brick dust were the stuff of daily life for the first generation of early adopters.

Arriving decades after the Leopold Quarter, the avenue had a very different social mix to its rival streets to the northeast which had snapped up most of Belgium’s aristocracy. But it had also learned from the urbanistic errors of the rather sepulchral stone corridors of its forerunner. From the start, the street was lined with carriageways and bridle paths lined with chestnut trees, and a 300-metre long planted flowerbed at its far end acted as a taster for the Bois de la Cambre beyond.

Avenue Louise, 1918

A red carpet

At the turn of the 20th century, these delights were enjoyed by a very wealthy selection of the population drawn from business, finance, the arts, the law, academia and those on the way up in these fields.

In 1910, there was just a sprinkling of aristocrats, such as the baroness whose house and garden sat where the entrance of The Louise is now. On each side of her were an appeal court magistrate and a member of the all-conquering Delhaize grocery family. The 149 block was bookended to the northwest by a café with an apartment above and to the southeast by the vast mansion of Nestor Catteau, a senator whose property stretched the entire depth of the block. Catteau, then calling himself Louis, had started in the 1850s with a pâtisserie by the fish market in Rue du Marché aux Poulets on the present-day location of Brucity and fought his way to eminence through restaurant ownership and domination of the Brussels catering guild.

Avenue Louise, that red carpet to the woods, was always a place that welcomed the successful regardless of background, as long as they conformed and struck the right tone. This included distinguished visitors, such as the well-groomed and beautifully-spoken Roger Moore (son of a south London policeman).

Cracks appeared in this paradise for the (comparatively) meritocratic carriage trade soon after the First World War as the housing stock began to show its age and as carriages were retired in favour of cars. Demolitions started in the 1920s, accelerating over the following decade as labour costs made large houses expensive to maintain and staff. Those who remained in the area began to stack themselves in vast luxury apartments that replaced their own houses and those of neighbours who, repelled by the increasing noise, now used the avenue as a fast access road to Brussels from their peaceful suburban villas.

Postwar reinventions

By 1945, the avenue’s prestige was at perhaps its lowest ebb. Decades of car use had devastated a roadway designed for hooves and wooden carriages and likewise, the remaining large mansions appeared to have no useful role in the street’s future. In the 149 block of Avenue Louise, Catteau’s was the first to go, replaced by the lumpen apartment block we see today, opposite Victor Horta’s Hôtel Tassel. This blighted the remaining large houses in the block, which by 1960 were used as makeshift offices while the turreted former café on the corner of Rue Defacqz was a branch of Delhaize and they would all be demolished.

When the tower, the first in Avenue Louise, was built in 1963-65 alongside the entrance ramp of the new tunnel whisking motorists below the Rue du Bailli crossroads these were statements of future intent, not intended as end points. It was expected that far more towers would follow and that through traffic would disappear into a tunnel running the entire length of the avenue. The 1969 Louiseville scheme plotted the replacement of the Goulet with an enormous ziggurat topped by two pyramids of up to 100 metres tall. A 1970 city masterplan anticipated four additional towers in the avenue proper and removed all limitations on office space at a time when this already accounted for two-thirds of the entire built volume of the street.

Of all the older buildings along it, only the two Horta mansions, the Hôtels Solvay and Max Hallet were earmarked for preservation. The 1970s oil shock, subsequent debt crises and the saturation of the office market amid competition elsewhere in Brussels (not least the avenue’s old nemesis, the Leopold Quarter) put paid to these ambitions. Just two more towers were built, amid mounting opposition from heritage groups. The two underpasses with their long approach ramps remained stubs, phase one of a scheme to properly separate fast and local traffic that never arrived, and ever since a barrier between the Ixelles neighbourhoods on each side.

Frozen streetscape

Since the 1980s, the streetscape of Avenue Louise has been largely frozen. The tunnels are worn out from traffic far heavier than they were ever designed for, and some parts have been reduced to one lane as they undergo repairs. They are ever more expensive to maintain as the Brabant countryside, eating into their ageing fabric, attempts to reclaim its territory from beneath.

Above ground, many of the avenue’s buildings, from the oldest 1860s houses to those built on the cusp of the 21st century, now benefit from protection from arbitrary demolition, reinforced by a new category of ‘legal inventory’ of heritage in force since August 2024 (yet to be seriously tested). But what are the prospects for widespread renovation in such a dismal environment?

CGI of the new Louise Tower

The owners of The Louise are betting on the quality of their development combined with the continuing prestige of the avenue. Their shiny objet d’art could play a role in rejuvenating the street, perhaps encouraging other investors to give its modernist peers a new sheen.

Late in life, as the Atomium celebrated its 50th anniversary, the surviving Polak brother Jean told an interviewer that the Atomium would always be “our best calling card, we also made the Monnaie and World Trade Centre...” in reference to their role in two of the most reviled avatars of Brusselization. Perhaps the sumptuously restored Louise Tower, or its lozenge logo, could now join the Atomium on that calling card. An improvement in its surroundings would help.

An avenue stuck in traffic

Back in the Volvo in 1967, the interviewer returns the compliment about the nice tunnels with a comment on London’s Underground, something that doesn’t yet exist in the Belgian capital. “Impossible to travel on,” grunts Moore as he powers up the ramp in front of the Hôtel Solvay. It’s the tunnels that are ‘impossible’ to use now, backed up with traffic. As are the pavements of the avenue, by the standards of the 2020s. To move between them, pedestrians must take long detours around approach ramps and high-speed stretches full of stationary cars, picking their way across patched, puddle-prone pavements past poignant fragments of tree-lined bridle paths now serving as dog conveniences.

As late as 1993, when the tower at number 149 was last renovated, then-owner insurance company Generali said the continuing prestige of the avenue depended on the tunnel being buried along its entire route. Thirty years on, whatever the solution for the tunnels may be, it is not going to be more tunnels.

Louise Tower taken from below

In October 2023, Brussels Mobility, the agency in charge of road infrastructure in the region, commissioned a study for a new masterplan to rein in the domination of cars over Avenue Louise. It promised "a pleasant and liveable commercial space: greener, safer, quieter" with fewer tunnel ramps and real cycle lanes. In other words, keeping everything that (more or less) works and upgrading everything that doesn’t.

There has been no update on the proposals since. More than two years after a permit was issued for the renovation of nearby Avenue de la Toison d’Or virtually nothing has been done and both streets remain littered with cars, parked or crawling along. Avenue Louise itself is stuck in traffic, at the back of a long wish list of projects for Brussels and the impact of the 2024 elections is still unfolding. Six decades on, the wait continues.