Once a grand vision of King Leopold II, the Koekelberg Basilica stands as both an Art Deco colossus and a polarising Brussels landmark. With its sprawling size, empty halls and a construction history spanning 65 years, this power station on a hill has hosted everything from mass to venomous snakes.

It’s one of the largest churches in the world. And, some might say, one of the ugliest. The Koekelberg Basilica sits on a hill overlooking Brussels like a massive brick power station. It dominates the view as you drive into Brussels from Ghent, a menacing symbol of Belgium’s unloved capital. Not many tourists visit the church. And it’s not the easiest place to reach. So is it even worth the effort, you might ask?

The basilica is one of Belgium’s grand follies. Like the Palace of Justice on another Brussels hill, it began its existence as one of King Leopold II’s grand architectural projects in the capital. His father, Leopold I, had already set his sights on the deserted hill to the north of Brussels, where he planned to build a royal palace on the summit. But his son, flush with the vast wealth he extracted from the Congo, had a more ambitious plan.

Leopold wanted to construct a pantheon dedicated to Great Belgians, modelled on the Panthéon in Paris where famous French figures like Voltaire, Victor Hugo and Jean Monnet are buried. The Belgian Pantheon was scheduled to be unveiled in 1905 to mark 75 years since Belgian independence. But the plan ran up against opposition.

Belgians were unenthusiastic and Leopold’s scheme was ditched before a single stone had been laid. All that now remains of his plan for a national monument are the two sweeping avenues around the Basilica named Avenue des Gloires Nationales and Avenue du Panthéon.

The ambitious Leopold didn’t give up easily. In 1902, he came up with a new plan after visiting the construction site on Montmartre in Paris where the Sacré-Coeur Basilica was being built. The builder king decided that Brussels could do something similar on Koekelberg, with a grand boulevard modelled on the Champs-Elysées linking the basilica to the city centre.

At the time, Brussels was known throughout Europe for its inventive Art Nouveau architecture. But Leopold was no fan of the progressive style invented by Victor Horta. His architectural legacy to Brussels was rooted in the past. So he summoned the Leuven architect Pierre Langerock to design a gigantic neo-gothic church with six tall spires – the tallest in the country – that would dominate the northern skyline.

Leopold was prepared to fund the project himself with his vast wealth. The elderly king turned up to lay the foundation stone in 1905 during celebrations for 75 years of Belgian independence. But nothing happened on the Koekelberg summit for several years. After Leopold died in 1909, the funds dried up. When the German army crossed into Belgium in 1914, only the foundations had been laid. The dead king’s vanity project seemed abandoned.

Interwar revival

Four months into the war, with Leuven already in ruins, Cardinal Mercier was optimistically looking forward to the end of the fighting. “As soon as peace shines on our country,” he wrote, “We will rebuild on our ruins, and we hope to put the crowning touch on this work of reconstruction by building, on the heights of the capital of free and catholic Belgium, the National Basilica.”

It took four grim years of fighting to end the conflict. Encouraged by Cardinal Mercier, King Albert relaunched the Basilica project in 1919. However, the country was struggling at the time to rebuild its destroyed cities and damaged infrastructure. It didn’t have the resources, or the skilled craftsmen, to construct Leopold’s neo-gothic church.

An architecture competition was organised. The winner was an unknown architect from Ghent called Albert Van Huffel. Up until then, he had only built a handful of private homes. Now he was put in charge of one of the largest construction projects in history.

Van Huffel came up with a plan for a massive modern church partly inspired by Byzantine buildings, crowned with two towers and a dome. He produced hundreds of detailed drawings along with a beautiful scale model of the church that won the architecture prize at the 1925 World Fair in Paris. the exhibition that would inspire the Art Deco movement that swept across Europe in the postwar years. And so, Van Huffel’s Brussels basilica – still unbuilt at the time – helped to shape European architecture between the two wars.

Many Belgians had initially criticised Van Huffel’s plan. However, the prestigious international prize shifted public opinion in favour of the design. Victor Horta also praised it, as did the Dutch modernist Hendrik Berlage, and work on the basilica took off again in 1926.

But progress on the massive project was still painfully slow and Van Huffel, who died in 1935, never saw his great work completed. The building was still unfinished in late 1935 when the first Mass was held. Work had just started on the base of the dome in 1940 when Hitler’s troops entered Belgium, bringing construction to a halt for the second time. The empty site around the unfinished Basilica was planted with vegetables to feed the local population.

The workmen were back soon after the country was liberated in September 1944. Gradually, Belgium’s endlessly unfinished church began to take shape. The nave was completed in 1951, the two towers topped with miniature domes were signed off in 1953, and the south transept was completed in 1958, around the same time as the Atomium, followed four years later by the north transept.

That left the green copper dome, which was rounded off in 1969, some 65 years after the project had begun. The country had seen four kings, two world wars, and countless government coalitions. But finally, work on the world’s largest Art Deco building was over.

By this time, Van Huffel’s monumental style had gone out of fashion. In Paris, Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano were starting work on the Pompidou Centre. In Finland, Alvar Aalto was designing clean modern church interiors. The basilica on Koekelberg summit was woefully out of step with the mood of the age.

Daunting setting

The building is intimidating to visit even before you get inside. A long, straight avenue leads from Simonis metro station through the formal Parc Elisabeth. You then cross a busy road, climb some steps, climb some more steps and arrive at the main entrance. The pillars are decorated with slender carved figures by the Belgian-Danish sculptor Harry Elstrøm illustrating the Four Evangelists. But the front entrance is closed. A notice pinned to the door sends you around to an obscure side door.

And then the interior hits you. It is unbelievably vast. It can easily hold 3,500 Catholic worshippers. But on most days, when there isn’t a Mass, it’s almost empty. I counted seven people on the day I went. It’s a rare experience to walk around such a vast empty space in a city of more than a million people, right in the heart of Europe.

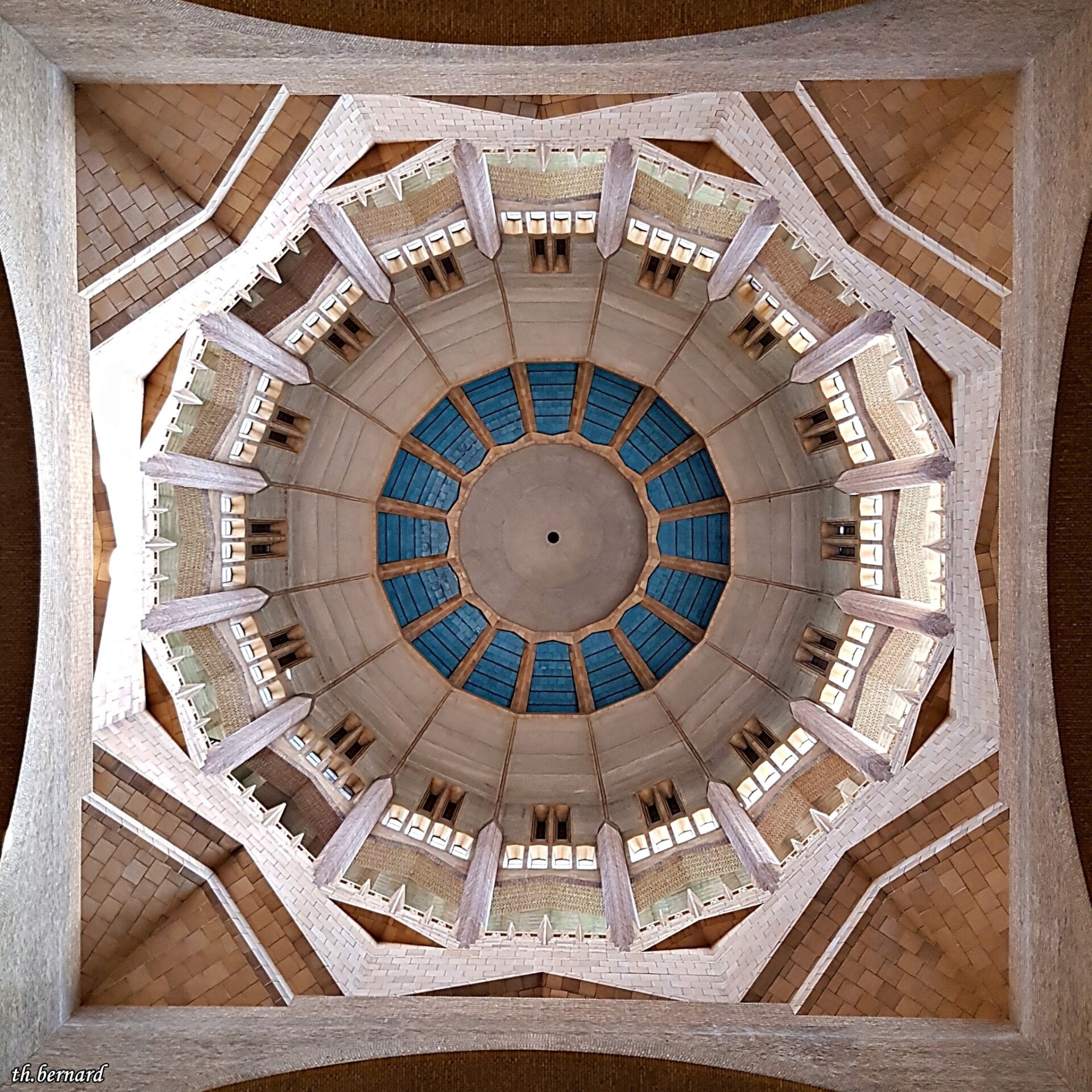

The Art Deco interior might remind you of a 1920s cinema or a Mussolini-era railway station. The frame is built of reinforced concrete, concealed behind shiny terracotta tiles and muted brown brick. There are hints of the Jazz Age style, but the overall effect is rather cold and forbidding.

Churches are normally cluttered spaces. There are paintings, statues, notices announcing pilgrimages, assorted furniture. But this basilica is almost empty, apart from the endless rows of chairs, the confessionals and a few photographs of the Pope.

Maybe this unexplored building will be rediscovered this year, as the city focuses on its exceptional Art Deco architectural heritage. And this is also the year of the Catholic Jubilee when millions of pilgrims are due to visit Rome and other Catholic churches across the world. Many Catholics will inevitably make their way to the basilica in Koekelberg.

Wandering around the building, you begin to appreciate the bold modernity of Van Huffel’s design. There are strange geometrical staircases, unusual angles, surprising views. It would make a fantastic setting for a rock concert or a dance performance.

You might think Hell will freeze over before that’s permitted by the Catholic Church. But the basilica has already been used in unexpected ways. The Koekelberg tourist office is based in one of the side chapels, while a church shop occupies the chapel next door.

Venomous guests

Some years ago, the building was the setting for an exhibition of poisonous snakes. And there was once a Dutch-language Catholic radio station called Radio Spes (Radio Hope) that broadcast from inside the basilica. Launched in 1987, it used an antenna fixed to the top of the dome until the service shut down in 2017.

The main attraction for visitors is the panoramic view from the base of the dome, 52 metres above street level. It’s reached by several hundred bare concrete steps, or by two lifts installed in 2012. One floor up, you pass the award-winning model of the church displayed in its own chapel. There’s also a small museum dedicated to the Black Sisters order, open for just two hours every Wednesday, and a museum of religious art, open on Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Sunday.

Before you head up to the roof, you can take a look at a photo exhibition that charts the agonisingly long construction history. You see King Leopold II laying the first stone, the first of 1438 piles being driven into the ground, King Albert visiting the construction site, and the religious ceremony to mark the completion in 1969.

The first-floor walkway allows you to get up close to some beautiful stained-glass windows. It’s worth pausing to look at these works designed by about 20 different artists between 1937 and 2016. The earliest windows feature angular figures that fit perfectly with the Art Deco architecture. One of the oldest windows commemorates the mothers and widows of the two world wars.

The Antwerp glass-maker Jan Huet created six gorgeous modernist windows filled with vivid faces, bright colours and religious stories. The most recent window is an abstract work created by the South Korean artist Kim En Joong.

You then follow a roped-off red carpet to reach the shiny metal lift. It makes the ascent to the rooftop an almost religious experience. You might then be slightly disappointed to emerge under the dome since the view is mainly suburban northern Brussels.

The information panels around the circumference optimistically point to distant sights such as the Hôtel de Ville on the Grand Place, the European Parliament and the Vilvoorde viaduct. You are even told that Mechelen Cathedral is visible on a clear day, although it’s hard to say whether that tiny squat structure is indeed the cathedral or a warehouse.

One thing you do notice. There are wide avenues that converge on the basilica from every direction. The message couldn’t be clearer. All roads lead to the vast Art Deco church on the Koekelberg hill.