For all the progress over the years, women still face sexual harassment on the streets of Brussels, with many avoiding certain neighbourhoods where they risk being pestered. Lauren Walker looks at why this is still an issue and asks what can be done

One evening last summer, Gitte Peeters, a 20-year-old photography student, was hanging out in a square in Brussels with her friends. It started as a fun night: they talked, listened to music and danced. But then, some men started catcalling them. After that, Peeters looked around and spotted someone filming them. And finally, a man approached her and asked, “What’s underneath your skirt?”

“It was so disgusting. It really got to me,” says Peeters, who is now an activist campaigning against casual sexual harassment. “But it was all in just one night.”

Her experience is far from unique. Sexual harassment is rife and encompasses everything from catcalling and sexual comments to unwanted touching and rape. Indeed, the broadness of the term often results in victims not being aware it has happened. A recent study of young women and girls in Brussels, Antwerp and Charleroi by children’s rights organisation Plan International, found that 91% said they had been sexually harassed in public spaces.

However, only 6% of women sexually harassed in public have ever filed a complaint with the police. “I can’t go to the police station every single time this happens to me,” Peeters says. “When I go out with a friend at night, incidents like this always happen. It’s impossible to report them every time.” Nor can women be sure they are taken seriously when they lodge a formal complaint: the only time Peeters went to the police, she was told by a female officer that it was her fault.

Normalising and victim-blaming

The inability of the police to take complaints seriously is a major barrier to women reporting harassment, says Lucas Melgaço, professor in Urban Criminology at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). “Women see the police as a male-dominated institution and not an institution made for women by women,” he says. “When you look at these numbers, it is clear that we are still a long way from having a police system where women feel represented.”

"Women see the police as a male-dominated institution." Credit: Belga

However, the police are not the only obstacles, he says, pointing out that sexual harassment often stems from structural sexism. “Generations of women have been taught to see it as a compliment, even when they are bothered by it,” Melgaço says. Shrugging off the problem and saying, ‘boys will be boys’ means many women feel pressure to accept these incidents and move on. The result is that the crimes become normalised.

This can be seen as a systemic issue. Sarah Schlitz, Belgium’s Secretary of State for Gender Equality, Equal Opportunities and Diversity says institutions that are meant to help victims of sexual harassment, including the police, are male-dominated, as are the public spaces where such crimes take place. “The public space represents a common good, shared spaces for exchange and encounters. But the harassment that women sometimes experience in the public space sends a message to women that they are not welcome there,” she says.

Making public spaces safer

Indeed, the Plan International study found that the way women interact with public spaces is influenced by their fear of being sexually harassed: it found around one in two young women feel these risks fundamentally impact their freedom of movement across the cities they live and work in.

“Some women may think they haven’t experienced sexual harassment, but then they admit they don’t walk to certain places in the evening,” says Plan International Advocacy Coordinator Catherine Péters, “If they change the way they walk, it shows that such events take away people’s freedom, and it means that the way young women think they can use public space is being affected.”

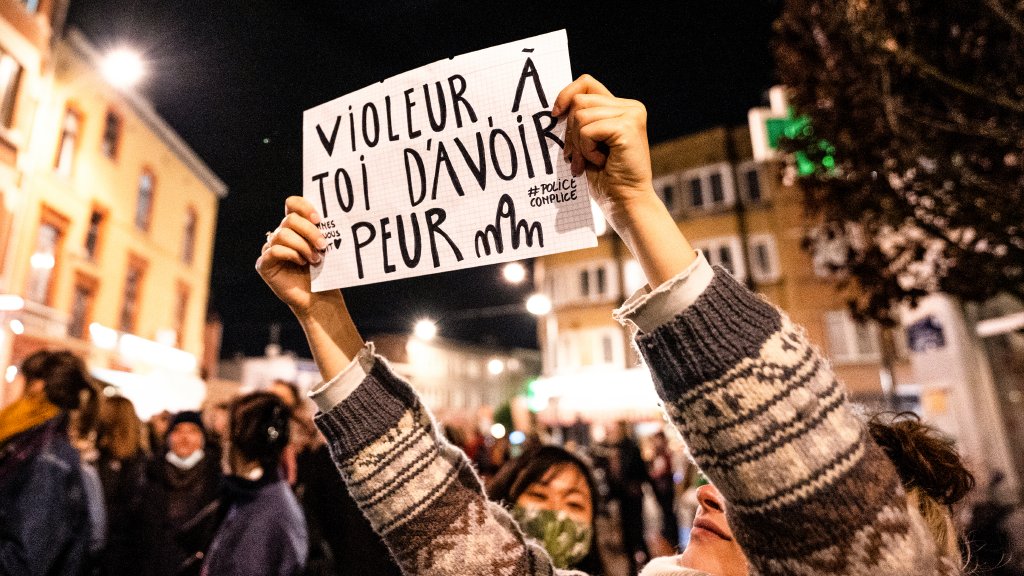

Protesters during a demonstration against sexual violence in 2021. Credit: Belga

So, how can the cycle of harassment and intimidation be broken? Plan International says youth advocacy should be part of the solution. “Young people know how they live their lives and what they experience. Everyone is becoming more aware that young people have to be included in these projects,” Péters says. “You need to have their view and to understand how they use the public spaces.”

As for tackling the root of the problem – fundamental sexism – and breaking taboos, Plan International is working with schools to help teachers educate young people. It has developed a pedagogical tool on gender as well as ‘digital training’ sessions for teachers to understand how to avoid dangerous gender stereotypes.

Improving police action

Brussels authorities accept that many women and girls have lost faith in the principle that complaints will lead to a perpetrator being reprimanded – a perception that creates a barrier to reporting, ensuring that sexual harassment does not appear on the radar.

“This is why we are working with an external partner to train police officers on the broader context of sexism, how this translates into daily life, and how officers should deal with these incidents,” says Olivier Slosse, spokesperson for the Brussels-Capital/Ixelles area. This training will teach police officers how to correctly file reports on incidents, and ensure officers treat victims seriously when they make a complaint.

Related News

- Sexual assault cases handled by Brussels authorities double in three years

- Brussels allocates €610,000 to combat nightlife sexual violence

- Belgium adopts national plan to combat gender-based violence

However, Slosse says that this is a bigger problem than just overhauling the complaint system. “The police alone cannot solve these issues, as it is a joint responsibility of society,” he says.

As for Gitte Peeters, the final straw came when she came home after one particularly bad night of being harassed multiple times. “I told my dad about it. He is an amazing, sweet man and I am sure he didn’t mean ill, but he said: ‘These things happen when you are out with the girls so late at night,’” she says. That was the moment she decided to speak out, leading awareness campaigns against sexual harassment.

Today, Peeters says that whenever she is asked how society can tackle the issue, she always starts with one basic message: improve education. “This should include telling young people that sexually harassing someone is just not the right thing to do,” she says. “Children learn from role models, including parents and teachers, about what is wrong and right. It is important that they understand from a young age that sexual harassment is not OK, why it is not OK, and what you should do when it happens.”