The Coudenberg Palace was once the grandest seat in Europe, the court of the continent’s most powerful figure. After a fire in 1731, it was flattened and covered, but its ruins can still be visited under the Place Royale.

Few of the visitors to the Royal Palace in Brussels know that for all the lavish grandiosity of the gilded staterooms, the entire structure was built on the ruins of a far more glorious palace that dominated the city’s skyline for centuries.

The residence, known as the Coudenberg Palace, was the seat of counts, dukes, regents, kings and emperors. It was the pride of Brussels until it was consumed in a blaze that, according to one account, was sparked by a lazy chef who let his jam overheat and catch fire. Coudenberg’s ruins still lurk underneath the streets, and punters can prowl through parts of the old palace, which extends into the current Place Royale and down Rue Montagne du Cour. Or, as it is known in Flemish, Coudenberg.

Coudenberg, which translates as ‘Cold Hill’, is one of the city’s many elevations, and the palace symbolised Brussels’s role as a ‘princely city’, where princes governed, noblemen schemed and artists vied to become the official court-painter. Yet, what once was one of Europe’s largest courts had humble origins as a small fortress commissioned by the Counts of Leuven and Brussels around 1100.

Back then, Brussels was a provincial market town, far from the capital city it would become. Local rulers preferred to keep the court in Leuven. But the fortress lured curious counts and dukes to Brussels, so it was no surprise the city sought to claim its place in the pecking order. When the Count of Leuven became Duke of Brabant in 1183 and Brussels received its first wall in the 13th century, the fortress slowly evolved into a proper residence.

In the 14th century, Brussels finally became a seat of power, with the ducal residence at its heart, although its initial function was still mainly defensive. That changed when it switched from a military purpose to become the principal seat of the Dukes of Brabant.

The turning point for the Coudenberg Palace came when Philip the Good (1396-1467), who already owned large swathes of the Low Countries, claimed the Duchy of Brabant after the death of his cousin Philip of St-Pol in 1430.

The so-called Burgundian Netherlands were not a unified state so the court moved around regularly, creating a healthy sense of rivalry between the key cities. Bruges claimed to be the unofficial capital of Philip’s realm, but Brussels refused to accept defeat, and launched a marketing campaign, dishing out lots of cash to revamp its surroundings.

The city bought plots of lands around the palace and initiated some major public works projects. Brussels has always been a city of builders and in 1452 they kicked off the construction of the Aula Magna, a magnificent ‘great hall’ built by master bricklayer Willem de Vogel.

All this was aimed at seducing Philip, and it worked: he agreed to stick around a bit longer. The whole process cost Brussels a pretty penny, but the Coudenberg Palace was now officially the preferred location for the court and the wider administration. Philip the Good loved bling; Brussels and its craftsmen delivered it.

Charles’s power

Dukes came and dukes went. Clever marriage strategies made the Low Countries part of the ever-growing Habsburg family, as Mary of Burgundy (1457-1482) – born at the Coudenberg Palace – wed Maximilian of Habsburg (1459-1519) in 1477.

Their grandson, Emperor Charles V (1500-1558), would become the most powerful man in Europe in the early 16th century and made his own subtle changes to the palace. He commissioned a large courtyard, expanded various wings and ordered the construction of a royal chapel which became the envy of Europe.

Royal residences were meant to dazzle foreign visitors and diplomats and Charles achieved that with swagger. The emperor would later use the palace as the dramatic backdrop for his abdication ceremony at the Aula Magna in 1555, the same hall that his great-great-grandfather Philip the Good inaugurated more than a century earlier. Brussels was now a true Princelycke Stadt, a princely city that never slept, with the Coudenberg Palace at its heart.

But more acts were to play out in the Coudenberg story. After Charles V left the scene, he was succeeded by his son Philip (1527-1598) who inherited the Habsburg Netherlands and the Spanish crowns. Unlike his father, Philip was not born and bred in the Low Countries. Locals saw him as a cold, aloof Spaniard who did not understand the Low Countries, its traditions or the various privileges dished out to the regions, cities and noblemen in the previous centuries.

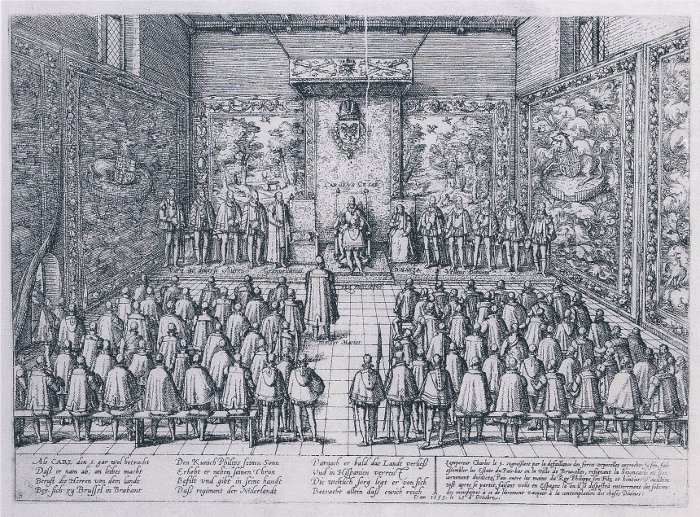

Abdication of Emperor Charles V, by France Hogenberg, 1566-1572.

Religious and political tensions were bubbling in the 1560s. Elsewhere in Europe, Protestants faced harsh persecution. On April 5, 1566, a band of 200 noblemen made their way to the palace where they were received by Margaret of Parma (1522-1586), Regent of the Habsburg Netherlands and illegitimate daughter of Charles V.

They handed over a petition which included a request to relax the stringent anti-Protestant laws and condemn the Inquisition. This event might seem inconsequential, but it was an important milestone in what would lead to a full-blown revolt against the rule of Philip II.

During the audience, one of the Regent’s advisors, Charles de Berlaymont (no, the Commission’s HQ is not named after him) mocked the band of aristocrats, calling them ‘geux’, or beggars, a description that would be used as a badge of honour by the rebels.

The subsequent uprising would cut the Habsburg Netherlands in half: the north became the Dutch Republic, while the south stayed a semi-autonomous part of the Habsburg Empire, another chain in the so-called ‘composite monarchy’.

The presentation of the petition of noblemen to Margaret of Parma, Brussels 5 April 1566, by Frans Hogenberg.

As the residence of the regent, Coudenberg remained the focal point of court life and the scene of glittering court balls and extravagant banquets. Between 1598 and 1621, under the rule of Albert and Isabella, the Habsburg Netherlands became a de jure independent state. This is seen as a golden age for Coudenberg: the joint sovereigns understood image management and used the palace to impress anyone who managed to get an audience.

Regents came and went after Albert and Isabella, all leaving small marks. Archduke Leopold Wilhelm (1614-1664) was keen on the arts and turned one of the palace’s many wings into Europe’s finest gallery, packed to the brim with Old Masters, overseen by Antwerp painter David Teniers the Younger. After Leopold Wilhelm resigned in 1656, he took much of that collection back to Vienna, which in time would form the heart of the current Kunsthistorisches Museum.

By the early 18th century, the Habsburg Netherlands had changed hands again, awarded to the Austrian branch of the Habsburg dynasty. The new regents sent by Vienna also used the Coudenberg Palace as their power base. Archduchess Maria-Elizabeth, sister of Emperor Charles VI, arrived in 1724. She would be the last ruler to live there.

Fire and burial

The Coudenberg story came to a screeching halt on February 3, 1731, when a fire erupted and spread quickly across the palace. What caused the disaster remains a mystery. Some say it started at the kitchen, while others suggest a lady-in-waiting forgot to extinguish some candles in the regent’s apartments. What is not in dispute is that efforts to douse the flames were hampered by protocol barring firemen from entering the regent’s quarters.

The fire was cataclysmic: the palace was reduced to smouldering cinders and ash in a few hours. By the next morning, all that was left were the outer walls of the royal chapel. The site would be referred to as the Cour brûlée, or burnt court, by locals. The 700-year-old Coudenberg Palace was no more.

The court carried on, however: it simply moved house to the Palace of Orange-Nassau, a stone’s throw away, where the current Palace of Charles of Lorraine is based. As for Coudenberg, it took some 40 years before the ruins were cleared and flattened, eventually becoming the Place Royale and its surroundings. Now covered with new, Neoclassical structures, the palace might never have been seen again.

But in 1980, the Brussels authorities decided to excavate the ancient cellars and open them up to the public. Today, visitors can wander through the ruins from the Place des Palais: the galleries pass under the Rue Royale and Place Royale, and exit on Rue Via Hermosa, behind the Musical Instruments Museum. If you venture down there, take a moment to imagine the court dramas that once played out in those halls.