On this day 20 years ago, Belgium became the second country in the world to legalise the rights of same-sex couples to marry.

As might be expected, the occasion will be suitably celebrated and has prompted a review of the history of the Belgian LGBTQ+ community. One dedicated archive can be found at the Suzan Daniel Funds centre in Gent, which was founded in 1996.

In Brussels, the Archives and Museums of the City have launched a call for donations of documents and items related to LGBTQ+ cultures in the region. The city's historical archives go back to the Middle Ages and now holds the official records of same-sex marriages officiated in Brussels over the past two decades.

“What enters the archives cannot be destroyed,” Chief Archivist Frédéric Boquet told The Brussels Times. “The documents belong to the city, which does not have the right to dispose of them. They will outlive us and will continue to be consulted.”

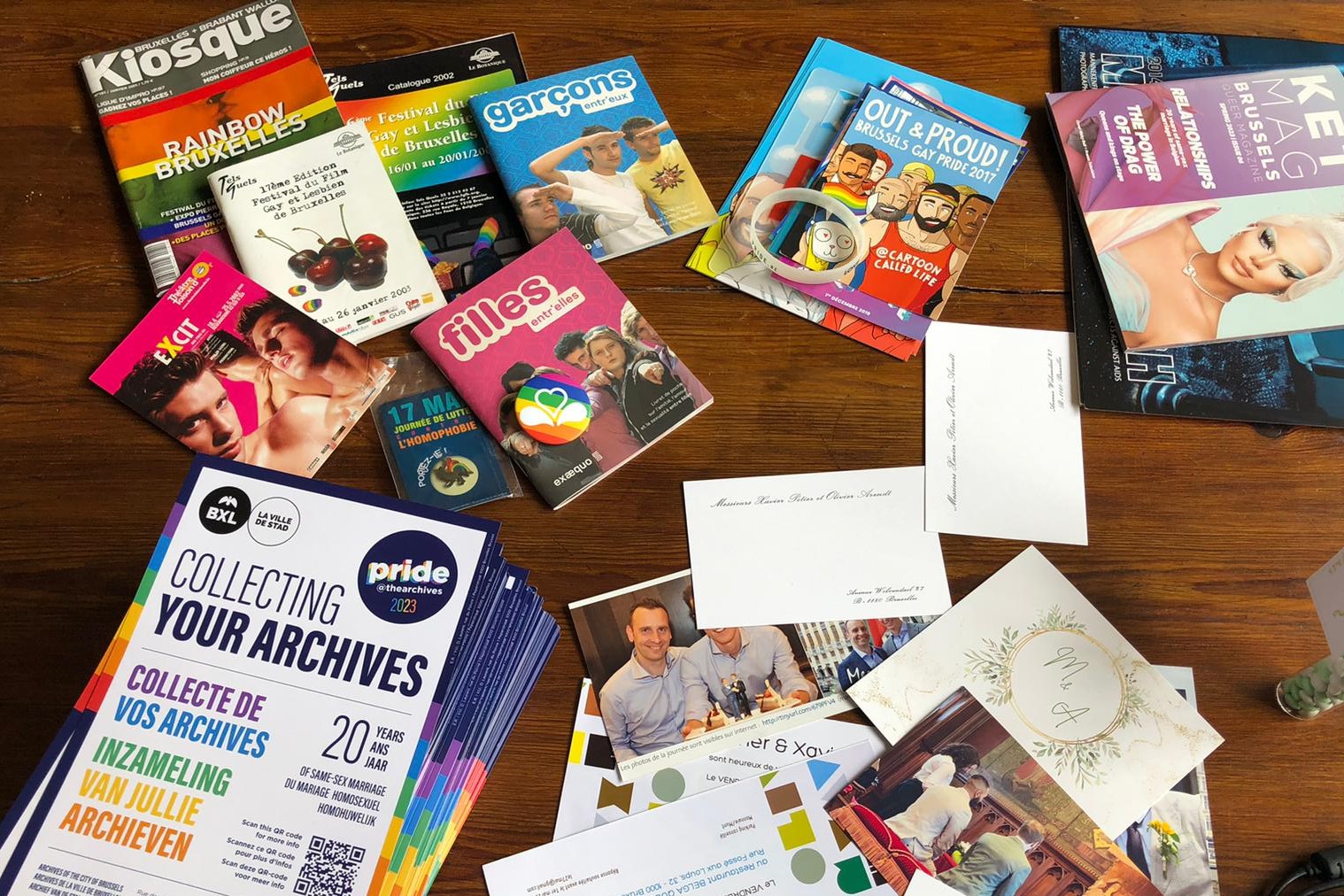

Nearly two weeks after the call was launched on 10 May, the institution received wedding invitations, photographs and wedding favours from same-sex couples, as well as calendars, information fliers and posters from LGBT events, Pride-themed bracelets and rainbow lapel pins.

Artefacts received by the City Archives in the first two weeks of the call for donations. Credit: Ioana Plesea / The Brussels Times

The call for donations is a long-term project for the Archives and will be an annual effort. Once accepted by the Archives, articles will be inventoried and made available to the public, to museums for exhibitions or to researchers (with exceptions, depending on the donor’s wishes).

Present and future interest

Artefacts such as posters, calendars and flyers will help construct a broader picture and memory of Brussels' queer history. Organisations such as Brussels Alamanack Dykes (BAD) have long been concerned with tracing queer history themselves.

The group compiles an ever-evolving map of past and present spaces of queer life in Brussels. This serves as a resource for the community, but also as a centre for documentation.

“A lot of queer history has been barred from entering official sources and publications,” notes Mia Melvær, visual artist and member of the BAD collective. But she is optimistic about the public institution’s push to include LGBTQ+ archival history and thinks that multiple kinds of queer archives should exist.

The history of LGBTQ+ communities can serve as a lesson for the present, Melvær continued: “The goal is not to have everyone memorise a lot of stories to tell around a bonfire... but it is important that we all keep in mind that we are not gradually becoming more and more progressive.”

Melvær points out that the city of Brussels used to have several lesbian bars that dated as far back as the 1930s. Today, only one exists – the Crazy Circle – which opened in 2019. The city had previously been without a bar dedicated to queer women for 16 years. The last one had closed in 2003, coincidentally, the same year when same-sex marriage was legalised.

Marion Huibrechts and Christel Verswyvelen were the first same-sex couple to get married in Belgium on 6 June 2003 in Kapellen. Credit: Belga / Peter de Voecht

“Sometimes that [idea of continuous progress] is used against us, as an argument that we should just be grateful for what we have now,” Melvær adds. The BAD members note that they appreciate 20-year anniversary of same-sex marriage, but that it should not overshadow the many battles for LGBTQ+ rights that happen today.

The challenge of including 'hidden' histories

Traces of LGBTQ+ history are not unitary. Different identities within the community had their own publications and social spaces.

Melvær noted that the gay male community tends to be overrepresented in queer historical archives, which should push archivists to give a greater voice to overlooked stories within the community.

“If you don’t take in the existing power structures, you are going to get a predictable result,” Melvær said. “If you want to find stuff from the lesbian feminist movement, you have to explicitly call for that. Even more so from the trans movement, that is more hidden and less documented.”

The Archives do not, however, have the necessary resources to extensively seek out donors and ensure that records will have representation of all parts of the community.

In 2002, around 6,000 people attended Brussels Gay Pride, as it was named at the time. Credit: Belga / Benoit Doppagne

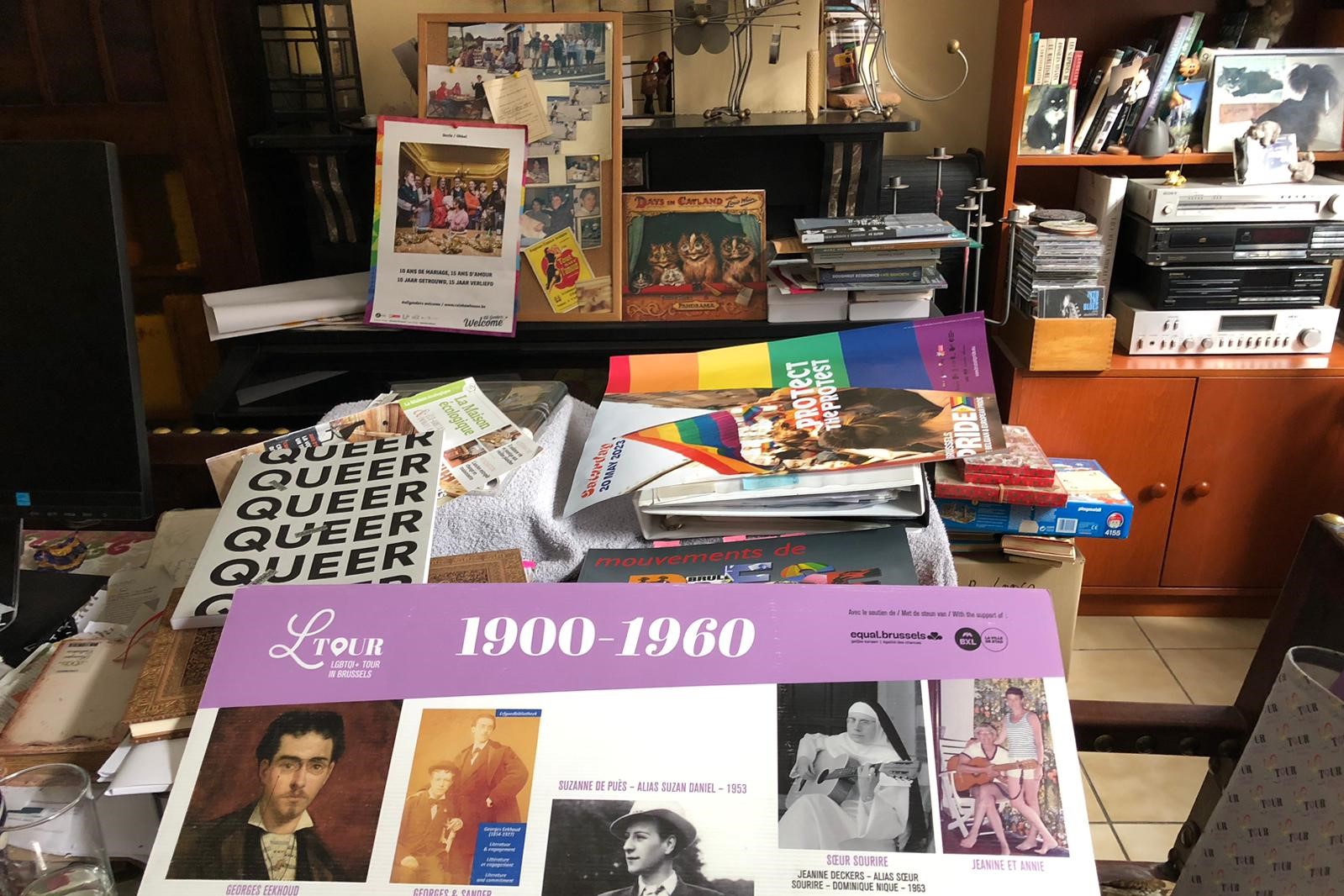

Chief Archivist Frédéric Boquet conceded that most of the recent donations have to do with male histories. But Marian Lens, a well-known Brussels lesbian activist and sociologist, holds over 40 years of queer archives in her home. Lens has contributed to archives in Amsterdam, Paris, New York, Washington, as well as more recently in Ghent.

Lens will now donate all of her 70 meters of document archives to the Brussels City Archives (linear meters are a measurement used for substantial collections).

Sprawling over three floors, shelves, boxes and photo frames, the 64-year-old has her own museum memorabilia related to lesbian, feminist and queer groups in Brussels: from magazines, t-shirts, and party invitations, to photographs of Artemys, the lesbian bookshop Lens founded in 1985 in Brussels.

At first, she was sceptical about the Archives’ initiative and unsure of how well documents would be treated. But since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, Lens was considering how to best keep her own archives.

“I wanted to make a fund, so if anything were to happen to me, they wouldn’t disappear. I wanted to protect them from my family,” Lens told the Brussels Times. “But suddenly the miracle was there: an authority that wants to keep it and wants to allocate money and people to work on it.”

“My family would just erase it and put it in a rubbish bin,” Lens adds.

Marian Lens' archives, with poster from Lens' Brussels queer history tours in the forefront. Credit: Ioana Plesea / The Brussels Times

Reclaiming the archive

Nour Outojane is a visual artist and part of His/Her/Their Stories, an initiative aiming to archive trans, intersex, non-binary and gender non-conforming communities in Belgium.

As part of the initiative, Outojane recalls looking for historical traces of these communities in various institutions: the Gent-based Suzan Daniel Funds, the RoSa feminist library, and even the City Archives. The traces that they found were sparse, however.

Instead, His/Her/Their Stories set out to archive the present, inviting people from the community to an archiving space, where they could leave traces as they wished, from recordings of conversations to photographs. Their project is not fixed on permanence but sees fleeting moments like oral stories or performances also as a way of archiving.

Related News

- Belgium launches call for projects to increase LGBTQ visibility

- 'Historic decision': 21 same-sex couples win biggest LGBTQ rights trial at ECHR

- LGBTQ community facing increased violence despite legal advances

At the moment their collective is not considering donating to the City Archives. "I am also expecting that there won't be a lot of traces of racialised queer people to go in the collections of the city," Outojane added.

The group does not want to breach the trust of the people who gave them artefacts, but they also want to represent a different kind of archiving: one that is less preoccupied with conventions but is also cautious over the ways that history and archiving have mistreated transgender communities in the past.

"Reclaiming the archiving method also means thinking about the archive differently," Outojane said. "Our practice testifies to a refusal to delegate our word as a marginalised group."