The European Union Quarter in Brussels is having an identity crisis. The European Commission says it wants to sell off many of its ageing offices near its headquarters, potentially diluting the EU-ness of the EU Quarter itself. At the same time, plans are afoot to rebuild its most emblematic and least-loved address, the Schuman roundabout, as a monument to mark “the heart of Europe”.

You could call it both less Europe and more Europe – a more symbolic Europe – in the same place.

A key sponsor of the scheme as the head of urbanism and heritage for the Brussels region, Pascal Smet, says transforming this traffic junction is one of the reasons he entered politics (he stepped down from that post in June). A theatre for protesters seeking international attention one day, the roundabout frustrates commuters and shoppers the next. The challenge of reconciling their needs with those of the politicians has been successfully resisted for decades, thanks to a fatal planning decision almost two centuries ago.

Work was due to start on the €25 million plan this summer. Motorised traffic was set to be restricted to one side of the roundabout, while a new green corridor would link it with Cinquantenaire Park, and the cluttered pavements in front of the EU’s main institutions would be rethought. The centrepiece is a ‘plenum’ – a grooved circular firepit in poured concrete. This will replace the existing worn, inaccessible space, surrounded by a low hedge making it resemble a canine convenience. But the works have not yet begun, of course.

The architects, COBE of Denmark and Brussels bureau BRUT, awarded the contract in 2017, say the design alludes to the hemicycles of the European Parliament (EU stimulus funding is paying for the scheme). It will be topped by a vast circular canopy with a dished stainless-steel base carpeted with a thatch of greenery.

“Place Schuman will be permanently accessible as a setting for democracy and knowledge sharing,” according to COBE founder Dan Stubbergaard. “It provides a place to sit, to linger, to protest, to discuss, to reflect and to discuss politics. Here, all citizens of the EU will be united under one roof.”

Under the future circular canopy

That roof will have a large, off-centre hole in it, for both aesthetic and acoustic reasons. With its curved shiny base reflecting the patterned concrete both day and night when it is lit up, renders bring to mind a mossy curtain ring.

Squaring the circle

The public inquiry into the Schuman scheme elicited many objections and little enthusiasm; of 19 recorded comments, 17 were broadly negative. Complaints included the expense, an insufficient impact assessment, and poor consultation, placing EU institutions’ desires above those of local residents. As well as the sparseness of foliage, there were concerns about traffic and accessibility between neighbourhoods.

Under the region’s scheme for multimodal specialisation, pedestrians, cyclists and drivers in reorganised streets will be assigned airline-style categories such as ‘comfort’ or ‘plus’, depending on their hierarchy in the thoroughfare in question. However, the scheme’s promoter, Bruxelles Mobilité, the regional infrastructure and mobility agency, filed a modified version of the permit in April 2023 maintaining two-way traffic on Avenue de la Joyeuse Entrée on the west side of the park. After postponing a decision for the scheme over the summer break, Brussels City announced its conditional approval on September 1."

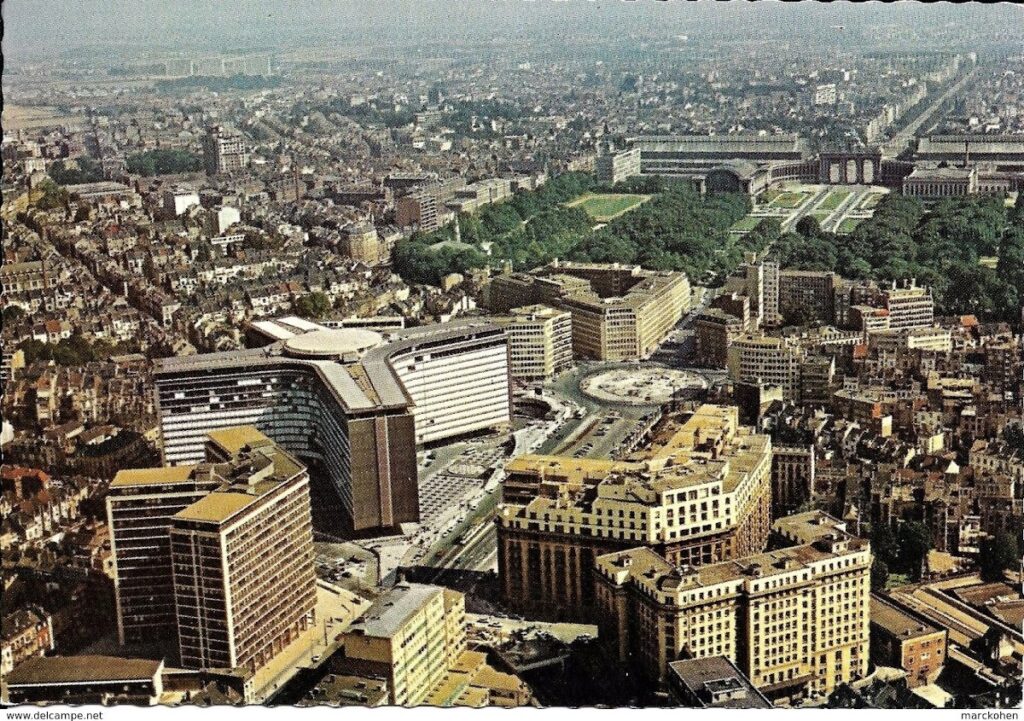

Aerial photo of the area in 1930

Urban planning is always an attempt to square the circle. But while the neighbouring commune of Etterbeek was bought off with that tweak to traffic management and extra greenery has been promised, keeping the six-metre-tall canopy is a dealbreaker for the promoter.

And it may yet break the whole deal itself. Echoing public concerns about the scale of this proposed street ornament, the Royal Commission for Monuments and Sites (CRMS in French, KCML in Dutch) issued a second unfavourable opinion on the canopy in April 2023. This panel of specialists, consulted when a project affects heritage, believes the canopy will block the historic view down Rue de la Loi towards the 1905 arcade of the Cinquantenaire.

Aerial in 1987

The promoter denies this, observing that if you stand in the right spot, the view isn’t spoiled. However, CRMS wants a thorough study into the visual impact of a 40-metre wide, turf-topped metal doughnut. While the CRMS is a consultative body without the power to block developments, its opinions carry great weight with the Conseil d’État, Belgium’s highest administrative court, which can.

Etterbeek had threatened to lodge an appeal with the court and a group of neighbourhood associations already has. An appeal over the permit for the redevelopment of another emblematic Brussels square, Place de Brouckère (for which the CRMS issued an unfavourable opinion) was upheld by the Conseil d’État in April 2022 and work on the project has been frozen ever since.

To sum up, the CRMS wants the east-west view preserved, local retailers object to dividing the quarter north-south, motorists arriving from outside the region want to access the centre rapidly, pedestrians and cyclists want to move unimpeded by motorists, bus users want direct passage across the site, the regional government wants an architectural statement and a pedestrian corridor to the park, where Etterbeek wants two-way traffic to remain.

The EU institutions paying for the work want an agreeable environment for their workers and a visible symbol of their democratic ideals, and Brussels City wants to associate the scheme with the upcoming celebrations of Belgium’s 200th anniversary in the park next door.

So how did we get here, where such a dizzying palette of stakeholders, local, regional, national, and European fight for their aspirations to be painted on such a tiny canvas? To answer that question, we need to start 1.5km away and 250 years ago on the northwest corner of the Parc de Bruxelles.

First Leopold Quarter

The EU quarter owes its origins and grid plan to the so-called Royal Quarter of the upper town, laid out around the Parc de Bruxelles from the 1770s. When Brussels spilled out beyond its historic limits 60 years later in 1837, the private developer, the Société civile pour l’agrandissement et l’embellissement de Bruxelles, took the geometry of the neoclassical park as the guideline for a new suburb emulating London’s fashionable West End and the Chaussée d’Antin in Paris. One main thoroughfare, Rue Belliard, would emerge from the central allée of the park, with the other, Rue de la Loi, running along its northern edge.

At each extremity of the new, arrow-straight Rue de la Loi however was a precipice: the descent towards the Senne River valley downtown in the west and the Maelbeek valley in the east. The street’s western end would remain a cul-de-sac and transport terminus for decades, until bowing to topography by pursuing its course downtown via the steep curve of the Rue des Colonies.

Meanwhile, 700 metres to the east, the deep and wide valley of the Maelbeek stream was trickier. Beyond it lay a slope of sandy heathland rising to the plateau of the future Cinquantenaire Park. To the north and south were the main roads to Leuven and Wavre respectively. In between the site was essentially rural, with just a few lanes snaking along the hillside for local traffic, such as woodcutters.

Second Quarter

If Rue de la Loi was to continue its trajectory eastwards to allow the quarter’s expansion, an engineering solution was needed. An early proposal was for a spectacular and ornate cast-iron viaduct over the Maelbeek on seven 50-metre arches crowned with jarring neo-gothic pinnacles. A financial crisis however prompted the now-customary Brussels compromise. Soil removed from the eastern slope to tame its gradient was used as infill to embank the Maelbeek, allowing it to be crossed by a single modest stone arch. In a phrase dear to a Brussels planning head at the time, they would dump the mountain in the valley.

Yet the prospective cost of this eastern extension remained immense, and an added complication arose: the army invoked its legal right for a vast training ground close to the capital.

Another compromise was struck. The City of Brussels would supply the site at the end of an extended Rue de la Loi (doubling as a racecourse, this would later become Cinquantenaire Park). In exchange, the city was allowed to annex the existing Leopold Quarter, its proposed new extension, and extra land to the north. The neighbouring commune of Saint-Josse-ten-Noode bitterly opposed the loss of 58 percent of its territory as part of the deal but had no means itself to fund a scheme already deemed by the government to be in the national interest.

On April 7, 1853, parliament approved the annexation, Brussels grew overnight by 194 hectares, and plans for the new quarter dating back to the mid-1840s could be made a reality. Rue de la Loi would end at the western edge of the training ground. From a circus, roundabout or rond-point a few steps short of this point, two new roads would bifurcate northeast and southeast to join the old highways to Leuven and Wavre. These are now Avenues de Cortenbergh and d’Auderghem, and the roundabout became Schuman, renamed in the mid-1960s in honour of the recently deceased founding father of the European Community.

Reconnecting history

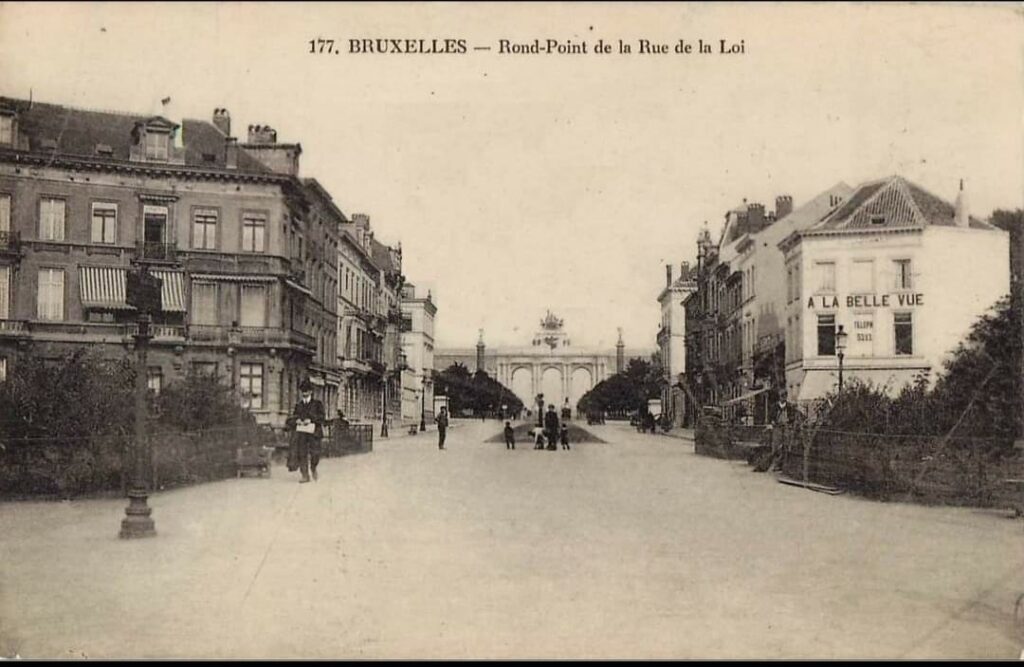

Beguiling postcards of a century ago show the circus as a place of calm and order. A peripheral Brussels neighbourhood like others, with its cafés and behatted strollers, its distinctions the half-hearted classicism of the buildings and spectacular views. Westwards, Rue de la Loi plunged down that painstakingly engineered slope and a perspective stretched as far as Rue Royale downtown.

Eastwards, the street view was closed by the Cinquantenaire Park arcade. The space was laid out by 1880 for Belgium’s 50th anniversary (after the army left for Etterbeek) and the arcade dates from the 75th celebrations in 1905. In 2030, the park is set to be the centrepiece for the 200th birthday celebrations. As part of a €155 million, seven-year plan, the tunnel emerging from the Rue de la Loi before diving again below the arcade will be covered and buildings and statues restored around the park. Brussels wants the renovation to be linked with a revamped Schuman roundabout. As the mayor said in May 2023, “It’s really about reconnecting the EU Quarter to the history of Belgium”

However, this eastern fringe of Brussels was already intimately linked to Belgian history. The park’s monuments underline this, and many have survived better than the monumental architecture that once surrounded it and led to the park from central Brussels. That includes the controversial 1921 memorial by Thomas Vincotte honouring the civilising mission of Léopold II’s Congo Free State (now targeted in the plans to decolonise the streets of Brussels). A civilising mission must of course be rooted in a civilisation, and among those who planned Brussels-over-the-Maelbeek, there was a strong urge to root the young nation as one always certain to take its place among its European peers.

The original, aristocratic-looking Quartier Léopold with its grand stone palaces was crisscrossed with streets cementing bourgeois legitimacy, namechecking Commerce, Arts, Industry, etc. Later street names placed Belgians within the canon of European civilisation. Avenue de la Renaissance runs along the park’s northern edge, and streets commemorating Leonardo and Michelangelo sit nearby, joined by Baroque masters such as Murillo and Rembrandt, and Gustaaf Wappers, whose life spanned the creation of the country.

Next to these, scientists such as Archimedes and Newton are commemorated along with a retro-fit Belgian, 16th century mathematician Simon Stevin. Around the park, streets recall tribes, many Germanic, from a misty past dear to 19th-century scholars constructing the new country’s lineage: Franks, Batavi, Nervii (after the First World War, Avenue des Germains became de l’Yser, commemorating Belgian resistance and independence). Finally, near the present-day Commission HQ, the 1st century BCE Belgic warrior Ambiorix takes his place among the historic avatars of European identity-building, Charlemagne, Clovis and Charles Martel.

Nouveau riche

This broad sweep of civilisation however failed to take root among Leopold Quarter residents. With the arrival of electricity and cars, owners abandoned their dim, draughty palaces. Initially, these became offices and embassies. Later, wholesale demolition enabled the construction of the EU’s administrative megastructures. The rich and powerful built vast new houses on the edge of the region instead and from the mid-1920s, could maintain a toehold in the city thanks to Résidence Palace, a new mountain in the valley. The arrival of this enormous complex of warm, well-lit apartments accessed by lifts, sounded the death knell in turn for the newer, eastern sector of the Quartier Léopold.

Just north of the rond-point meanwhile, a fresh injection of wealth from the Congo venture in the 1890s had helped cover the new Squares District in colourful, Art Nouveau homes. Greater national financial autonomy prompted a search for national styles in tune with the street names, providing a contrast to their monochrome neighbours in a neoclassical style imported from Italy via Paris, where previous generations of Belgian architects had trained.

A new vernacular inspired by historic Flemish architecture soon broadened as Art Nouveau harnessed Belgium’s domestic might in iron and glass production and precious woods from its colony. This culminated in the Hôtel van Eetvelde, designed in 1895 by Victor Horta for Edmond van Eetvelde, administrator of the Congo Free State. Horta had an almost unlimited budget to create a work of total art: the fashionable bow window or oriel feature was executed in metal over virtually the entire façade. Inside, guests would ascend an ornate, iron staircase spiralling up to a breathtaking stained-glass dome lantern, and some would be admitted to Van Eetvelde’s office, lined with Congolese mahogany.

Van Eetvelde was ennobled by Léopold II for extracting extraordinary wealth from the Congo colony but the fortunes of Squares District, the third Leopold Quarter, dipped with the King’s passing. Within a couple of years of van Eetvelde’s death in 1925, the house on Avenue Palmerston was sold, and his son the second Baron was taking the lift to his apartment in Résidence Palace. The ordinary bourgeoisie meanwhile tired of this area with its narrow facades after a generation. Many left for the semi-rustic domesticity promised in the magazines of the interwar period. They preferred detached homes in new suburbs with roads named after the plants in their larger gardens. Suburban flight and the impact of the Second World War, which scattered its inhabitants far and wide, soon put an end to Résidence Palace itself as a residence.

Destruction and renewal

In the 1960s, the Monastère de Berlaymont, a vast boarding school for girls, was bulldozed with its chapel, gardens, and tennis court. The name was kept by the new European Commission headquarters, which filled an entire city block. The remaining buildings here followed, along with scores of local businesses including cafés, small hotels, grocers and hairdressers. These were replaced with purpose-built offices for the national and international companies already sited in the area, an upgrade from their 19th century drawing rooms. An expanse was set aside opposite Berlaymont for the Council of the European Union, and by the 1990s two local streets, Rues Comines and Juste Lipse had disappeared under its postmodern bulk occupying another entire block.

Building the Berlaymont

The Schuman roundabout was barely changed despite the hugely increased volume of traffic. Tunnels built between the 1960s and 1980s to alleviate the choke point simply worsened the problem by promising fast car access to the city. By the 1990s, the gridlocked, exhaust-choked Rue de la Loi encased in a canyon of faceless institutional buildings was felt to be damaging to the image of Belgium and Brussels.

The Berlaymont completed, the Council building not yet there

In 1993, an agreement was signed between the state and the new Brussels-Capital Region to promote the international role of the capital, with notable regard to the EU Quarter. A new infrastructure agency was created to carry out this mission, Beliris, its name derived from an abbreviation of the word Belgium and the flower that symbolises the Brussels region (which once thrived along the brooks of what became the EU Quarter). 2023 marks the 20th anniversary of an accord to create a “space for Europe” at Schuman and move all traffic underground, financed by the state.

This was firmed up by a masterplan approved by the regional government in 2008, which proposed five possible means of removing traffic, four using diversions and one a new tunnel. The latter solution was retained when in 2011 the architect Xaveer De Geyter was awarded a tender to design the “space for Europe”. This plan included the roundabout’s pedestrianisation thanks to a new €37 million tunnel underneath connecting Avenue de Cortenbergh directly to Rue de la Loi for inbound cars. Above, a giant disc bent flat in the centre along its east-west axis would create two parliamentary-style hemicycles facing each other and preserve the historic view along Rue de la Loi – as each successive plan for the site has done, until now.

Tunnel vision

However, the scheme to bury the road was itself buried in 2014. Beliris blamed excessive architectural fees. De Geyter blamed cost: the state would have had to spend four times as much updating all the existing tunnels to modern EU norms. The state’s pledge to fund the new Schuman tunnel link had included the caveat “depending on the resources available”. This cancellation was an ominous portent for the disastrous legacy of four decades of car-first planning: tunnels.

A year later, concerns were raised over one of the youngest tunnels, the Léopold II (now Annie Cordy) and in January 2016, falling debris led to the urgent closure of one of the oldest, Stéphanie, dating from 1957. In 2019, the regional government estimated the cost of renovating the 26 existing tunnels at €523 million. Yet another new tunnel was out of the question and, as a stark headline in Le Soir put it: “The Schuman roundabout won’t be pedestrianised and won’t be the symbol of Europe.”

The curved shiny base should reflect the patterned concrete below

Thus Schuman represents a Brussels take on the ouroboros: an eternal cycle of destruction and re-creation. Will the canopy be built? Probably. Will it do irreversible damage to the historic view as the CRMS believes? Probably not.

Circular canopies are the itch the city just hasn’t been able to scratch in recent history. The 2012 canopy at Carrefour de l’Europe which blocks the view of Horta’s Central Station didn’t trouble the CRMS and doesn’t trouble the weather either when it wants to soak people. The same goes for the new disc sheltering place Rogier from everything but the elements. All art is useless, Oscar Wilde said, probably meaning Brussels canopies.

In the long term, however, canopies are cheaper to remove than tunnels are to build. Whatever the current plan’s outcome, Schuman won’t stay still for long. A glance at the aerial photo record of the area shows the average lifespan of a Schuman relook runs at around 25-30 years.

The pressure for full pedestrianisation will persist and meanwhile, battery technology and climate regulations promise a revolution in transport. New working approaches are already felt with the EU’s plans to reduce office space in the area. All seems certain to upend the place of cars in the city and the role of the roundabout. Born in the zeitgeist of the 1840s, the roundabout will shift its appearance for a new era. And for now, like the Manneken Pis, through each of its costume changes, it will endure, holding up the passers-by.