What is zwanze? Broadly defined, it is a uniquely Belgian-Brussels humour, in the form of wisecracks, cheeky banter or practical jokes.

But it is also something deeper: a sly form of resistance, a way of puncturing power with laughter. Think of it as guerrilla warfare, but with punchlines. A tender guerrilla campaign – one that wounds pride, not people, and leaves only a snigger in its wake.

During World War I, when the Germans seized every horse in the Marolles neighbourhood of Brussels, the children took matters into their own hands. They proudly marched broomsticks with cardboard horse heads, broken rocking horses and even twisted chimney pipes up to the German command post in the Palais de Justice.

The Brussels ‘ketjes’, a pet name for Brussels kids, even created their own version of the German Pickelhaube spiked helmet by piercing their cap, hood or paper hat with a carrot.

Goose-stepping like wooden marionettes, they formed a puppet parade, mimicking the German military march – before suddenly breaking into dribbling on the spot. When a baffled German officer asked what they were doing, the answer came, deadpan: “We are advancing towards Paris.”

This sort of tongue-in-cheek defiance has flourished in times of conflict. By June 1945, when the German occupation finally ended, the Marolles staged Dolphke begroufenis – Adolf Hitler’s funeral. A man with a painted moustache was hoisted onto a stretcher and carried through the streets under heavy mock escort.

An obituary and photographs recorded the farce. But it wasn’t just a parody: along the route, money was raised for survivors of Auschwitz and Birkenau. That blend of mischief and moral purpose – laughter sharpened into resistance – lies at the heart of zwanze.

A habit of mocking

Brussels humour has always carried a sharp edge, blending irreverence with resilience. Even outsiders noticed. The American Surrealist photographer Lee Miller, who visited Belgium after the war, summed it up crisply: “Deep in the atavism of the Belgians is Resistance.”

This rebellious, anarchic streak has long been part of life in the Low Countries. Throughout Belgian history, scholars and writers have noted a stubborn, often quiet resistance to generations of foreign occupation. A dogged non-conformism has flourished here for centuries, laughing in the face of power.

A fake funeral for Adolf Hitler organised in the Marolles district of Brussels

In his 19th-century research, René Fayt, honorary librarian of the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), described this subversive spirit: “From time immemorial, the Brusseleir has been known as a crosspatch. Defying the authorities, whether local or occupying, making fun of politics or the celebrities of the moment, twisting regulations, mocking others or themselves, have always been favourite pastimes of the capital's inhabitants.”

Brussels folk have a natural tendency to cherish pranks, puns and jokes in good or bad taste. The wittiest remarks often erupt at the most solemn moments – a funeral, a political speech, a royal parade – when someone will inevitably mutter a deflating one-liner in that unmistakable Brussels drawl.

These jokes, often delivered in a wry, dry tone, carry that accent our neighbours simply call “Belgian”, which is a subtle idiom, forged in a melting pot of different languages, cultures, accents and identities in our multilingual country. In other words, Belgium in miniature.

That constant awareness of living daily between languages and cultures has shaped a bizarre, even absurd mentality. Alongside realism, there is another realism: Surrealism. The boundary between sense and nonsense is porous; out of that ambiguity emerged not just jokes, but an entire aesthetic.

The swinging word

Out of this ambiguity come artistic masterpieces and expressions like “non, peut-être” – which looks French, but in Belgian-French means “yes, of course.” Or “Oui, sans doute,” which actually means no. In Brussels, a sentence may begin in an old Dutch dialect and end in French. It constantly swings from one foot to the other.

The word zwanze itself reflects this slipperiness. Middle Dutch – or ‘Diets’ – dictionaries define zwants (no standard spelling existed) as “a swinging movement, especially in dance.” But it could also mean the train of a woman’s dress.

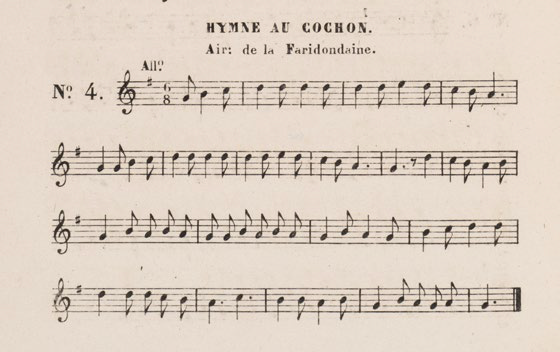

A hymn to a pig

A third meaning of ‘swans’ or ‘schwanz’ is the tail of an animal. Zwanze means swishing. It gives rise to more vulgar associations, still used in German and Dutch today – namely, a dick. A Yiddish–Dutch dictionary adds more meanings: tail, cock, a clown, a bungler. Always wagging, always shifting.

That linguistic wagging mirrors the Belgian temperament: playful, mobile, and forever teasing authority. It’s no accident that the word itself seems to grin as it’s spoken.

Parodies

Balancing between languages and identities is a hallmark of Brussels life, reflected by contemporary artists, comic strip authors, even politicians – and by the odd pirate traffic sign. One diversion sign in Brussels once replaced the Dutch word for it, Omleiding, with Arabic characters that simply read: “Good luck!”

Since the Middle Ages, humour in the Low Countries has been a form of counter step: practical jokes, hoaxes, harlequinades, carnival antics. Zwanze is like quicksilver – slippery, impossible to pin down.

Zwanzers (or zwanzeurs) enjoy teasing, with naughty, absurd, yet refined quips. The zwanzers of the 19th century were often gentlemen. Their antics were more than mischief; they were small rebellions against injustice, foreign rule, and cultural pretension, and part of the search for a Belgian identity.

Ever since Belgium declared its independence in 1830, that humour has been embraced by intellectuals, as well as the working classes.

A medal with a bum

For example, Renier Chalon, a lawyer, made waves across Europe in 1840 with the fake auction of the library of Comte de Fortsas – a library that did not exist. It was a satire of pompous, illiterate book collectors.

Lithographer and royal photographer Louis Ghémar set up a Musée Fantaisiste in a wooden shack in central Brussels (nowadays near the Place de Brouckère), filling it with 120 parodies of contemporary paintings. One of his pieces was Toile Blanche – Peinture de l’Avenir (White Canvas – Painting of the Future), a blank canvas inscribed Commande du gouvernement. A biting critique of state cultural policy, predating by 50 years the 1918 painting, White on White, by Russian avant-gardist Kazimir Malevich.

These early pranksters were, in essence, philosophers in costume. They used laughter to expose the absurdity of bureaucracy, patriotism and pretension. Their clubs – the Agathopèdes, La Société des Joyeux, Les Crocodiles – blurred the line between satire and performance art. They sang bawdy songs, issued mock manifestos and even staged their own Great Zwans Exhibitions – pre-Dada happenings long before Dada was born. The Agathopèdes even travelled to the 1851 World Exhibition in London in search of a machine à faire des canards – a “joke-making machine”.

Their philosophy was simple: laugh at everything, especially themselves. Irreverence, in their eyes, was not a flaw but a civic duty.

Zwanze links to an age-old tradition of satire. Like fairs, circuses and carnivals, it turns the world upside down, mocking the mighty and delivering a shared moment of laughter to the masses.

In 1894, Brussels zwanzers even founded their own political party, Le Diable-au-Corps, loosely translated as Devil in the Flesh. First a satirical newspaper, it later became a Bohemian café-cabaret in the city centre. And what was one of the points on their manifesto? To paint all the bare walls of Brussels. Today, that zwanze policy has been carried out in its own way: many bare walls are covered not in paint, but in iconic comic strip murals. The walls in Brussels continue to blow kisses at passers-by.

These 19th-century farces and escapades allowed artists and ordinary citizens to express their free-thinking commentary on society, politics, war and daily life. Yet there is always a note of melancholy in zwanze – a faint sigh beneath the laughter, as if to say: nothing is sacred, not even sorrow.

A puzzle of laughter

Tracing zwanze’s history is like piecing together a jigsaw. The jokes are easy to pass on, but the more intellectual, artistic side is harder to pin down. Traces survive in library archives, private collections and auction catalogues. Each discovery adds a new piece to the puzzle, making it richer and more complex.

The best definition may still come from Sander Pierron, journalist, art critic, and co-organiser of the third Great Zwanz Exhibition of 1914: La Zwanze fait penser après avoir fait rire. In other words, zwanze makes you think, after making you laugh.

It is laughter with afterthought – a chuckle that lingers. In Brussels, humour is not an escape from reality but a sly way of mastering it.