Not every resident of Brussels lives near a public park and that lack of access to green spaces is resulting in negative health outcomes for some of the city’s most vulnerable people.

Researchers from the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) spent four years mapping out the Belgian capital’s green spaces and measuring their impact on health and wellbeing. They found that while Brussels may have a high quantity of green spaces, the quality leaves much to be desired.

“We observed an inequality in terms of availability of public green spaces in Brussels,” researcher Charlotte Noël told The Brussels Times.

“If you look at the neighbourhoods towards the outskirts of the capital region, there is more green space but also a difference in terms of quality.”

Some of the reasons behind the lower quality of parks in the city centre include “a higher population density, neighbourhoods facing challenges like higher poverty and unemployment, and precarious housing conditions which tend to be in more congested areas.”

In a four-year study that is now nearing completion, Noël and other VUB researchers investigated the impact of the Brussels environment on health and wellbeing.

Available, accessible, attractive

“We learned from our research that having public green spaces nearby is perceived as having a positive impact on mental health,” Noël said. Furthermore, the availability of green spaces is associated with better personal wellbeing and lower mortality.

“From a health perspective, it's important that people use public green spaces. Therefore they should be: first, available; second, accessible; third, perceived as attractive.”

Many of Brussels’ parks fail to hit all three. Some are available and accessible, but not perceived as attractive. Sometimes they’re even deliberately avoided because they’re seen as dangerous.

“If they're not perceived as safe places where you can feel comfortable, people won't use them,” Noël pointed out.

These are parks with poor lighting, or where empty liquor bottles or even needles can be seen strewn about – indicators of drug use and binge drinking, both of which often give rise to intimidating and antisocial behaviour.

A park in the Forest neighbourhood of Brussels. Photo from Beliris.

The message such parks send, as Noël explains, is clear: “There are people that are not respectful towards their environment here. A simple empty beer bottle can create a subjective feeling of insecurity which keeps people from using public spaces, not only but especially for women.”

It can also be as simple as a bad reputation for the neighbourhood where the park is located. All of these factors contribute to a space not being utilised to its full potential and purpose.

Not such fresh air after all

Even available, accessible and attractive parks, are often not the place for a breath of fresh air. People generally assume that "in public green spaces, the air is clean and healthy to breathe. This is partly because of the trees – there's a strong association between seeing trees and breathing fresh air,” Noël said.

“It's true that there are public green spaces with no traffic, and therefore less pollution, but the other truth is that there are many other smaller green spaces that are surrounded by a lot of traffic. If there's traffic around and no barrier around the green space, then pollutants arrive from that traffic.”

In Brussels, being exposed to higher levels of ambient air pollution brings an associated risk of mortality from natural causes, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, the research indicates.

For each 5µg/m3 increment in PM2.5 concentrations, the risk of dying in Brussels increased by 17% for cardiovascular diseases and by 6% for respiratory diseases, independent of the levels of education, migrant background, and the social residential environment.

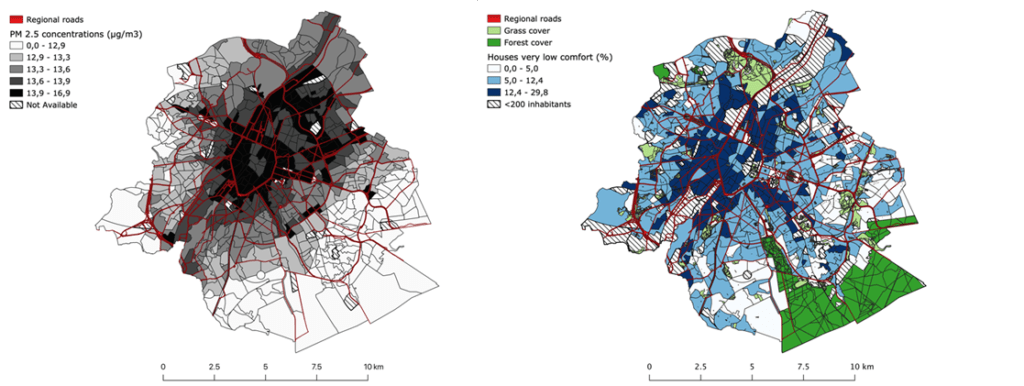

Mortality is highest in disadvantaged neighbourhoods, and researchers found that “socioeconomically deprived individuals living in Brussels are not only more exposed to harmful air pollution levels as shown in the maps below, they are also more vulnerable to its effects.”

Figure from VUB: Annual mean concentrations (µg/m3) of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) [left] and percentage of houses with very low comfort [right], per statistical sector. Sources: Air pollution data from IRCEL-CELINE, percentage of houses with very low comfort from 2001 Belgian census, and green spaces from Urbis map.

Brussels’ Minister of Mobility Elke Van den Brandt has been attempting to tackle this problem for some time now.

“Air pollution is a major issue in Brussels. If we want to convert Brussels into a healthy, liveable city, we need to address the car pressure in this city,” she said in a statement to The Brussels Times.

“We combine two approaches: a motor shift, where the most polluting cars are denied access to the city, through the low emission zone; and a modal shift, where we aim for a reduction of 25% of the current car use, through a massive investment in alternatives, and the creation of 50 low traffic neighbourhoods.”

The parks that score worst in terms of air pollution are those located in that dense centre of the city, where traffic tends to be high and housing is congested.

“Public space needs to be greened and softened. Brussels has a lot of green spaces, but they are not distributed equally over the region's territory,” Van den Brandt said. “That’s why greening and softening public space is so important.”

Some of the actions taken so far include setting a minimum of 15% greening and softening in every new project carried out on public space. In addition, more green corridors will be established, such as those recently opened in Laken, and the “Kleine Zenne Park,” a green corridor between the Ninoofsepoort and Anderlecht's Abbatoir district, which will be opened in 2023.

“We also started a vegetalisation programme to soften or green every square meter in the city that can be transformed,” Van den Brandt said. “The next big thing is a lot of small things.”

Elke Van den Brandt (left), Minister of Mobility for Brussels.

Political stakes

“During the Covid-19 pandemic, it became clear that people need public green space. More people felt the need to have public green spaces within their direct environment,” Noël said.

Some of those spaces weren’t available during the pandemic, at a time when people needed them most, due to restrictions on non-essential outings or a lack of ability to socially distance within some parks.

“The curfew also meant that some people weren't able or were less able to use public green spaces. We saw from our interviews that there were people who said they were afraid to contract the virus and therefore decided to go to the park when there were minimal people present.”

Politicians have taken a more active interest in parks, not only as a result of the pandemic but also because green spaces are increasingly seen as vital for bigger green initiatives, like reducing CO2 and convincing people to walk or bike instead of drive.

Related News

- Around 7,500 premature deaths in Belgium caused by air pollution in 2019

- 'Tough environmental reform needed' to avoid PFOS pollution scandals

- Eight new cycling projects for Brussels

Brussels is overall “a rather green region,” Noël said, with 19% of its territory consisting of public green spaces, an equivalent of 26 square metres per inhabitant.

“But of course, there are often more inhabitants than the official number,” she points out. “Brussels is a rather green region, but there's also a high population density, which makes it hard to compare internationally.”

When it comes to improving the greenness of its parks, Brussels faces a few challenges: there’s a limited surface area to work with in an old and already developed city, ownership of and responsibility for land within the region is often complicated and complex, and the financial gain that comes from creating extra green space isn’t always clear to lawmakers and stakeholders.

“The advantages of public green spaces don't translate easily into economic benefits, but of course they’re there – people feel better, happier. It has an impact on their health, work and productivity. It has an impact, but it's difficult to explain it or translate it to financial gain,” said Noël.

Regardless, the importance of available, accessible and attractive parks in Brussels remains.

“If there are future pandemics, we have to reconnect with our immediate living environment. It’s important that every person in Brussels can enjoy the health effects of public green spaces.”