Villa Empain could be the finest Art Deco house in the world, but it was not always appreciated, and almost fell into ruin.

The broad, leafy Avenue Franklin Roosevelt is one of the capital’s most handsome roads, running from Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB) to the Boitsfort Hippodrome, lined with imposing embassies and ambassadors’ residences as it flanks the Bois de la Cambre. Yet even in this splendid setting, the Villa Empain stands out for its cool, refined elegance. The broad, grey granite with gold leaf trims, measured horizontal lines and precise curves have created perhaps the world’s most exquisite example of Art Deco architecture.

Round the back, the colonnade-wrapped, azure swimming pool hints at the gilded, Gatsby-era grandeur of its conception. Inside, the astonishing atrium is decorated with five different types of marble and five different kinds of woods.

But the magnificence of the Villa Empain belies its extraordinary, troubled past, which almost saw it obliterated from the Brussels landscape. It is a tale of love, money and war, with the house at times claimed by Nazis, Soviets and – perhaps most perilously – squatters.

Let’s start this tale at the beginning, with the title. The villa takes its name from Louis Empain, the son of Belgian tycoon Baron Édouard Louis Joseph Empain and his mistress Jeanne Becker.

The father was one of Europe’s boldest entrepreneurs, with a hand in engineering, electrification, chemicals, finance, building railways, the Paris Métro, tramlines in Russia, China and the Belgian Congo, as well as founding Heliopolis, a suburb of Cairo. He founded a business empire, Groupe Empain, and an industrial dynasty that included the Banque Industrielle Belge.

Louis, his youngest son, was born in 1908 but only took the Empain name when his mother became the baron’s wife in 1921. He had little interest in the family business: after his father died, he co-ran the holding company with his older brother, Jean, but promoted measures that were considered radical and socialist at the time, like paid holidays and social insurance.

Art Deco and Bauhaus

Louis Empain’s real passion was for the arts. For his private residence in Brussels, in 1930, the-then 22-year-old hired Mexican-born, Belgian-Swiss architect Michel Polak, who also designed other iconic Brussels buildings like the Résidence Palace (1923-1926), Atlanta Hotel (1924-1928), the Électrobel headquarters (1929-1933), the Anspach department store (1927-1935) and George Eastman Dental Institute (1934-1935). The commission was for a villa that would blend the cool detailing of Art Deco with a splash of modernist Bauhaus for his plot on Avenue des Nations, later to become Avenue Franklin Roosevelt.

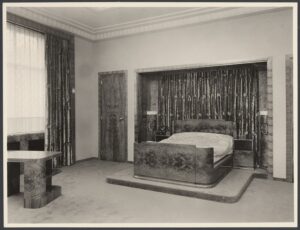

The result, completed in 1934, was a unique creation. Villa Empain has clear, functional, symmetrical lines, stripped of superfluous ornamentation. But no expense was spared on the actual materials, which included Escalette and Bois Jourdan marble inside, while the wood includes Venezuelan Manilkara, African Bubinga hardwood, gnarled walnut, grained African rosewood and oak.

The black steel gates bear a rhombi motif that recurs on the heavy front door and in the interior: on windows, skylights, balustrades, and on the marble floors. The bathrooms have intricate mosaic floors. The swimming pool, supplied with mains water, was built with a pioneering centrifugal generator that pumped the water through a filtering device and a thermostat-controlled heater. While the pool is surrounded by a wisteria-covered pergola, the garden featured a yew, two prunus, two cedars of Lebanon, and a row of fir trees along the eastern perimeter of the property.

It would have been fabulous for flamboyant parties, but Louis Empain, a sober, reclusive man, only spent a few years there. He was drawn to the wilds of Canada, spending more time on the other side of the Atlantic. After a yachting accident in July 1936, he had a mystical revelation, vowing to change his lifestyle. He sold two castles, renounced the title of baron, and donated his Villa to the Belgian state.

Empain planned to install a Royal Museum of Contemporary Decorative Arts, overseen by a Foundation carrying his name. A royal decree in April 1938 entrusted the management of the museum to poet, playwright and École de La Cambre director Herman Teirlinckx. Its president was Camille Huysmans, a socialist, former sciences and arts minister, journalist and mayor of Antwerp, who would later become prime minister.

However, the Second World War brought an abrupt end to his museum. When the Nazis invaded Belgium in 1940, the German Army requisitioned the villa in November 1943 for the Brussels Ortskommandantur - it was rumoured to have been occupied by the Gestapo, although its exact purpose remains unknown.

As for Empain, he was taken prisoner by the Nazis. Even worse, Canada mistakenly suspected him of collaborating with the Germans, and his companies in Canada were sequestrated under the Enemy Trade Regulations.

Soviets and squatters

When the war ended, Empain was unable to revive his museum. While Paul-Henri Spaak’s post-war government happily accepted the pre-war donation of the villa, it denied the existence of the Louis Empain Foundation. The government then rented the building to the USSR for their embassy in Brussels, much to the fury of the Empain family. The decision was challenged in court, but the legal dispute lasted more than a decade and Empain only recuperated the villa from the Soviets in 1963.

His Villa retrieved, Empain staged exhibitions from 1965 dedicated to kinetic and op art. He then sold it in 1973, three years before his death, to tobacco magnate Harry Tcherkezian. It was rented by the television station RTL for 20 years then abandoned, to be daubed with graffiti, vandalized and occupied by squatters.

Villa Empain might have been ruined beyond repair had it not been acquired in 2006 by Jean and Albert Boghossian, two Lebanese jewellers of Armenian origin. They wanted it as the emblematic headquarters for their philanthropic Boghossian Foundation.

By then, the dilapidated house needed total restoration, which took four years, from 2006 to 2010, during which time it was declared a heritage monument by the Brussels-Capital Region.

The restoration began with two years of site surveys and extensive research that looked at early documents, plans, images, artefacts, letters and testimonies. It drew on a 1995 report by architect Stéphane Dusquesne, who would later take charge of the file at the Brussels-Capital Region. The actual works were overseen by architect Francis Metzger, who brought in specialists with hard-to-find skills: replacing the copper roofing, restoring window frames decorated with 23.75-carat gold leaf, restoring the marble, wood, mosaics, stained glass window and wrought ironwork.

By 2011, Villa Empain was awarded the European Heritage/Europa Nostra Award, which noted “the exemplary restoration of this emblematic Art Deco monument for its quality, both in terms of the technical work carried out and the materials used.”

Today, the Boghossian Foundation in the Villa Empain is a centre for art and dialogue between the cultures, hosting exhibitions and events. That is surely what Louis Empain would have wanted.