Many medieval remnants of Brussels are in full view in the streets around the Grand Place, but the city’s origin stories have been harder to find. Until recently, that is.

Some three decades ago, an archaeological site opened under the Bourse/Beurs, which contained the tomb of the city’s first duke and remains of a 13th century monastery. Known as Bruxella 1238, it has been overhauled in parallel with the Bourse’s transformation into Belgian Beer World.

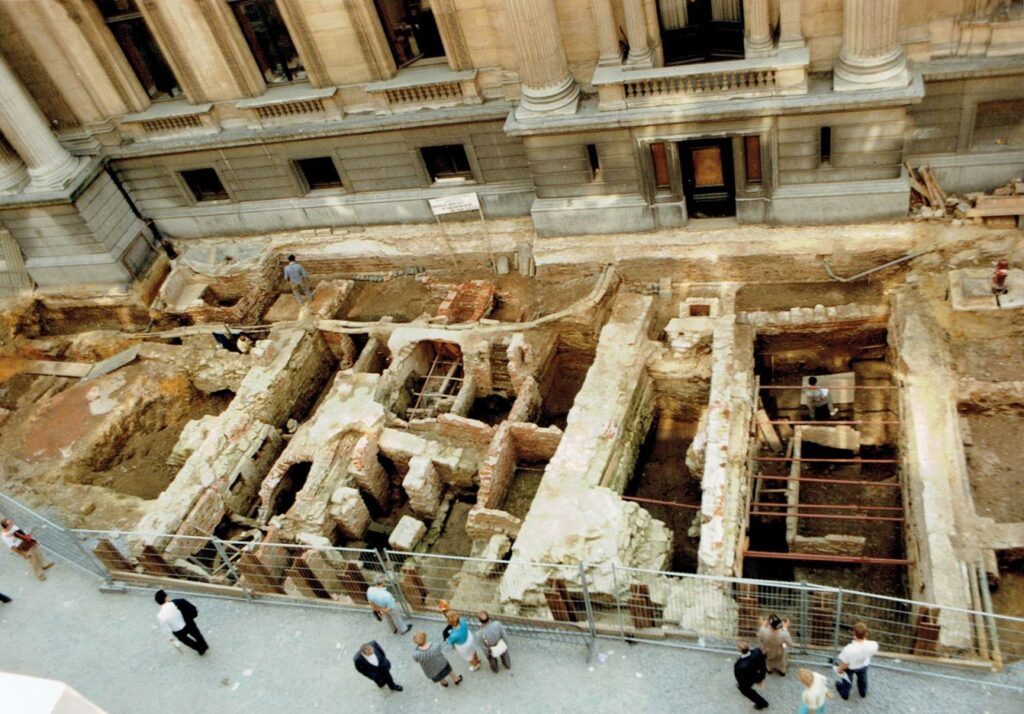

The tomb once held the mortal remains of Duke John I of Brabant and Limburg (c. 1252–1294), amidst ruins of a 1238 Franciscan monastery. First excavated in 1988, it was re-excavated and renovated in 2020-22 to showcase the history of Brussels since its founding in 979.

Bruxella 1238, initially inaugurated in 1993 as a street display, will reopen in December with a subterranean museum amidst ruins. It begins with a ground-floor introductory room inside the Bourse that relays the history from the founding of the monastery to the destruction of a 19th-century Marché au Beurre or Butter Market before the vaulting of the Senne river. Artefacts will be presented with interactive screens, while a back room will include a replica of Duke John I’s funerary monument, with the original blue stone fingers found underground.

The site retraces a millennium of Brussels’ history in new scenography and texts, burial grounds and artefacts like skeletons, ceramics, metal objects and masonry. Meanwhile, the street adjacent to the Bourse, the Rue de la Bourse, now has four giant oculi and a majestic, crown-like exit from the underground museum. They replace the previous public display in the street which had a glass roof and footbridges over the partial ruins of a church choir.

Monastery to money market

What is on display? Bruxella 1238 includes recent findings that show the site has been occupied since the mid-10th century and many people were buried there between the 13th and 18th centuries.

“We are fortunate to have an almost continuous stratigraphy between the 10th and the 21st centuries,” says Marie Vanhuysse, archaeologist for the Société Royale d'Archéologie de Bruxelles (Royal Society of Archaeology of Brussels), which led the excavation. “It considerably enriches our knowledge of the first centuries of the city.”

The inlaid floor decorations

The original monastery, occupied by Franciscan mendicant monks in 1238, had a cloister, refectory, dormitory, library, cellar, sacristy and public cemetery. It went through turbulent times during Europe’s religious wars and the bombardment of Brussels by the troops of Louis XIV in 1695 but remained until the religious order was expelled by the French in 1796.

The site was demolished and then occupied by the Butter Market from 1800 to 1867, which was then knocked down to build the Bourse, inaugurated in 1873. After more than a century as a money market, the building lost its purpose in 1996 when the stock market went electronic, omitting the need for physical traders, later becoming part of Euronext. The Brussels City took over the building in 2012, eventually restoring it and making it the home of Belgian Beer World.

Meanwhile, excavations carried out in 1988 on Rue de la Bourse by the Société Royale d'Archéologie de Bruxelles had revealed the remains of the Franciscan monastery, including a section of the cloister and some tombs, not least that of Duke John.

Excavations in 1988

The tomb was in the choir of the old church but no bones were found inside. “The duke's bones may have been taken to another location at this time,” Vanhuysse says. In the 17th century, a funerary monument was built on the duke's grave, while stones from the walls of the vault were reused as pillars to support the new monument.

Excavation techniques have evolved since 1988. “Today, it is possible to make carbon-14 dating from a small piece of coal in the mortar of masonry or to fully register an archaeological site using a 3D scanner,” Vanhuysse says. Moreover, collaboration with anthropologists and zoo archaeologists from the Royal Institute of Natural Sciences, who studied human and animal bone remains, provided new insights into life in Brussels in the medieval and modern periods.

Jan Primus to Gambrinus

The city was not a commercial, industrial or religious centre at the time, but a manufacturing hub where high-end luxury goods of tapestry, gold and silver were made. “A political conflict brought John’s mother to Brussels and he was the first duke of Brabant to consider Brussels as his main residence,” says site historian Roel Jacobs. “So, it means that this place is a testimony of the beginning of the political history of Brussels.”

Duke John’s status earned him comparisons with Gambrinus, the mythical king of beer, who he personified as a bon vivant overseeing the beer-producing Duchy of Brabant. Legend has it that John thanked his soldiers with a beer feast after his victory at the Battle of Worrigen near Cologne and addressed them atop a beer barrel – an image immortalised in a giant, golden sculpture of Gambrinus inside Belgian Beer World. Gambrinus is even credited with creating famous Brussels beers like faro and Lambic.

So, was Duke John really like Gambrinus? “No, of course not,” Jacobs says. “With Beer World, we have the two Johns in the same building. But they are completely different.”

Indeed, the duke, known in Dutch as Jan Primus, is thought to have drunk wine, like the rest of the nobility - and John’s tomb contained cups and jugs in Langerwehe stoneware, which were used as alternatives to wine glasses in the 14th century. “But if your name is Jan Primus and the name of the legendary figure is Gambrinus, and you are someone very important, it is tempting to make a connection between the two,” Jacobs laughs. “It's too beautiful not to be true.”