Animals that dwell in the woods and pastures around cities, from deer and rabbits to owls and frogs, have spent aeons trying to adapt as encroaching humans slowly squeeze them out of their natural habitat. But Brussels is trying to change this through a variety of schemes aimed at restoring the environment.

One of them is helping red squirrels commute across their arboreal neighbourhoods thanks to ropes strategically placed there by their former human antagonists.

Simple rope ‘bridges’ suspended high between trees are being erected to allow squirrel populations to reconnect with one another while avoiding the treachery of the roads. They are a prime example of how the city is seeking to reconcile urban life with nature.

The first such bridge was installed in Jette, while two years ago Uccle announced that it was building three bridges to reduce fatalities on busy roads.

Olivier Beck, a coordinator of species-oriented nature conservation at Brussels Environment, says squirrels use the bridges to saunter around the commune and into the woods to find family and forage for food. These connections matter for the bushy-tailed rodents. “Brussels was once a big forest,” he says. “For the squirrel, it was everywhere. But because of urbanisation, these habitats have become fragmented.”

Some species can adapt to the city, but others struggle to navigate the asphalt jungle, and their populations risk becoming isolated. “They become genetically very poor, and in the long term they will become extinct,” Beck says.

Animal bridges and tunnels

Thanks in large part to the Sonian Forest (Forêt de Soignes or Zoniënwoud), Brussels is blessed by nature. It boasts a relatively high level of biodiversity compared to other European cities of its size: some 38 percent of the Sonian Forest is located within the Brussels Capital Region and it has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2017 in recognition of the undisturbed nature of its primaeval beech trees.

However, the region has seen the loss of 180 higher plant species, 12 indigenous breeding bird species and four indigenous amphibian species, according to the Convention of Biological Diversity.

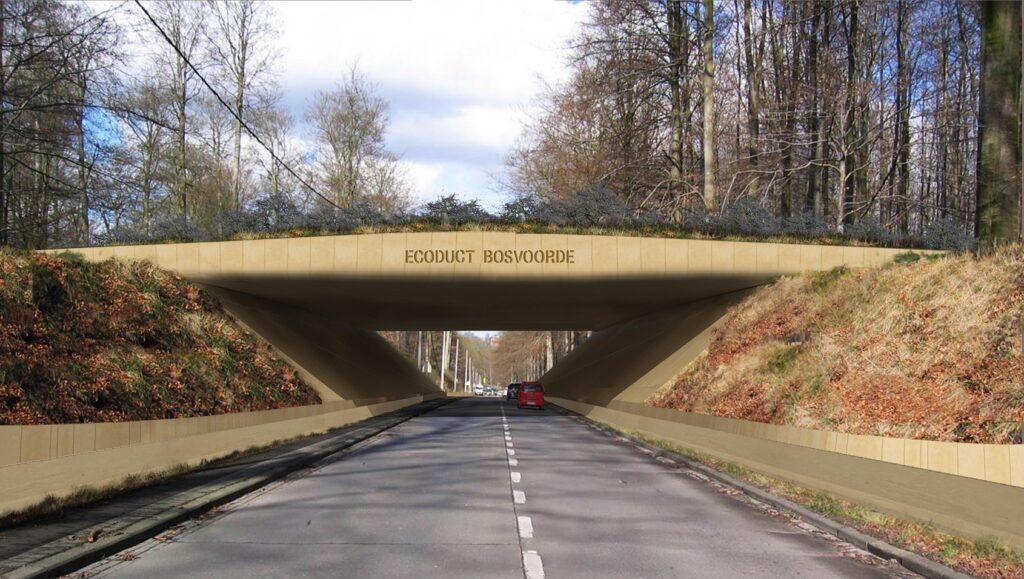

Brussels Environment, the public body responsible for the environment, in cooperation with partner organisations, is carrying out measures to stem this decline and protect native species. One such conservation measure is connecting populations by building tunnels and bridges known as ecoducts.

An ecoduct bridge in Bosvoorde

Cameras installed at the ecoducts in Watermael Boitsfort and Groenendaal have captured wildlife on the move, from large mammals, such as roe deer and wild boar, to insects and mice. “We have proof that it’s being used,” Beck says. “But it's too soon to tell if this new infrastructure is putting two isolated populations into contact and effecting genetic change.”

By the end of next year, a passage for cyclists and walkers to cross over the ring road from Groenendaal station to the Bosmuseum, the Priory Eco-recreaduct, is scheduled to be completed. This new green bridge is also expected to expand habitats for plants and small animals.

Authorities are ready to go further to protect native species, including the red squirrel, whose habitat in the British Isles has been taken over in vast swathes by the more aggressive and invasive grey squirrel. Beck says that Brussels Environment is prepared to capture and euthanise any grey squirrel that might appear in the city.

Street parakeets

Such a clear management plan, however, is no longer possible for other high-profile invasive alien species – namely, the three types of parakeets, whose luminous green plumage brightens up the city: the ring-necked parakeet (Psittacula krameri), Alexandrine parakeet (Psittacula eupatria) and the South American monk parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus).

A perroquet nest

The first two species are similar in appearance and behaviour, often flocking together, although the ring-necked is the more common and has been observed in Brussels since the 1970s. Experts are unsure whether the first individuals were released or escaped, with one view being that they came from the former Meli Zoo in Heysel/Heizel. While the first two species build their nests inside tree cavities, the monk parakeet constructs its large nests in the branches.

The first two species also gather in their thousands in big dorms in Brussels, "so it’s quite easy to count them to have an estimation of their population evolution", says Beck. "The graphs show an amazing increase in the population before a plateau. It’s a good example of a population explosion. In the 1970s you had 50 to 100 and it quickly went to 10,000 to 15,000. We think now there’s a kind of saturation, but we’re not sure."

Beck regrets that the parakeets were seemingly welcomed initially as something exotic. "It is problematic for endemic species because every cavity they occupy in a tree cannot be occupied by native species, who need the cavities as well,” he says.

While there is not yet clear scientific evidence of an adverse effect on bat or bird species, Beck says the impact is obvious. "A lot of scientists like me say that you don’t have to wait until the negative impact is proven,” he says. “You have to act already now, or at the beginning of this distribution phase when it’s feasible to do something. If you wait until it’s proved, then maybe it’s too late – the population will be too big. And that’s what’s happened with this parakeet; we waited for 30 of 40 years...We already tried to capture them, but we didn’t succeed, so for me it’s lost. It’s an example of bad management."

By contrast, Beck highlights actions to support house martin populations in the city as a success story. The birds commonly construct nests in the outer walls of buildings under the eaves, and Brussels Environment has installed artificial nests to support such colonies and boost the overall population. The intervention, which began in 2003, working alongside NGOs and the building owners, led to a steady uptick in numbers.

Brussels Environment also employs experts from the conservation NGOs Natagora and Natuurpunt as “nature facilitators.” These experts are hired to respond to calls from members of the public on how to ecologically manage their gardens – Beck calls them “a kind of garden architect” – who might, for example, advise on where to build a small pond, install beehives or hang up nesting boxes for birds.

Beck's favourite biodiversity hotspot is the source of the Vuylbeek, a small stream in the Sonian Forest. "The water is perfectly clear and the biodiversity is therefore high," he explains. "Another little valley comes together at this spot, and when you’re walking around here you will find top nature!"

Bat to the future

The bat is another animal whose numbers are growing thanks to conservation efforts, with Brussels home to some 20 bat species. "Bats adapt much more than we think, and we really come into contact with bats everywhere in the Brussels region," says Claire Brabant of Wallonia and Brussels nature protection NGO Natagora.

Brussels is home to some 20 bat species

However, she acknowledges that some colonies in dwellings pose problems, such as guano on windows and even sneaking into habitable rooms, but she insists that solutions for limiting or avoiding nuisance are always available. “A few known colonies in the Brussels region show that cohabitation with humans is now going very well," she says.

Organised viewings of the once-hated animals are regularly held in the city. "We often take part in the bat night at the Rouge Cloître where the general public is always amazed to see so many bats. In general, people like bats and are not afraid of them; there has really been a change in mentality in recent years."

Flying bat

Alert walkers in the Sonian Forest may have spotted one of the most common conservation actions, the installation of bat boxes in trees. Additionally, orange LED streetlights were installed in Jette as part of the Bat Light District conservation project. Traditional white lighting made bats easy prey for raptors.

Perhaps surprisingly, bats are also benefiting from the bridges and the ecoducts: they use the infrastructure to help navigation and a way of overcoming the barrier presented by the ring road around Brussels.

Seeing the Senne again

It is not just animals that are recovering but the wider natural environment. The Senne River, which runs through the centre of Brussels, was once highly polluted and prone to flooding. The river was almost entirely covered between 1867 and 1871 under the city’s then mayor Jules Anspach, who lends his name to the large central boulevard created during this reconstruction. But with the completion of two new water purification stations this century, the Senne is no longer part of the sewer system and efforts are being made to ‘renature’ stretches of the river.

The success of the recent restoration of the river alongside Boulevard Paepsem has surprised even the project’s leaders. Anna Roose from Brussels Environment says colleagues overseeing the renaturing had not anticipated the speed with which nature would reclaim the area. While formal monitoring has yet to be carried out, Roose says that ongoing observations offer a promising picture, with common sightings of moorhens and coots, along with the occasional kingfisher and cormorant, “a strong indicator that the fish stocks are in good condition.”

These Paepsem actions, which were carried out under the EU’s programme for nature conservation called LIFE, were completed in 2019. They are part of the LIFE Belini project, which also focuses on water quality in the Dyle and Demer rivers and aims to further coordinate conservation efforts between Flanders and Wallonia.

Roose says that opening up the Senne in urban areas serves two main purposes: it increases biodiversity by bringing oxygen and light into the water and renaturing riverbanks, and it improves the quality of life of local residents. “We know that water and nature have a calming effect on people,” she says. The attractive pathway along the Paepsem stretch is much used, and the city’s approach is to dedicate one bank to recreational purposes in all areas where conservation actions are taken.

The Senne after its opening

Furthermore, creating such green areas is a common measure for alleviating the urban heat effects, whereby pavements and buildings absorb and retain heat. She also hopes that the actions can raise environmental awareness, although she notes that reviving habitats for endemic species can also benefit invasive alien species, among which Japanese knotweed and crayfish appear to be thriving. Brussels Environment is the lead coordinator of a separate LIFE project that aims to tackle such non-endemic species in the Senne as well as other rivers in Belgium.

Additional planned measures include reconnecting the Maalbeek tributary, which is currently flowing to the sewage system, and removing barriers to fish migration from the Senne and the Woluwe tributary. “We need to enlarge areas where fish thrive so that when there is a bad quality water in one area they can move to an area where the water is better,” she says.

In 2021, a stretch of the Senne north of Brussels was also restored, although the land is privately owned and not open to the public. Roose says Brussels Environment is exploring possibilities for further opening up of the river despite the challenges presented by a lack of space or the political will to do so.

The next reopening is likely to be a section through Maximilien Park in the north of the city, although Roose says that the cost is likely to exceed initial estimations and it is not certain when the works will start. The possibility of creating light and aeration points in the Senne vaulting at more central points is also being investigated, according to Roose. “Being able to see the Senne through glass would be a great way to make people aware that they have a really nice river flowing under their feet!”