Commissioned by the Club of Rome to a team of MIT researchers, the alarming Meadows report on The Limits to Growth was published fifty years ago. Countless events were organized throughout the world to celebrate the anniversary. One of them took place this October at Belgium’s Royal Academy and made me discover a letter I found truly amazing.

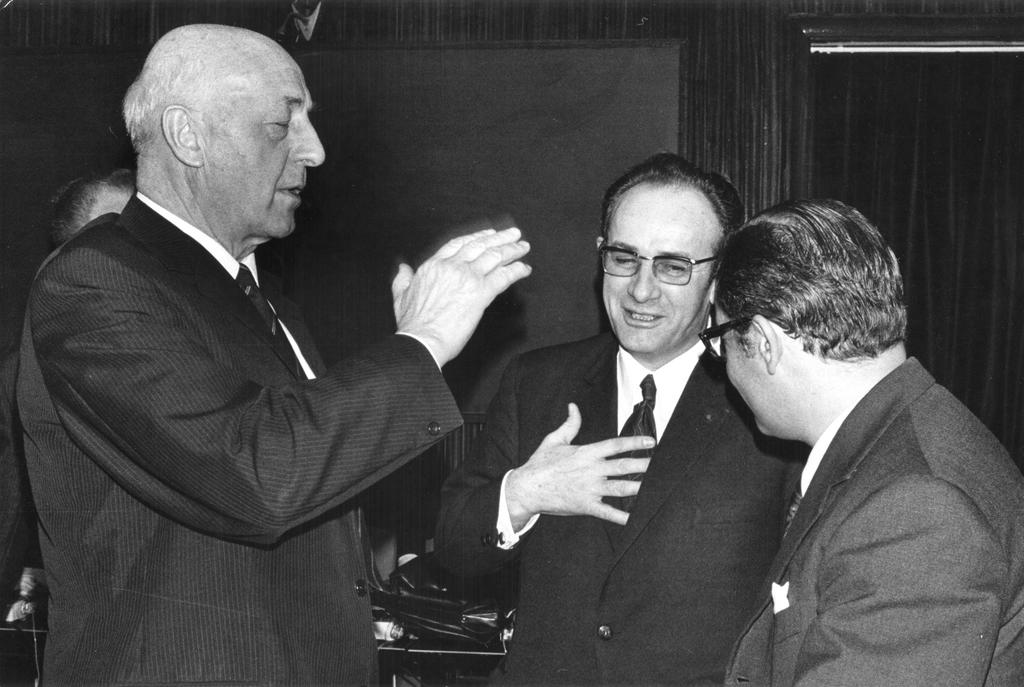

The letter was written in Dutch in Brussels and dated 9 February 1972, three weeks before the publication of the Meadows report. It is available online in both the original Dutch version and a somewhat defective English version. Its author is the then European Commissioner for agriculture Sicco Mansholt and the addressee is Commission president Franco Maria Malfatti, whom Mansholt was about to replace in March 1972 until the end of the legislature in January 1973.

While not officially published, a draft of the report had already been presented at international meetings in Moscow and Rio. Mansholt had read it and was manifestly shaken. “It is clear”, he wrote, “that policy must be radically redirected”. Why? Fundamentally because of world population growth. “Our duty is to point to economic action which can help in limiting births”, by example through “the abolition of assistance for large families”.

If world population could be stabilized, some equilibrium might be found according to Mansholt on condition that we gave priority to food production, sharply reduced the per capita consumption of material goods, stopped producing non-essential goods, lengthened the life of all capital goods, and redirected investment towards recycling and the reduction of pollution.

But since it is over-optimistic to suppose a stable world population, “far more radical political measures” may need to be adopted and the “established social order” of private enterprises may need to be given up. As state socialism offers no solution either, we may have to turn to something like “strongly central planning combined with largely decentralized production”.

What was certain for Mansholt was that “we should stop directing our economic system to the search for maximum growth and a constant increase in the gross national product”. He therefore suggested replacing GNP by what he called (in French) “bonheur national brut” (gross national happiness) following fellow Dutchman and Nobel economist Jan Tinbergen. In order to address the ecological challenge while “satisfying the fundamental demand of justice”, the European Commission should draw up a “European central plan” that “no longer aims for the highest possible GNP but takes as its cornerstone the bonheur national brut”: “Even if a greater public care for people’s spiritual welfare were to require a higher GNP, we simply no longer have that option, because ecology and the need to preserve enough sources of energy for future generations will be the deciding factor.”

Mansholt gave some concrete examples of the policies he had in mind. In order to lengthen the life of cars, they should be “subjected to heavy taxes in the first five years of their life, followed by a reduction in the taxes for the next five years and finally no taxes”. Non-essential goods should be “taxed very heavily”. The focus of scientific research should be “switched from growth to well-being”. And the disruption of the ecological balance by pesticides and insecticides must be stopped. As the implementation of such a programme would obviously involve a sharp increase in costs, Europe’s common market (then comprising six states and expected to be imminently joined by four more: Denmark, Ireland, Norway and the UK) would “need to be protected against external influences”.

These are just a few illustrative policies, Mansholt wrote at the end of his long letter. But he would “regard it as highly desirable that the Commission should focus on these questions in the final year of its mandate so as to be able to make well-founded proposals to the Council”. He made no attempt to examine “the means of making this type of policy acceptable to public opinion. This task is one for the political parties rather than the Commission.”

This was February 1972. One cannot say that this message was heard either by the Council or by Europe’s political parties. When, in June 1972, the French magazine Le Nouvel Observateur organised a big meeting in Paris around the Meadows report, André Gorz, Herbert Marcuse, Edgar Morin and other major thinkers who were destined to help ignite Europe’s ecological awareness took part. Sicco Mansholt, apparently, was the only political personality who bothered to attend, much to the disapproval of many of his peers, from the communist left to the neo-liberal right.

Yet he was the clear-sighted one. Long before climate change made the global ecological challenge even more daunting, his half-a-century-old letter lucidly sketched the rough contours of the European Green Deal that is now quasi-unanimously regarded as long overdue and that Mansholt’s compatriot, Commission vice-president Frans Timmermans is trying hard to turn into reality. Ground for hope? Or for despair?