Ahead of the International Holocaust Remembrance Day on 27 January, Yad Vashem in Jerusalem has launched an exhibition about Jewish families who survived under assumed identities in Nazi-occupied Europe, including in Belgium.

The day marks the anniversary of the liberation of the extermination camp Auschwitz-Birkenau by the Soviet Red Army on 27 January 1945.

The exhibition by Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre, tells the stories of 14 families and is based on documents from its archives and material from collections such as personal documents, testimonies, and photographs. The forged documents, if they remain, were donated to Yad Vashem by survivors and their families.

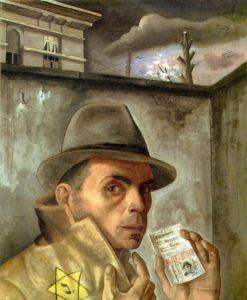

In a famous self-portrait by the Jewish-German painter Felix Nussbaum (1904 – 1944), he is seen holding an ID-card stamped with “Juif-Jood”. He stands, cornered against a wall and with dark clouds above, with a hat on his head and the yellow Star of David on his coat, looking straight into the eyes of the viewer, defying the Nazi persecution.

His life is closely linked to Brussels. In 1942 – 1944, he and his wife were hiding in an attic of a building at rue Archimède 22, until an informer tipped the Nazis about them and they were deported to their death in Auschwitz. They never received any Belgian identity cards and it is not known if they had any false papers.

Self-Portrait with Jewish Identity Card, around 1943, Felix-Nussbaum-Haus Osnabrück, Leihgabe der Niedersächsischen Sparkassenstiftung © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

Throughout the Holocaust period, in the shadow of persecution at the hands of the Nazi regime, Jews tried to save themselves and their families using forged papers that provided them with false identities. For many, this was a daily battle for survival in a hostile environment, which required resourcefulness and the ability to adjust to constantly shifting circumstances.

"I often used to wake the children in the middle of the night, to check if they remembered their new names even when half asleep. I would repeat over and over again that no one could know that we were Jewish," tells Brenda Pluczenik-Schor from Krakow, who survived the Holocaust living under a false identity in Budapest together with her husband and daughters.

In many cases they were helped by non-Jews, some of whom were paid for their services. Others offered assistance for no monetary gain and at risk to their own lives, eventually being recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations.

For children, living in fear and separated from their parents, it was often traumatic. If they were hiding in Christian institutions, they had to memorize other prayers and renounce their religion and mother-tongue, trying to erase all signs of Jewish identity.

The Birnbaum family in Belgium survived in hiding for two years in the small village Godinne sur Meuse, today part of Yvoir commune near Dinant, where they happened to find an apartment for rent at the house of Joseph and Leonie Morand, an elderly couple who lived on the ground floor.

Originally from Poland, they lived in Antwerp, where their two children grew up. After the Nazi-German invasion of Belgium, they fled to France. The father in the family managed to escape to England but the rest of the family had to return to Antwerp. When things got worse there, the mother managed to obtain false papers of poor quality for herself and her sister-in-law.

With false papers for only two of them, the family of six – mother Hudes, sister-in-law, grandparents and the two children, Henry aged 10 and Charlotte aged 5 - lived in hiding in the village in 1942 – 1944, until the liberation of Brussels in September 1944, when they returned to live there. After the war, the family was reunited and eventually moved to England.

In 1982, Joseph and Leonie Morand, were posthumously recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations. In the village, the Birnbaum family twice narrowly escaped a search by German soldiers who were garrisoned nearby. Told by his friends to evict the Jewish family, Joseph Morand refused. “The good Lord sent them to me, I’m not going to throw them out”.

Charlotte, who now lives in Israel, told The Brussels Times, that people in the village were aware that Jews were hiding there and that someone must have informed the German garrison. “The soldiers didn’t really know how many we were and didn’t search the rooms in the house,” she recalls. “My grand-parents were ill and in bed and we children were hiding under their beds.”

During their stay in the village, they did not go to school but she remembers going out to play with the other children in the village. Her brother was more afraid of leaving the house. She grew up with Yiddish as her main language but knew also Dutch and French and understood German. After the war, they were frequently in contact with the Morand family and used to visit them.

This year, on 27 January, the European Commission will for the first-time light the Berlaymont building, the Commission headquarters in Brussels, with a projection of #WeRemember. Because of the pandemic, most remembrance events will take place online. There will among others be a statement by Commission President von der Leyen on the same day.

The President will participate together with Vice-President Schinas, Commissioner for Promoting our European Way of Life, in a commemorative online event organized by the European Jewish Congress on 26 January. Vice-President Schinas will also attend in person in commemorative events in Athens and in Thessaloniki on 27 and 28 January.

M. Apelblat

The Brussels Times