On the morning of 1 February 2020, the UK woke up with a hangover after the Brexit crusade finally ran its course and Britain left the European Union. But what some hailed as the end of a long battle was really only the start of a far longer campaign. Three years on, what's become of Brexit?

Despite now standing apart from the EU, the debate about Britain's relationship with the bloc rages on. The nation remains divided and relations with Europe are still raw. On Tuesday, the IMF announced that the UK economy will fare even worse in 2023 than sanction-hit Russia.

Not all of this is down to Brexit, but it hasn't helped. British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak is unfazed: "We’ve made huge strides in harnessing the freedoms unlocked by Brexit to tackle generational challenges," he maintains.

Just what these freedoms are is less clear. As things stand, the lives of many who identify with both Britain and the EU have become unnecessarily difficult. Whether sending or receiving packages, passport checks or a new €7 EU entry fee from autumn 2023, the barriers can't be ignored.

Many Brits in Belgium and elsewhere on the continent have been frustrated by the friction between the British islands and the mainland.

Traffic jam at the Channel Tunnel Eurotunnel, in Calais, France, Friday 04 December 2020. Credit: Belga / Benoit Doppagne

In the UK itself, Brexit tensions fester unabated and public discontent is reflected in polls. The Conservative Party that set the solitary course now faces electoral oblivion in 2024, with some polls putting Labour at around 50% and the Tories at 25% of the vote. 67% of Britons polled by YouGov on 5 January 2023 believe the government is handling the UK’s exit from the EU “badly”.

The £10 billion hole in the economy

The economic consensus on Brexit is catching up with the political outlook. Brexit is costing the economy £10 billion, Bloomberg Economics reported this week, as British companies struggle to attract investment and hire workers.

Exclusion from the single market has driven a steep decline in trade – trade with the EU has fallen 16% in the UK to EU goods trade, and by 20% in trade from the EU to the UK.

The deficit comes with a diminished standing on the global stage. Whilst Brexit proponents were vociferous about the UK being able to assert its independence as an economic and political force to be reckoned with, exclusion from the EU has pushed Britain down the pecking order when it comes to trade with major economies such as the US.

Washington’s controversial Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) will subsidise US-based business, possibly triggering retaliatory measures on the EU side. In a worst-case scenario, the UK could find itself caught in a trade war and outside of both markets.

UK labour shortages

Losing access to the single market has also provoked a labour shortage, driven by the fall in EU migration to the UK.

In particular, the accommodation and food services industry currently has a 35.5% shortage in workforce; the construction industry 20.7%. Healthcare and social work have also seen record vacancies in September-November 2022 with 208,000 unfilled positions.

British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak serves breakfast at a homeless shelter in London. Credit: Flickr / Simon Dawson / No 10 Downing Street

Most industries complain that their imports and exports to Europe have gone up in price, eating into margins and making some businesses untenable.

Despite staunchly pro-Brexit publications asserting that “cutting ties with the EU has allowed Britain to create freeports to spur trade and reform financial services”, experts believe that freeports open the door to criminal exploitation for money laundering and illicit trade.

Diminished cultural clout

Just as Britons cannot live, study and work in the EU, British universities have seen a sharp drop in EU students, whose numbers halved post-Brexit – particularly as many universities in Europe now offer courses in English which are cheaper and more accessible.

EU students must now have to pay exorbitant fees to study in the UK: around £35,000 for an undergraduate programme (depending on the institution) and without financial support.

Belgian Princess Elisabeth walking in front of the Fond Quad in Lincoln College at Oxford University. Credit: Palais Royal Bruxelles / Belga

This paywall undermines Britain's cultural influence in Europe. The British music scene has been crippled by former PM Boris Johnson’s no-deal Brexit, which saw a 45% decrease in UK musicians booked to play European festivals. British band White Lies were forced to cancel their first European tour date in April last year after their equipment was held up in customs.

"It’s very frustrating when… your equipment has been stuck in a 25-mile queue on the M20 through no fault of your own, and no fault of the trucking company either,” drummer Jack Lawrence-Brown told the NME.

Bregretful?

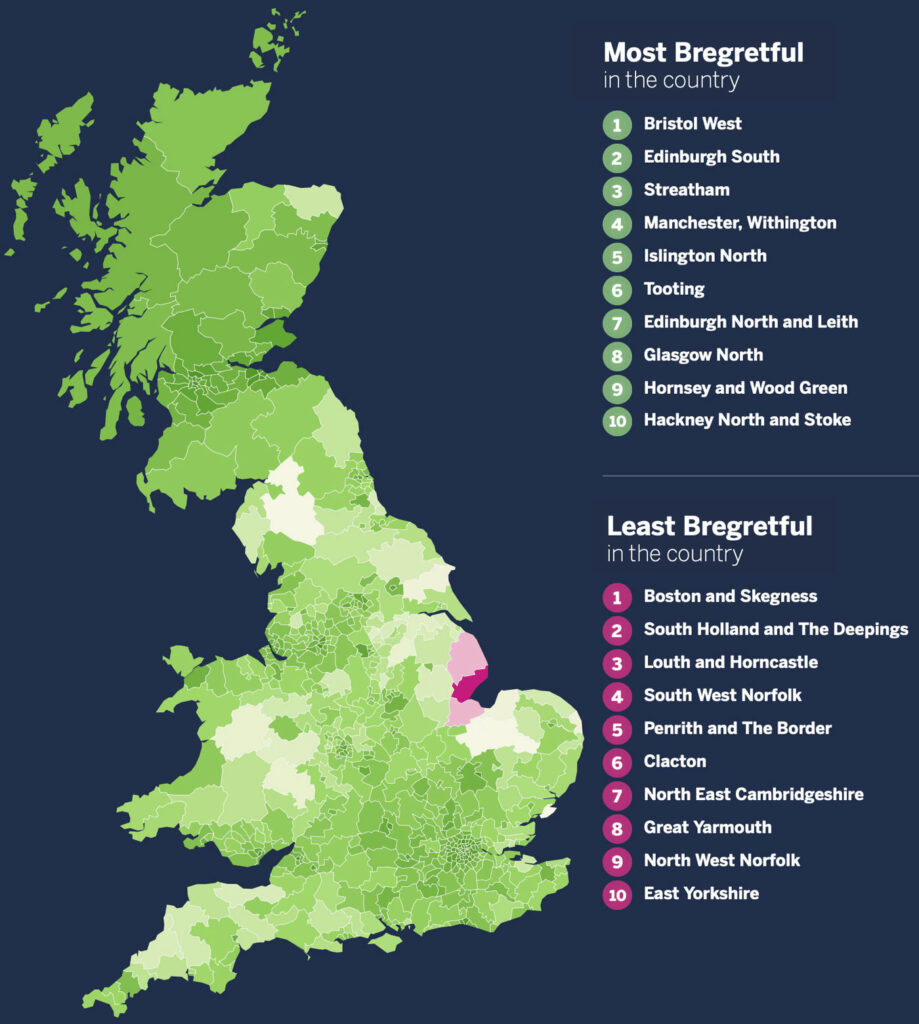

Is there a way back into the EU for the UK? The tides have turned in British opinion polls with research released this week by UnHerd indicating that "all but three of Britain’s 632 constituencies" now agree with the question “Britain was wrong to leave the EU.”

Credit: UnHerd

Despite this, the opposition Labour Party is resolute on the matter and refuses to reignite the Brexit feud, fearing it could only damage Labour’s election chances. Besides, Labour benefits from the ongoing flow of Brexit failures, which play against the Conservative government and into their hands.

“We’ve left the EU now and there is no case for going back in,” Labour leader Keir Starmer said in response to Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, who criticised their Brexit stance.

The UK united no more?

Both Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain, with the leave vote being secured by residents in England and Wales. As Westminster's political turmoil continues with little consideration for Belfast or Edinburgh, the UK risks falling apart.

London's attitude to Brussels has also shown little diplomatic fibre and the Northern Ireland issue remains the priority for EU officials. Any resolution (or otherwise) will be the basis of future UK-EU relations. But many are pessimistic, especially after the UK Government tore up the NI Protocol in the negotiated EU withdrawal agreement.

While the current UK Government does all it can to deflect blame for the nation's troubles, their descent in national polls indicates that Brexit's political capital is running out. Yet concrete solutions require honesty about the problem.