On Thursday Scientists at the VIB-KU Leuven Center for Brain and Disease Research announced a landmark discovery in Alzheimer's disease.

"We solved a question that has been hanging around for decades – which is why we lose brain cells when we get Alzheimer's disease," Bart De Strooper, Belgian molecular biologist and co-author of the study published in the journal Science, told The Brussels Times.

There is currently no cure for the disease which has become one of Belgium's leading causes of death.

What causes cell death?

The study found that when amyloid plaques (extracellular deposits of misfolded proteins) accumulate in the brain, cells react by disappearing – a sort of suicide, also called programmed cell death.

"It's a normal process, and sometimes it's a good process – like when there are too many cells, and some decide to remove themselves," De Strooper explained. "But here you have a pathological situation where they remove themselves when they shouldn't. And we found that mechanism."

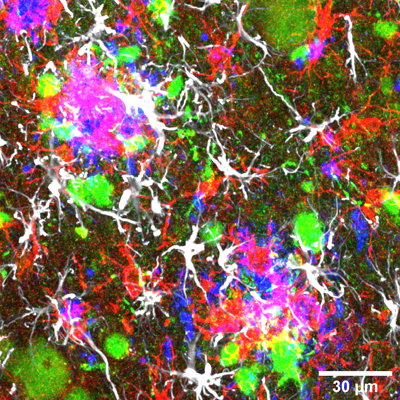

Image displaying transplanted human neurons (green) and mouse neurons (red and white) in a mouse expressing amyloid plaques (blue). Credit:VIB-KU Leuven Center for Brain & Disease Research

The amyloid cells trigger a specific gene's up-regulation (in simple terms, the higher production of activity). The down-regulation of this gene, conversely, kept the neurons from dying.

Earlier this year, another study reported that the removal of amyloid plaques from the brain with antibodies helped Alzheimer's patients, but it was still unsuccessful in curing the disease completely.

Potential medication

"We need therapies that go beyond amyloid removal," De Strooper stressed. And now that scientists have further understood the cause of neuron cell death in Alzheimer's patients, the world is one step closer.

Researchers Bart De Strooper and Sriram Balusu. Credit:VIB-KU Leuven Center for Brain & Disease Research

"We could potentially make medication that blocks the neural cell death," the molecular biologist continued. "We could take different drugs from the shelf and make the perfect combination for treating the patient." Which, he added, is already used in cancer treatment.

Pharmaceutical companies are paying attention. De Strooper says that they were contacted by an American biotech company interested in the potential for development that could result from their research. The company plans to send some of its formulas to be tested in the Belgian team's research.

"That's the way these things go. You need to look at research not as a miracle, but as a series of small steps forward. Then you combine all these steps and all of a sudden you realise that you made a lot of progress, and that's exciting," De Strooper said enthusiastically. "Our paper is one of many interesting papers, and it all brings us to a better understanding of the greater puzzle."