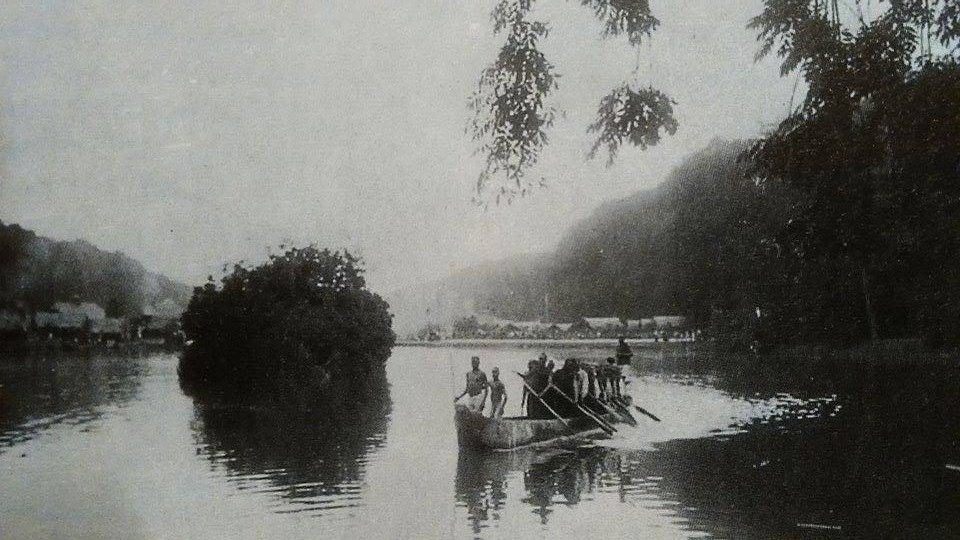

The year is 1897. We see three African tribal villages. In and around several wooden huts with straw roofs, men, women and children are carrying through their daily tasks. Occasionally they perform dances and play the drum. There is a small lake adjacent to them. Weary African men are circling the waters around a tiny island, but they are not fishing nor guarding anything. The weather is mild for the time of the year, and there is a cool breeze. From time to time, some men dive into the water. On the shores, well-dressed white men and women are gazing and throwing a few coins into the deep…

We are in fact at the International Exhibition of 1897 in Brussels. More precisely, we are about 10 kilometres east of the city. We took the tramway close to the Cinquantenaire Park (Jubelpark) at the Brussels main exhibition area and headed to the Colonial Exhibition in Tervuren.

The ride (today tram 44) followed a scenic avenue and was an attraction in itself. The wide Avenue de Tervuren, with its double tramway, was specially built for the occasion on orders of King Leopold II of Belgium. They led straight to the also newly-built Palais des Colonies, where the King was proudly highlighting some of the colonial assets of his Congo Free State in Central Africa.

In the halls, we get to see indigenous art, ethnography, geology, a diorama, a greenhouse, an ichthyology room showcasing tropical fish, and maybe even more importantly for Leopold: export products, like cacao, rubber and tobacco. The King hopes that his “humanitarian project” in Central Africa becomes more popular with the Belgian government and people.

Billboard of the International Exhibition in Brussels (1897)

On the grounds outside, we see the ethnological exposition in three newly built “tribal” villages, where 60 imported African people are living during the day and instructed to “act indigenously”. This kind of “attraction” was very popular in its day in the Western Hemisphere. It was neither the first, nor was it the last. However, it was due to this “human zoo” that this specific World Exposition became infamous.

The exhibition itself was not criticized but because seven members of the delegation of 276 individuals from Congo Free State – officially part of a “diplomatic mission” – perished due to colds and flu, only dressed in their traditional garments. In fact, in Belgium, these “human zoos” in the form of Congolese villages, also took place in the 1885 and 1894 exhibitions in Antwerp. Because of the previous human tragedy, a “light” version also took place at the Expo ’58 in Brussels, just south of the Atomium.

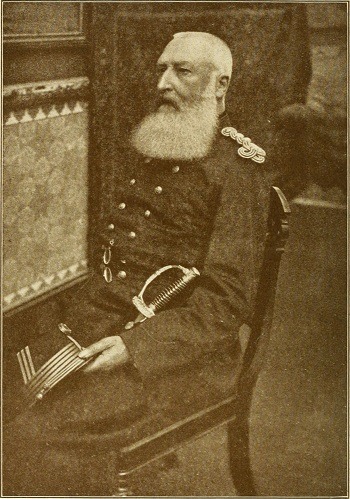

The government of Belgium never backed King Leopold II (1835-1909) for the creation of his Congo Free State. It started as a strictly personal endeavour by the King and became his “private property”, where he reigned as its sovereign. Notwithstanding, the Congo Free State was recognized internationally in 1885.

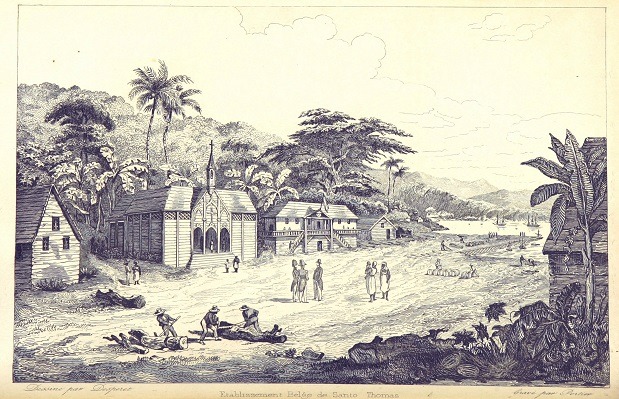

However, it is much lesser known that his father, King Leopold I (1790-1865), already supported colonial aspirations of businessmen and private companies, resulting in projects in Central America between 1830 and 1854. They were backed by the Compagnie Belge de Colonisation, until its financial demise in 1854 due to lack of profits.

Early Belgian agricultural settlement in Santo Thomas e Castillia, Guatemala (1843 - 1854). King Leopold II's father, Leopold I (1790 - 1865) already supported colonial aspirations of businessmen and private companies during his reign, resulting in projects in Central America between 1830 and 1854.

When Belgium was established in 1830, it found itself literally surrounded by colonial powers, not only the Netherlands, but also by Great Britain, France and Germany. Belgium, as a young nation, felt that it also needed international trade markets and vast agricultural lands. In this way, the country hoped to solve its precarious economic situation in the 1840s – although it was a pioneer in rail networks, having established the first railroad on the European continent (Brussels-Mechelen) and a leader in manufacturing, creating the steel mills in Liège. However, these earliest Belgian endeavours in Central America proved unsuccessful in the long term and did not result in permanent (agricultural) settlements or colonies.

King Leopold II: “Belgium needs a colony“

From the 1850’s on, the eldest living son of King Leopold I, the Duke of Brabant (King Leopold II since 1865) showed an interest in amassing a personal fortune through international trade. He travelled a lot and visited the British and Dutch colonies. He had been urging Belgian politicians for years that their country “needed a colony“.

But his efforts were strongly opposed by the government filled with Catholics and Liberals, who felt a colonial project did not align with their political beliefs. And they had not forgotten the huge financial losses of the earlier colonial enterprises. Belgium, as a neutral nation, also had to maintain a careful stance among the leading powers in Europe.

Leopold II was intrigued by a work detailing the colonial system in the Dutch Indies, titled Java, or: How to Manage a Colony, published by the fittingly named author J. W. B. Money in 1861. Profits from local production were used for the development of railways and canals in the Netherlands.

Leopold II believed that the still-young nation needed grandeur, wealth and a place among the other powers, with him as mediator and benefactor. He studied almost fifty possible colonies. Author Adam Hochschild described him, in his well known book King Leopold’s Ghost (1998), as a ‘sly fox‘ whose perceived early philanthropy was just one of his ploys towards fulfilling his personal greed.

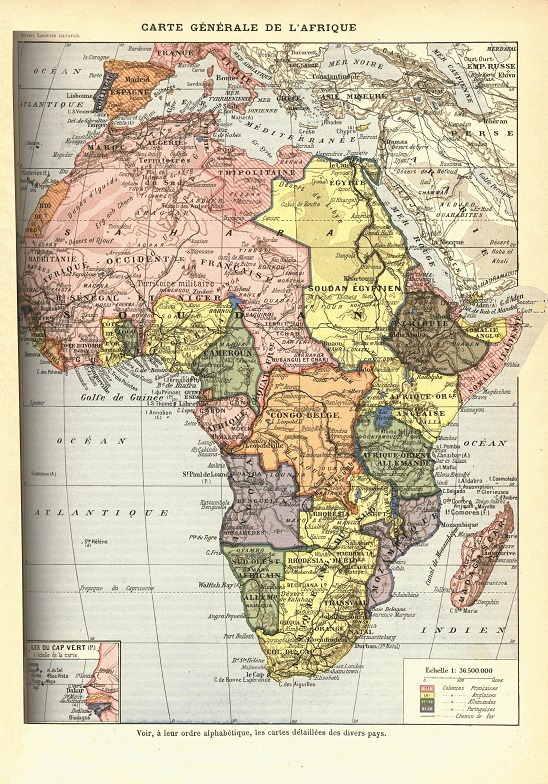

Map of Africa, 1898, marking the regions according to how the European colonial powers had carved them. Yellow - English, Light pink - French, Green - Germans, Purple - Portuguese. Orange - Belgium.

Much later, Leopold II was firmly remembered as the “King Builder“. He had personally financed and/or ordered (just to name a few projects): the development of the city of Brussels and its wide avenues (inspired by the city of Paris), the expansion and building of royal palaces, the Royal Greenhouse, the Japanese Tower and Chinese Pavillion, the Cinquantenaire Park (1880) with its triumphal arc, the Palace of Justice (1883), parks, churches and art museums.

In Antwerp, he commissioned the expansion of the Zoo and ordered the building of the monumental Antwerp-Central Railway Station (1905). In Oostende, his favourite city on the Belgian coast, he ordered the building of the Royal Galleries (reminiscent of a mirrored L – his royal seal), and the Hippodrome Wellington.

But first, the King needed financial backing for these projects. And lots of it.

A King ahead of The Scramble for Africa

In the 1870s, Africa was still the “dark continent”, not fully explored and thus largely unclaimed by the big colonial powers. A change (and a chance) was at hand. Leopold II was familiar with the published adventures of the journalist and explorer Henry Morton Stanley, who went to seek the missing Dr. Livingstone in Central Africa in 1871-1872. Leopold also knew Stanley’s resulting book How I Found Livingstone.

His eyes must have sparkled, reading about this unstoppable explorer in the heart of a vast and unexplored continent. Between 1874 and 1877, Stanley was commissioned to participate in a second exploration by the New York Herald and the British Daily Telegraph to further map the geography of Central Africa.

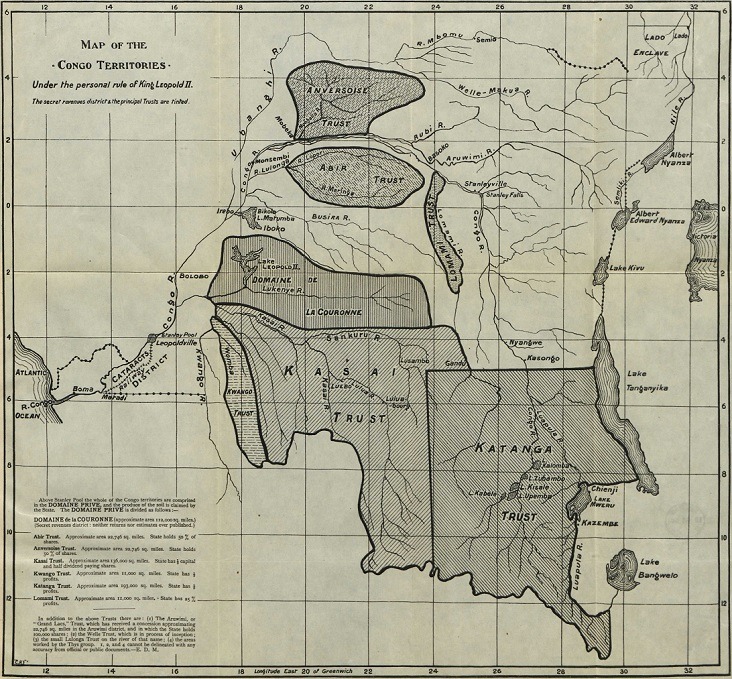

Map of the Congo Territories, under the personal rule of King Leopold II

In September 1876, Leopold II, privately and without the consent of his government, organised an international geographical conference (known later as the Brussels Geographic Conference) in his Royal Palace in Brussels. He brought together 40 Belgian and international geographers, politicians, philanthropists, missionaries and famous explorers. They aimed to establish an international coordinated effort for a “geographical exploration of Central Africa and to end the slave trade”, thus giving it a philanthropic veneer. The explorer himself, who turned out to be the most important person for Leopold’s plans, was absent from this conference. Stanley was still crossing the heart of Africa, but Leopold was carefully reading his articles published jointly by the American and British newspapers.

The conference led to the birth of the Association Internationale Africaine (AIA for short). The King was to be the chairperson and the only stockholder in the company. At its sole meeting, it adopted a flag: a golden star on a blue field. When Stanley returned in 1877, the British government was not interested in any new enterprises. But Leopold II was.

In 1878, Leopold II had founded a new organization, the Comité d’Études du Haut-Congo. It aimed to study “the private exploitation of the Congo basin”, the second longest river in Africa. In 1879, it was superseded by Leopold’s Association Internationale du Congo, which aimed to set up trade posts around the Congo River and to buy land. This expedition was led by Stanley in 1879-1884 under the flag of the AIA, whilst in fact he was in the service of Leopold, secretly establishing treaties (over 400) with local rulers for the King personally and not in the name of any government.

King Leopold II of Belgium, who ruled over Congo Free State, which he considered as his "private property".

From 1884 to 1885, the Conference of Berlin was held, with the aim of resolving problems following the international “scramble for Africa”. Leopold did not personally attend. However, the AIC was recognized as a state by all the 15 participating European countries and the USA, to be followed reluctantly by Leopold’s homeland as the last country to do so. In May 1885, the AIC became the État indépendant du Congo, the Congo Free State. Leopold promised free trade, humanitarian projects to civilise the country and end the slave trade.

The resulting Congo Free State (1885-1908) was not a colony of Belgium. It was the private property of Leopold II. The only bond between Belgium and Congo was the name of their shared ruler. The first ten years of the Congo Free State cost Leopold massive amounts of money to personally fund his colonial project. Large parts of the country were still unmapped jungle. Inland there was still fierce opposition from tribal kings, Muslim rulers and slave hunting gangs like Tippu Tip’s in the east.

Congo Free State: A terror regime

By this time, Leopold had already spent vast sums on his organisations, buying out the stockholders, and on propaganda. The Belgian government did not allow direct financial or military ties with Congo. During the first five years, the King was repeatedly wavering between bankruptcy and lifesaving loans from bankers and the Belgian government itself. They could not let their King go bankrupt.

Despite a government loan in 1890 of 25 million Belgian francs, bankruptcy was still a threat. The cost of building a basic governmental apparatus, roads and railroads was skyrocketing. Luckily for Leopold, around the same year wild rubber was discovered. Rubber was needed by the newly born automobile industry. This natural product would make Leopold’s financial problems disappear as melting snow.

To maximize revenue, Leopold decreed that land that was not inhabited or cultivated was now property of the state. More so, Africans could only sell their harvested products to the state, at the fixed price set by the state. This violated the promise of free trade that Leopold II had made to the Berlin Conference. However, there was no reaction from the other powers.

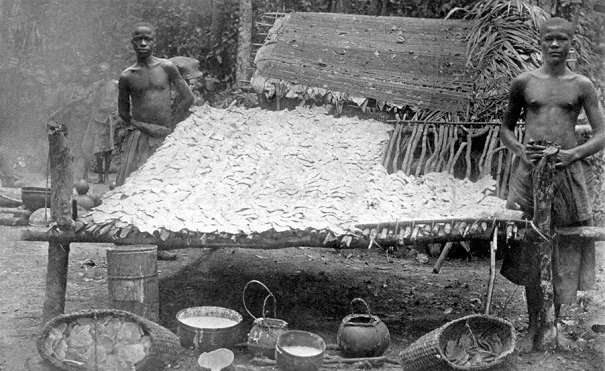

Villagers in Leopold II's "Congo Free State" had set quota of rubber production that was due for collection every 14 days.

In 1892, the lands that were deemed “vacant” became part of a domainal system. Large parts of the state became concessions and were exploited by private companies. They imposed a heavy “tax” on all the inhabitants, forcing them to collect ivory, rubber or other valuable products, since currency was deliberately almost non-existent.

Two of the most well known concession companies were the Anglo-Belgian Indian Rubber Company (ABIR) and the Société Anversoise du Commerce de Congo. Leopold owned 50 % of ABIR. When ABIR settled a trading post with an agent and guards, all African men in the area were counted. And a tax of eight kilos of wet rubber every 14 days was imposed on everyone. The state armed the agents and their helpers. They received a bonus if they could bring in more. Leopold was repeatedly pressing ABIR to keep maximizing the rubber harvest. Only a few years later, there was barely a drop of rubber still to be found. The forests had been sucked dry.

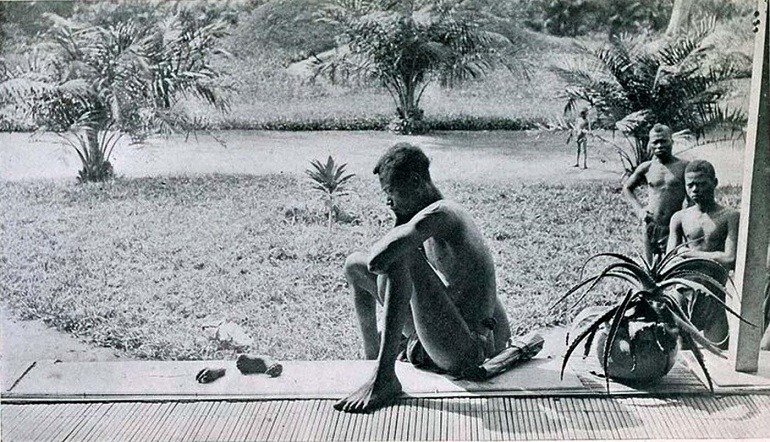

For years, the indigenous people were punished harshly for not meeting their rubber quotas. Failure to do so was met with severe beatings with the chicotte, rape or even worse. To replenish their ammunition, Leopold’s agents had to bring a severed right hand. This was to prove they had deemed it necessary to take someone’s life and the bullet was not just used to hunt valuable animals.

A Congolese man looks at the severed hand and foot of his five-year-old daughter. He had not met the rubber quota so militia from the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company punished him. Leopold II was 50% shareholder in the rubber company and pressed them hard to maximize the rubber harvest.

The visual image of Leopold’s cruel reign was born: the severed hand, documented by many pictures and accounts by missionaries. The system resulted in many victims losing their right hand, without necessarily being killed first. Many others lost upper or lower limbs by being chained too tightly and contracting gangrene. No official demographical data existed prior to 1908, but the combination of an inhumane labour system, starvation, killings and epidemics is estimated to have resulted in the halving of the population between 1880 and 1920, a total 10 million deaths.

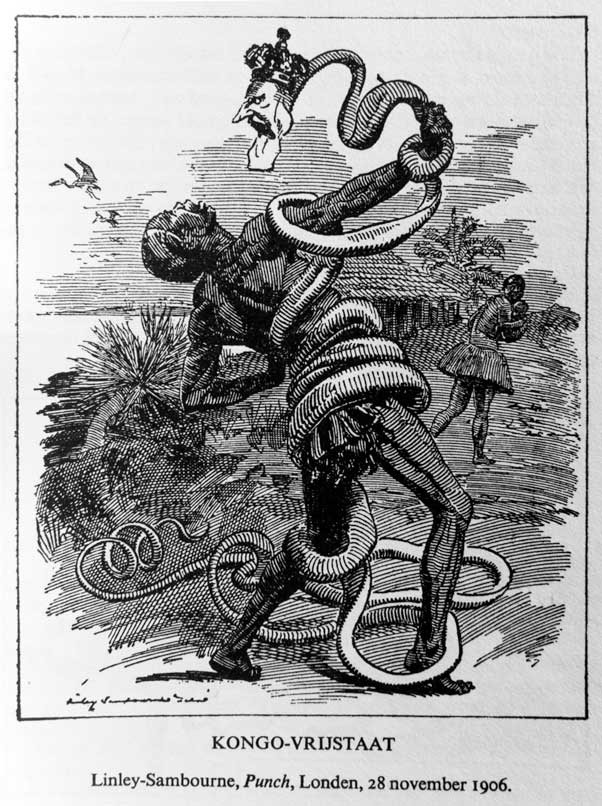

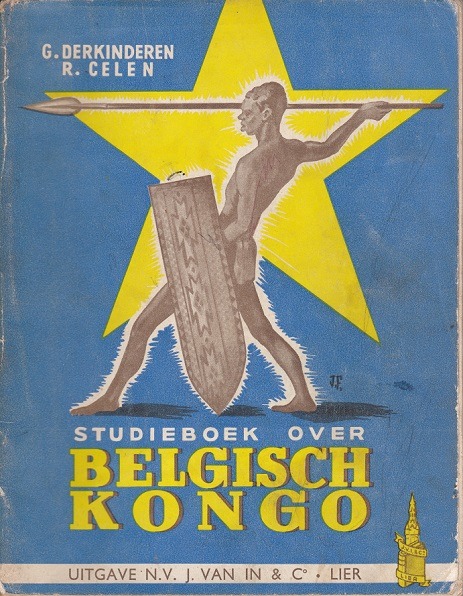

Well known caricature (1906) of Leopold II. Belgian Congo studybook (1953) for use in the Colonial School.

Leopold’s façade of a “humanitarian, civilizing project” was a fraud to blind the public in Belgium and the international community. Old slavery was replaced by mass exploitation. Any humanitarian efforts were only observed by the handful of missionaries in the country – not by the omnipresent concession companies or the government agencies.

A colony unprepared for independence

Already in the late 1880’s, outcries from Africa reached the rest of the world, thanks to the missionaries that were sent to the Congo to convert the inhabitants. Following some pamphlets, detailing the horrors, the Congo Reform Association was founded in 1904 by R. Casement and E. D. Morel. The King responded with counterpropaganda. However, when the King assembled a commission, it confirmed, to his own surprise, the accusations. This would lead to the annexation of the Congo Free State as Belgian Congo in 1908, now a full colony of Belgium.

In June 1960, Belgian Congo became independent as the Republic of the Congo, after an uprising in the previous year and following a wave of decolonization throughout the African continent. A month earlier, the first national elections ever in Congo were held. Patrice Lumumba’s Mouvement National Congolais was victorious. However, his rival Joseph Kasavubu became president, since he was more acceptable to the Belgians. Lumumba was to be prime minister. But unrest started when provinces Katanga and Kasai rebelled, backed by Belgium and helped by their military presence. Lumumba was accused of having asked the Soviet Union for support and of being a Communist. Kasavubu dismissed him as prime minister.

The Belgian Minister of African Affairs had communicated it was necessary to “eliminate” Lumumba and CIA missions were planned. After a putsch by Colonel Mobutu, who later ruled Congo as a military dictator until 1997, Lumumba was arrested in December 1960 with the tacit support of the United Nations. In January, Lumumba was moved to a prison in the rebellious province of Katanga, allegedly because it was feared that his supporters would free him. In Katanga, he would lack support. Lumumba was immediately executed upon his arrival at the prison in this province, which was actually still completely under Belgian control. Belgian officials disposed the body. Nobody was ever tried before a Belgian court.

In 2002, the Belgian government admitted to having had “undeniable responsibility in the events that led to Lumumba’s death”. However, the government did not take full responsibility but issued a public pardon. In 2011, Lumumba’s three sons sued a dozen Belgians for their possible role in the murder. A court in Brussels accepted the case and investigations are still ongoing.

The country was known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (1964-1971), the Republic of Zaire (1971-1997) and again as the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1997 on – each with their own tumultuous episodes. Their flags bear the golden star in a blue field, still referring to Leopold’s AIA as if their history is forever intertwined. Belgium continues to closely watch the country and is now criticizing its dysfunctional democracy and electoral processes – more so than any other country or international body - as if to repent for its sins during King Leopold’s reign.

The history of Congo is still being written, literally. One of the most influential efforts to write a fuller story came with David Van Reybrouck’s book Congo: The Epic History of A People (2009). It is written with a literary-journalistic approach, even reconstructing historical conversations. The book relies heavily on contemporary oral history and personal travels to bridge historical narratives. It is one of the first efforts of someone trying to write Congo’s history from a non-Eurocentric viewpoint.

Congo and the museum in Tervuren

The circle is now complete. We end where we started the story, at the grounds of the same museum in Tervuren. The contrast between what is happening today and what took place in Congo and at the Colonial Exhibition in Brussels in 1897, in almost bucolic scenes, could not be more extreme. The exposition at the Palais des Colonies was so popular that it became permanent as the Congo Museum in 1898.

It was not only a permanent museum, but also a research institute. The Palais soon became too small, since the collections were steadily growing. The commencement of the new building started in 1904 and was finished in 1909. It was opened officially the next year. The result was a massive and impressive palace, with its halls and contents having a majestic beauty.

In 1960, soon after the independence of Congo, the museum became the Royal Museum of Middle Africa. The focus shifted on ethnography and anthropology. In addition, the geographical scope became broader, going beyond the borders of the former colony.

Part of the indigenous collection in the Palais de Colonies

The museum was for a long time “a museum on itself”, showing how the collections actually were presented. But the tragedies that took place in the Congo Free State were never fully documented at the museum. These stories seemed to be lost in time and silenced. The book by Hochschild sparked a new international outcry. This was partially addressed by the museum with a temporary exhibition called “The Memory of Congo” in 2005. This still did not go far enough for some.

Royal Museum of Central Africa before the extensive renovation and expansion

The museum is currently closed. In fact, it has been inaccessible to the public since 2013 and is undergoing a massive renovation and expansion. The total cost: close to 75 million euro. It will no longer just be a colonial museum, but a “place of life and memory” and “brought into the 21st century”. Its director, Guido Gryseels, says that Belgium “cannot ignore the extreme violence that marked the beginning of the colonization and the measures of apartheid that were instated in Belgian Congo”.

You will soon enter the museum through an impressive new glass pavilion. An underground hallway will increase the space of the permanent collection, while respecting the original concepts of the other halls and showing their painstakingly restored murals. A new hall will now tell the history of pre-colonial Africa, long ignored in the previous concept.

The revamped museum faces a challenging task in bringing the story of Congo to a broad public. What happened in Congo and Belgium’s relation to it then and now is no longer a secret history. The museum should disclose the brutal domainal system. The victims, who could not cry out for help, deserve this. A memorial room is also long over-due. It should show Leopold’s greedy scheming and compare it to how other colonial powers treated their subjects.

The grounds of the 1897 Exhibition at Tervuren, today

It should also show how the Colonial Charter from 1908, though an improvement compared to Leopold’s “free state”, did not provide for a free press and continued to allow forced labour up until 1960. Education for the blacks was kept very basic and focused mostly on technical skills, “out of respect” for their cultures and traditions.

The system was elitist and served the white colonialists. The blacks were still treated paternalistically. Most, if any, positive accomplishments in education and rights were only achieved a few years before Congo’s (rather unforeseen) independence. But these came too late. Congo was not prepared for independence and was plunged into a civil war with Belgian involvement.

We know that the museum is heading in the right direction, with a new hallway for its permanent exhibition. But we do not know how far it will go. In fact, all the details are still being worked out.

We’ll have to discover it for ourselves, when the museum reopens in June 2018.

By Tom Vanderstappen