The modern circus is viscerally enthralling. It might no longer have elephants, tigers or lions but it has artists who perform death-defying physical feats.

They include aerial acrobats suspended in the air, spinning precariously on tightropes, on unicycles, or held by their partner’s hand grip. There are artists who engage in extreme contortion, bending and twisting their bodies into seemingly impossible shapes. And there are extreme jugglers who perform rapid complex routines, synchronising with other performers to create a magical hypnotic effect.

While the traditional circus is a spectacle of unrelated acts mostly performed under a travelling big top by a family whose craft is passed down through generations, the contemporary circus is more open in style and skill. Sometimes known as the new circus, its origins emerged in the 1970s in street theatre, with artists trained in circus schools or from sports or dance backgrounds.

The new circus keeps many traditional circus disciplines – acrobatics and manipulation of objects for instance – but gives them a more theatrical nature and highlights the artist’s contact with the audience. The show usually has a throughline, addressing spectators with a certain topic or problem, rather than just displaying unusual abilities.

Belgium is packed with circus and street theatre. There are 50 circus arts schools – some for children and some for adults seeking to make it their profession – and well over 150 circuses in the country.

Tightrope walkers and acrobats performing at the Hopla! festival.

The result is not only great street theatre but also free events featuring outstanding talent – like the Hopla! circus festival which takes over various Brussels neighbourhoods for a week in April, Festival Up! and Festival Zonder Handen. Even the quality of the busking is monitored in Brussels: to get a permit, the prospective artist must have the appropriate artistic diploma or, if not, can appear in front of a monthly jury at city hall and audition.

Among the schools, the heavyweight is Ecole Supérieure des Arts du Cirque (ESAC) in Brussels, considered one of the top three schools in the world. Other major players include the Ecole du Cirque de Bruxelles located in one of the hangars at Tour et Taxis and with a second campus in Saint-Gilles.

In Ghent, the Circuscentrum supports and promotes the over 20 schools and 90 circuses in Flanders, while La Maison d'Alijn, a museum in Ghent, houses a prime collection of circus memorabilia. In Wallonia, support is provided by Fédécirque. And Franco Dragone, the Belgian director and developer of the Cirque du Soleil, still has his headquarters in La Louvière.

The many schools are testimony to how today’s circus artist is not limited to one discipline and is often a clown, acrobat, magician, trapeze artist, storyteller, athlete, musician, singer, dancer and more.

Juan Manuel Cersosimo and Ricardo Delpine, of Che Cirque & Theater based in Brussels, illustrate this. "Ricardo is crazy for music and I'm crazy for bicycles so we put our two passions together," says Cersosimo, describing their genre-defying act in which he plays music on handmade instruments while Delpine does perilous stunts on his bicycles.

"We are tamers: I am taming bicycles and he is using bicycles to make musical instruments. We have a bass, cello, guitar, harp and percussion handmade with parts of bicycles. We replace tigers and lions with wheels and bikes."

The International Street Arts Festival in Chassepierre, Florenville, Saturday 19 August 2023. Credit: Belga / Nicolas Poes

The Belgian travelling circus has a rich history that spans centuries. Its origins can be found in the street theatre and fairs of the Middle Ages during which talented artists wowed the crowd with acrobatics, juggling and animal taming.

The first modern circus was created in London in 1768 by Philip Astley who went on to establish 18 other circuses in cities across Europe. In Belgium circus shows evolved to include colourful marquees, decorated caravans and a variety of impressive acts, creating a circus tradition well-rooted in local culture. The fusion of music, elaborate costumes and spectacular sets added a theatrical dimension to the travelling circus, captivating an ever-growing audience.

The Brussels bond with circus arts even led to the raising of a statue of a clown, Heroic Pierrot, in 1924, on Square de l'Aviation, opposite the traditional Midi/Zuid fair (it was commissioned to commemorate fairground workers killed in the First World War).

Fertile ground

Why is Belgium such fertile ground for the circus arts? “Belgian culture is very visual, probably in part due to the linguistic situation that means that movement, dance, visual arts have become a huge part of the culture,” says Kevin Brooking, who came to teach clowning in Brussels 35 years ago from Kansas City in the US and never left.

Brooking says Belgium’s proficiency training helps raise the performance culture. “When I started clowning 50 years ago, juggling five balls was considered amazing and five clubs as out of the question, but now ten-year-olds are juggling five clubs,” he says.

Another factor is money: Belgium funds circuses, circus schools and initiatives like the Belgian chapter of Clowns without Borders, which Brooking co-founded. Clowns without Borders performs in refugee centres and runs workshops for refugee children. “This brings up all the joy and creates a huge energy and positive light in an otherwise grave atmosphere,” he says. It also has a project in regular Belgian schools called Listen to Me When You Talk that helps children with conflict resolution and non-violent communication.

Street festivals

When it comes to events, Belgium is home to one of the world’s largest, oldest and most-respected street theatre festivals: the Festival International des Arts de la rue de Chassepierre, held every August. The village of Chassepierre in the Ardennes is closed to traffic for two days and becomes a giant outdoor theatre as the street and circus performers from around the world enthusiastically show up and give it their all.

Lessines, René Magritte’s hometown, also organises a very Belgian annual festival known as the Rallye de la Petite Reine (la petite reine, or little queen, was the French term for a bicycle at the turn of the 20th century, supposedly because Queen Wilhelmina ascended the throne of the Netherlands at the age of ten and popularized the use of the bicycle).

To take part, festivalgoers ride a bicycle through the Lessines countryside stopping at ten locations including châteaux, quarries, riversides and even the historical, UNESCO-listed Hôpital de Notre-Dame de la Rose, where they are treated to circus acts put on by top international and Belgian troupes. If 25 km by bike is too much for you there is a little train.

Related News

- Art and events in and around Brussels

- Belgian and French fairground culture listed as UNESCO Intangible Heritage

- 'A generational craft': The stallholders running the show at this year's Foire du Midi

Latitude 50, created in 2007, is officially the centre of circus and street arts for the Wallonia Brussels Federation for its activities oriented towards the public and towards professionals. Based in rural Marchin, Latitude 50 hosts a dozen performances annually, co-organises street art festival Les Unes Fois d’un Soir in Huy and provides residency space to some 60 companies every year to develop their new creations. About 150 artists come by every season to create their own show.

One of the many roaming shows, Circus Ronaldo stands out for its blend of theatre and circus. It started in 1842 when Adolf Peter Van den Berghe ran away from his home in Ghent at the age of 15 to join the circus. He went from stable boy to acclaimed equestrian acrobat and after crossing paths with a travelling theatre group and marrying one of the performers, he and his wife formed their own company, which was eventually named Ronaldo.

Performed by generations of the same family, over the past 25 years they have toured the world, but still fit in performances in small Flemish villages and towns, and were recently named as a Flanders Cultural Ambassador.

Traditional big top

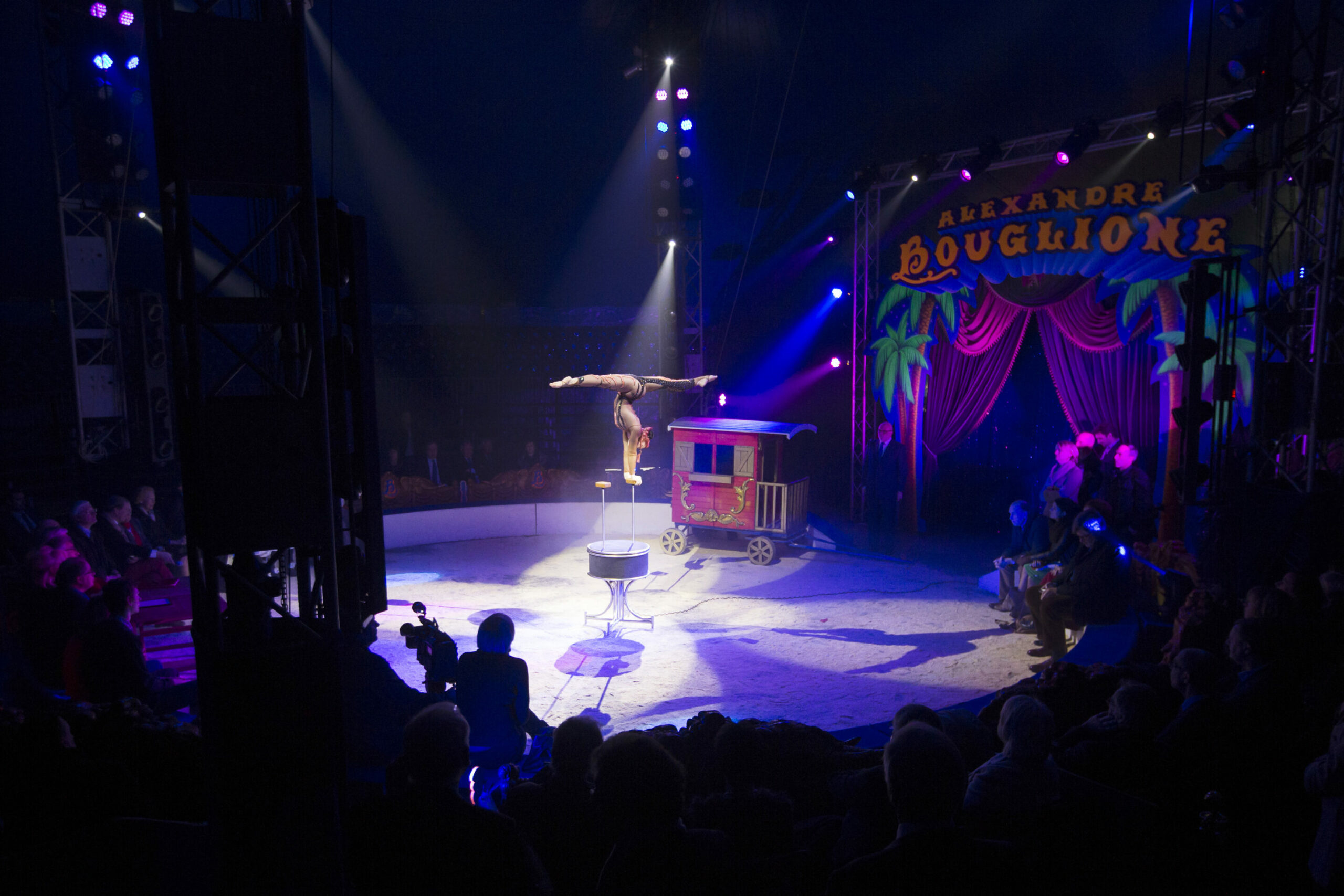

For the classic experience under a big top, orchestrated by a ringmaster, and perfumed by fresh popcorn, Belgium boasts Cirque Alexandre Bouglione, a bastion of the traditional circus.

This year is the 125th anniversary of the Bouglione family’s arrival in Brussels and their big top is mounted by the Atomium for November after which they set up on Place Flagey for December, offering completely different shows in the two locations.

Alexandre Bouglione circus on Place Flagey in the 1970s.

Alexander Bouglione, seventh generation, started as a bear trainer. “In the beginning, they were bear trainers. They came from Italy and crossed the Alps with bears. And then they had fairground menageries. And then it was the circus,”he says.

Bouglione limits himself to just October to December. For the spring and summer his son Nicolas tours Belgium with Cirque Nicolas Bouglione and his daughter Anouchka tours in North America with her circus Cirque de Paris by Anouchka Bouglione.

Bouglione prefers the traditional circus, but he does have contemporary acts in the current show, and he has some performers who are not members of a performing family. About a quarter of his performers come from schools, and the rest are from generations of circus families.

“I have the Garcia family. They've also been doing the circus for 200 years. They're mixed, they're half Irish, half Spanish so they also perform as the Fawcett Circus in Ireland and England.”

Alexandre Bouglione circus in December 2014. Credit: Belga / Kristof Van Accom

While his time on the road is now only three months in the year, he has stuck with life in an archetypal travelling circus caravan. “I live in my caravan,” he says.

“I'm going to be 69 in a few days. I don't want to build a house at 69. The caravan is good. We were born in caravans. We're gypsies. This is our custom.”