Somewhere in the newly-urbanised Coronmeuse, in the shadow of the Monsin dam on the southern end of the Albert Canal where the Meuse curves, Watermael-born civil engineer Alexandre Delmer likely stood in soft ground – the kind of loam-laden earth so consistently subject to digging and displacement that it settles only slightly, inhibited by suspicion.

The year was 1933 and the area was a flurry with an important construction project that was known, even then, to be of historical significance. Again.

The Exposition Internationale de 1930 de Liège, commemorating a century of Belgian independence, had only recently transformed the landscape with promenades, pavilions and modernist façades. Before that, the Pont de Coronmeuse had been built to welcome these international guests. And in the same decade, an international exhibition of water technology would take place – thanks, in part, due to what Delmer was watching unfold now: the true birth of the Albert Canal.

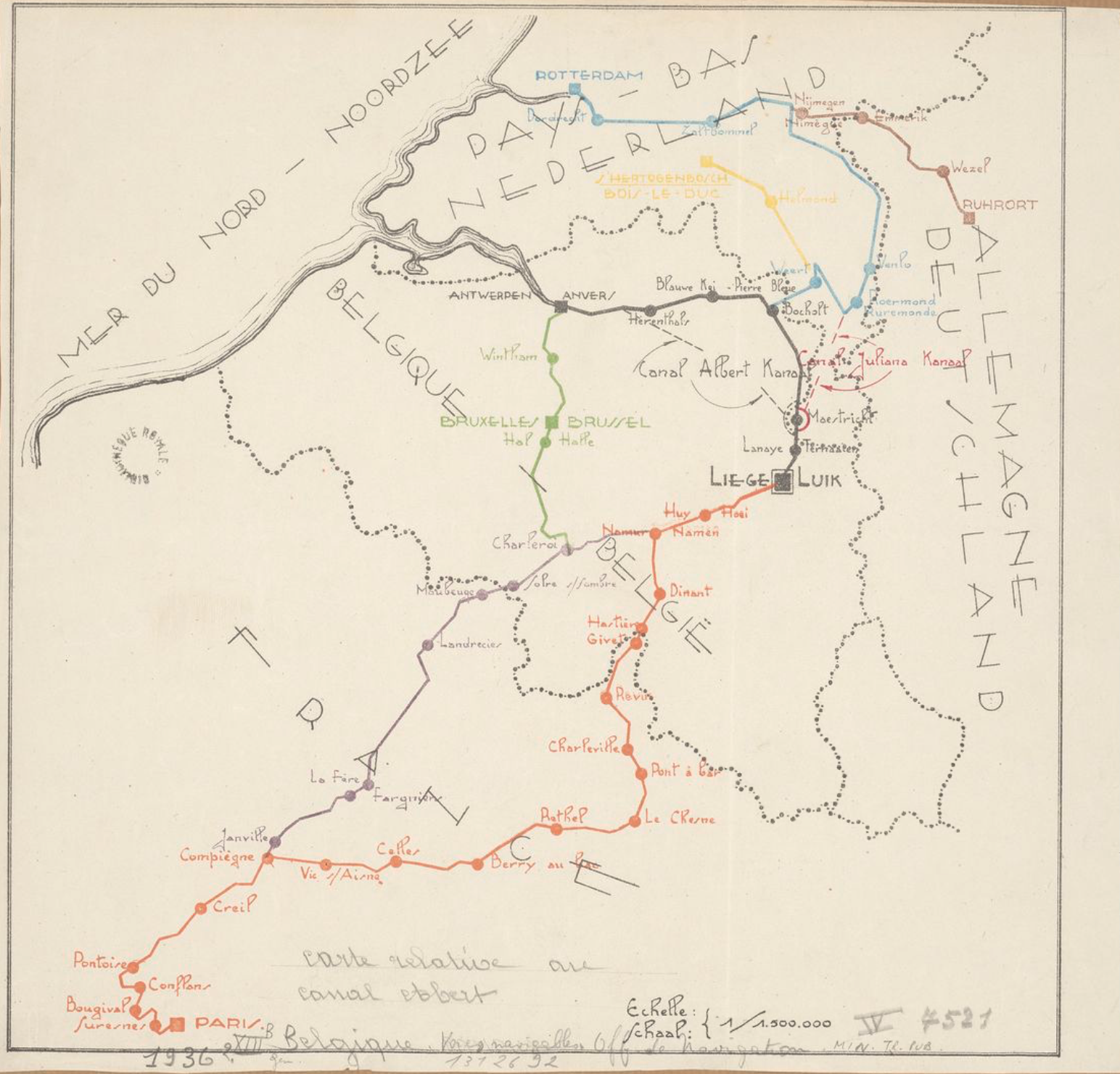

Stretching 129km from Liège to the Port of Antwerp, the Albert Canal is a wide, engineered artery that threads through four major river basins – Meuse, Demer, Nete and the Lower Scheldt.

Under normal conditions, the Meuse delivers an average flow of some 250,000 litres every second. But that figure can swing dramatically, peaking as high as 3,260 cubic metres – roughly the volume of an Olympic swimming pool, every second – or falling to just 35 cubic metres per second, dangerously close to the minimum 30 cubic metres per second required to function normally. In such moments, when rainfall recedes and the river slackens, the strain on Belgium and the Netherlands becomes immediate and deeply felt.

What Delmer saw rising from the mud wasn’t just infrastructure – it was a system of balance.

Alexandre Delmer

"The construction of the Albert Canal, begun in 1930, has entered a decisive phase since la tranchée d’Eygenbilsen was first put to tender,” he wrote. “The time has come to give some explanation for this important work."

Delmer would have been besieged by noise at any visit to one of the canal’s many worksites – noise and mosquitoes. The construction took just under a decade, astounding for the time and made possible only through the relentless labour of 13,000 people, using mostly shovels and occasionally crude machinery. It was backbreaking work, but in the wake of the economic crisis of the 1930s, the state-sponsored jobs were critical and coveted.

While his paper, Le Canal Albert: les raisons justifiant sa construction, les conditions de réalisation, l'état d'avancement des travaux, was exhaustive in both title and in its promised explanations for building the canal, its conclusion can be found in two short sentences: “These canals have provided and continue to provide a great service to commerce. They have, unfortunately, become insufficient.”

Built for coal and change

Delmer’s words appeared in the Bulletin of the Belgian Society of Engineers and Industrialists, and when penned by the then Secretary-General for the Ministry of Public Works, they carried weight.

Delmer completed his secondary studies in Greek and Latin at Collège Saint-Servais in Liège before graduating from the University of Liège in 1903 as a civil mining engineer. He worked in Liège’s coal mines and in those of nearby Seraing, rose to the position of Director-General of Mines and held the same title at the Ministry of Economic Affairs, served in the Belgian army during World War I and, just for good measure, contributed to the preparation of the Treaty of Versailles to round out his illustrious biography.

In other words, he knew what he was talking about. And what Delmer was talking about, so obvious at the time that it could be assumed without stating explicitly, was the black heart of Belgium’s industrial engine: coal.

This aerial drone image shows boats lined up before a closed lock in the Canal Albert canal in Wijnegem, during a strike action of the personnel manning the locks in Flanders. Credit: Belga / Eric Lalmand

The Albert Canal was built for three primary reasons, as Liliane Stinissen of the Vlaamse Waterweg that manages it on the Flemish side (Société Publique Wallonie serves the Walloon side) succinctly summarises: first, the existing water route between Liège and Antwerp had become overly congested; second, the journey was excessively long (12 days compared to the current average of approximately 14 hours); and third, though less frequently discussed, to serve a strategic military purpose.

This last point became moot when Fort Eben-Emael, integral to the canal’s defence, was swiftly neutralised by German forces during the Second World War, which perhaps explains why it isn’t trotted out much anymore. There was also the not-so-minor threat of Dutch competition in the form of the Juliana Canal (opened in 1934) which could have diverted traffic away from Liège. But the most critical reasons, of course, were related to shipping, and what the canal mostly shipped then was coal.

Change over time

The canal has undergone several transformations over the decades, evolving in step with the demands of both waterborne transport and the planet’s climate. Its first major renovation came in the 1960s, not long after its original construction, as far as monumental infrastructure goes. But ships were changing fast: they were getting larger, heavier, quicker. The canal had to keep up.

In 1968, authorities launched a sweeping renovation campaign: the canal was widened to 100 metres, its embankments fortified, and each of the six main lock complexes was equipped with a larger lock, 200 metres long and 24 metres wide, to accommodate the rise of push towing.

Albert Canal

Traffic didn’t merely increase – it transformed. As container transport surged and cargo vessels grew taller, the canal faced new constraints: too many bridges too low to allow four-layer container stacks, and a stretch between Antwerp and Wijnegem too narrow to absorb the pressure.

Beginning in the early 2000s, a second wave of modernisation tackled these bottlenecks head-on. Between 2007 and 2024, some 50 bridges were elevated to a uniform clearance height of 9.10 metres, unlocking the canal’s full logistical potential. Its physical form had been retooled; its purpose would soon follow.

One imagines Delmer, doffing his cap and reviewing the work with cautious pride. The engineer who once fretted over pinch points, Dutch competition and wartime vulnerabilities might not have foreseen containerisation or climate adaptation, but he would have recognised the logic and admired the ambition: address inefficiencies; dispel the limitations of geography; anticiper l'avenir.

While the canal’s original lifeblood was coal, which it ferried from the region to factories and furnaces as far off as Sweden, it wasn’t long before others saw the potential of its reach. Steel, grain, cement, chemicals – more and more of Belgium’s shipping shifted onto water. The Albert Canal became not just a coal route, but the jugular vein in the capillary system of Belgian logistics.

And, of course, the face of industrialisation too has shifted. Where once the canal served a fossil-fuel-focused economy, today it plays a central role in the country’s efforts to build a sustainable future – the kind resilient enough to face the pressures of a changing climate.

Still water runs clean

Everything the Albert Canal ships on a barge is one less thing to send by truck.

“Roughly 40 million tonnes of goods are transported on the Albert Canal each year,” Stinissen says. “That’s equivalent to about two million trucks taken off the road; and it’s not just coal anymore, it’s containers, and those carry everything.”

For the companies that line its banks, the Albert Canal is more than just a waterway – it’s a low-emission lifeline. Take Gosselin Group, for one example: a company born in Antwerp around the time of the canal’s construction, now grown into an international logistics powerhouse.

Gosselin ships over 40,000 containers a year in special transport alone – about 10 percent of its total haul. These are massive loads: freight that, if moved by road, requires multi-vehicle escorts, polluting convoys, and a lot of highway real estate (one wonders what Delmer would have made of oversized turbine blades slipping past his old bottlenecks).

This aerial drone image shows boats lined up before a closed lock in the Canal Albert canal in Wijnegem, during a strike action of the personnel manning the locks in Flanders. Credit: Belga / Eric Lalmand

“If it fits in a container, we ship it,” says Marc Eennaes, Gosselin Group’s Operations Director. “With flat racks and open containers, that includes things too wide or too high for a regular lorry. It’s 40,000 containers off the road, just from one company - that’s 181 trucks a day we’re keeping off the highways. The Albert Canal lets us do that.”

Transporting goods by barge emits far less greenhouse gas than moving them by truck, and fewer lorries mean less noise, less particulate matter, and fewer hours lost in traffic jams. This is especially critical in Belgium, where roads like the R1 (the Antwerp Ring) are not only notoriously congested but also bordered by neighbourhoods suffering from chronic air pollution. The World Health Organisation has repeatedly flagged the health effects of living near high-traffic motorways, especially on the heart and lungs.

“It’s better for the environment, it’s efficient, and it’s an easy way for us to get our containers to the Port of Antwerp-Bruges. Everything moves through the port. That’s why the canal is one of the most important veins in Flanders, in Belgium,” Eennaes says.

But he is quick to add a reality check. “To be clear: there will always be trucks. If you need something quickly, it’ll go on a lorry. But if we can take these special transport loads off the roads, that’s huge.”

Fewer trucks also means more room to breathe – literally and figuratively. The industrial space around the canal is increasingly being shared. The Albert Canal has become a popular cycling route, winding past factories and freight terminals with surprising charm. The people who once used it to haul raw materials (from coal to concrete) now share it with those moving everything from kitchenware to cardigans to cartons of juice.

Illustration shows aerial view of the Albert Canal and the cement factory CBR in Lixhe (Vise) at the boarder with the Netherlands, Wednesday 16 September 2020. Credit: Belga / Eric Lalmand

Yet the canal isn’t just for shipping – or even just for people. It plays a quiet role in keeping much of Flanders alive and watered. Nearly half the region’s drinking water is sourced from the Albert Canal. Farmers fill tanks from stations along its banks to irrigate the fields that feed the country. And in drier months, that same water is redirected into nearby nature preserves, helping ecosystems endure heat waves, farmers maintain crops, and urban areas stay hydrated through even the driest months.

In the record-breaking summer of 2020, when rainfall dwindled and temperatures spiked, the canal showed both its value and its vulnerability: water levels dropped so low that vessels waited up to four hours at locks, forced to queue until each chamber was full enough to justify operation. Freight and pleasure boats were grouped together, efficiency overtaking convenience, helped along by mobile pumps at Wijnegem brought in to return water upstream – a quiet choreography of crisis management that, remarkably, kept the canal operational when other routes imposed restrictions.

And in the fatal floods of 2021, the canal became part of the nation’s reckoning with water itself – too much, too fast and too close to home.

A century on, still vital

For nearly 100 years, the Albert Canal has never stopped doing the heavy lifting. But these days, the weight it carries includes a growing sense of ecological responsibility.

While companies like the Gosselin Group are helping expand critical stretches and strengthening connections to neighbouring countries, the canal’s most common end destination remains unchanged: the Port of Antwerp-Bruges. This inland connection to the sea remains Belgium’s most important freight waterway, now more than ever.

The Albert Canal handles some 40 million tonnes of cargo each year – or about half of all waterborne freight traffic in Flanders – making it Belgium’s busiest canal. Along its length are five major inland container terminals – Genk, Beringen, Meerhout, Grobbendonk, Deurne – specifically designed to streamline shipping logistics for businesses big and small. Together, these terminals process over one million twenty-foot equivalent units annually.

It remains an engineering marvel. Its largest lock uses, each time a ship goes through, up to 50 million litres of water – as much as around 20 Olympic swimming pools. Thanks to a massive and recent infrastructure project raising 50 crossings, the canal allows ships stacked four containers high to pass freely beneath every bridge. With all bridges now raised to 9.10 metres, the canal supports not only four-layer container transport, but also short-sea shipping, high-cube containers, and oversized project cargo. This means fewer chokepoints, fewer delays and a much more attractive alternative to road freight.

Quayside at Visé

“For us, the Albert Canal is quite an important corridor – about 13.4 percent of all our traffic comes and goes through the Albert Canal,” explains Port of Antwerp-Bruges Joyce Caluwaerts. These numbers put the canal in the top five most critical corridors for the Port of Antwerp-Bruges. The regional agencies that manage the canal, the companies that thrive on it and the port that often serves as its final stop don’t just work together on shipping matters, but together towards a unified vision that centres around environmental impact.

Perhaps the biggest of such collaborations taking place is the Oosterweel works – a massive undertaking aimed at completing the Antwerp Ring, (it is not a yet true ring but a half-circle). Its summation entails the lofty goal of “a greener city”, a Ring that “no longer cuts city districts in two but connects neighbourhoods with one another.” The works, Antwerp promises, “not only make the city breathe again, but the whole of Flanders.”

This isn’t just logistics – this is long-term strategy. The Flemish government, through the Vlaamse Waterweg, is investing €263 million per year into future-proofing the canal network. New hydropower-pumping stations now allow lock water to be recirculated upstream – minimising loss during drought, and even generating electricity when flow allows. As dry seasons become the norm, these systems sustain more than just navigation. They keep water flowing to industry, farmland, homes. They manage scarcity with precision.

Every container shipped this way supports more than just trade, each actor affirms. It supports a country trying to move smarter: cleaner freight, fewer trucks, fewer emissions and a continued shift toward waterborne transit as a pillar of sustainable development.

Flow of water and time

Somewhere in Liège in the mid-1930s, Delmer likely scraped the mud off his boots and shrugged off his overcoat before sitting down before his typewriter, determined to ignore the itch of mosquito bites and properly communicate the importance of what he was watching take place. He had much praise for the history of the region’s waterways and the progress made so far – progress that, as he wrote, had "opened to Meuse navigation a route to the sea."

Canal Albert

“Traffic reaches five to six million tonnes per year on certain sections of the canal,” he wrote – a whisper of a fraction of what the canal carries today. “Its steady increase – keeping pace even during times of crisis – along with improvements to operations, gives the impression that there exists, in potential, an enormous volume of traffic, far greater than what is currently transported, which would benefit from a new, large-scale, high-capacity waterway.”

He was right about his tranchée d’Eygenbilsen.

A body must circulate, or it collapses. A country must adapt, or it crumbles. The Albert Canal is how Belgium remembers both truths, and reminds itself that permanence is found in neither coal nor cement, but from the decision – again and again – to move forward.