It is a source of wonder that the two soaring geniuses who created Early Modern English both came from small towns near the Welsh border, both were called William, and both wrote with such effortless beauty that they forged English into a tongue to compete with French, Italian, German, and Spanish.

But there the similarity ends. Shakespeare was a rock-star: favoured by Queen Elizabeth, lauded by his peers, unpolitical, and, it is said, something of a roisterer. He spoke "little Latin and less Greek."

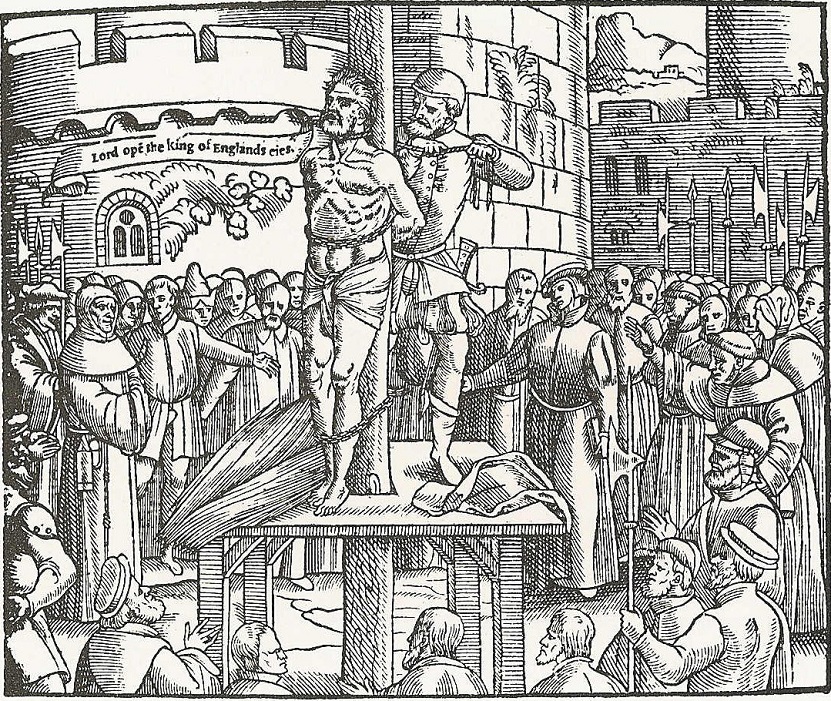

Tyndale, on the other hand, was a man of God and spent his life industriously translating the Old Testament from Hebrew and the New from Greek. He spoke and wrote eight languages fluently. He was often on the run from Henry VIII's goons. They never got him, but someone else did. In 1536, he was strangled and burnt in Vilvoorde, then in the Duchy of Brabant, and his ashes cast into the Senne river. Whereby hangs a tale.

The indignities did not end on his death. King James commissioned a translation of the Bible in 1611 and set up a committee of England's pre-eminent churchmen to do the job.

In my enforced, church-y upbringing, as I listened to clergyman or choirboys read from the King James Bible words of breathtaking beauty, I would wonder: how did a mere committee produce anything so sublime? And the answer, of course, is they didn't. They filched Tyndale's translation wholesale, is what they did. Attribution, you will find none!

Scriptures for the masses

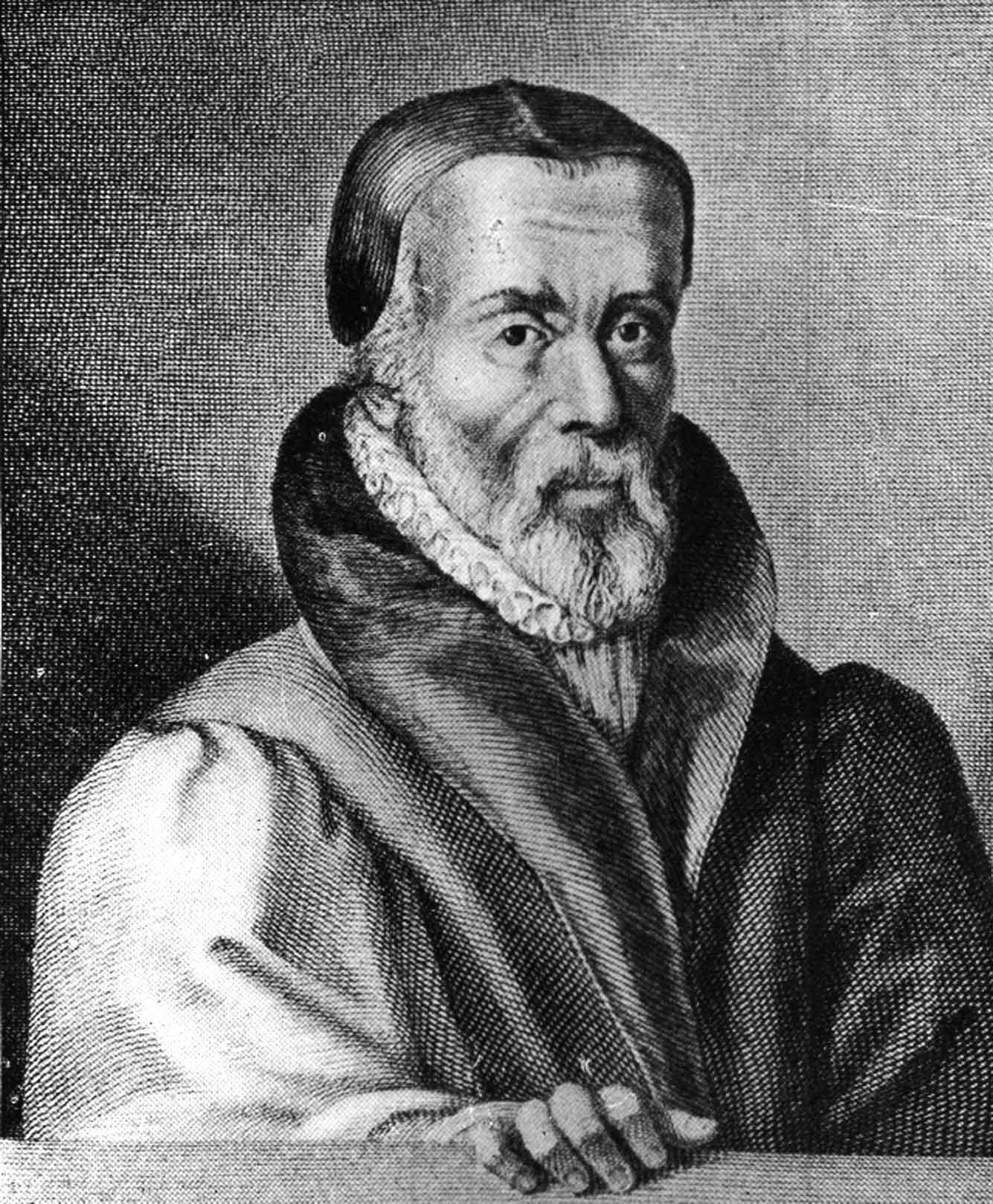

Born in 1494, Tyndale was a scholar, linguist and chaplain, educated at both Oxford and Cambridge universities. He was a driven man. He held the simple belief that all should have access to the scriptures. Therefore, the Bible should be available in English, good, clear, simple English that could be read aloud to the illiterate.

He was not the first to translate the Bible into English. John Wycliff, leader of the Lollards, headed an unauthorised effort in the late 14th century it into Middle English, but from Latin Vulgate. Tyndale, however, was the first to translate the New Testament into Modern English from the original languages of Hebrew and Greek.

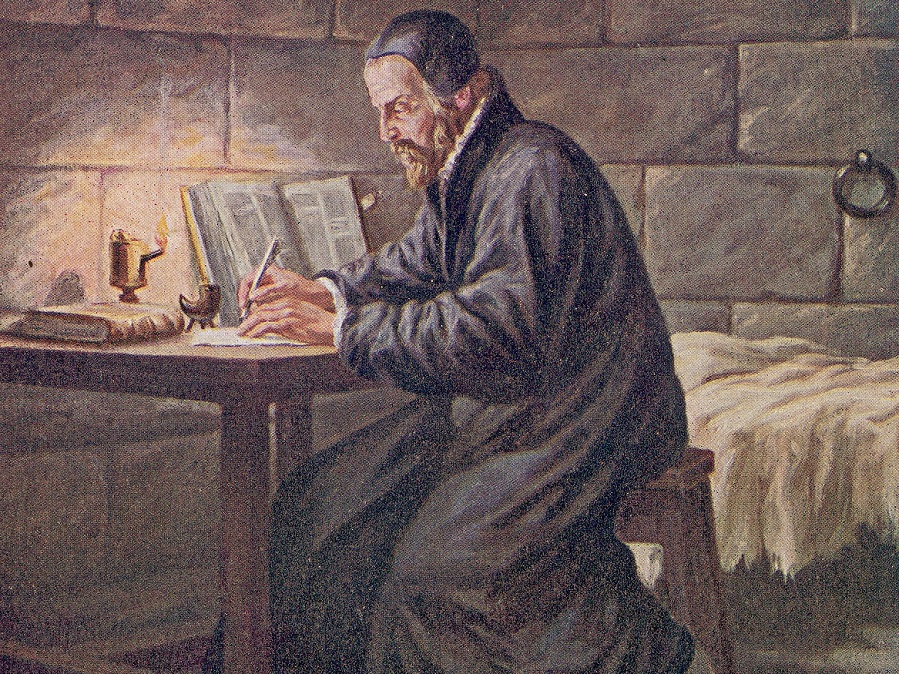

Tyndale working by candlelight

Unfortunately, this brought him into direct conflict with Henry VIII and the treacherous world of Tudor politics. God spoke Latin, the Church spoke Latin, and the power of both King and Church depended upon their mutual control of the interpretation and dissemination of the Word of God.

Tyndale made no secret of his contempt for this cosy pact. As he said to one startled cleric, "I defy the Pope and all his laws; and if God spares my life, ere many years, I will cause the boy that driveth the plough to know more of the Scriptures than thou dost." No surprise then that Tyndale had to flee to Germany and thence to Antwerp.

Stranger in a strange land

Lest he be accused of cowardice, it is worth remembering what exactly he was fleeing from. Heresy was punishable by a cruel death, preceded by torture. Chillingly, the sainted Sir Thomas More tormented his victims in the family kitchen - or rather he had others do it while he read the Bible. And he used a tree in his Chelsea garden as a whipping post; with grim irony he called it his "truth tree".

There is, to this day, a torture chamber in the Archbishop of Canterbury's London house (fallen into disuse, one trusts!). And the Tower of London was then the corporate headquarters of needless pain and death. So, Tyndale, sagely, took his leave. But he had another reason to head for the continent.

Germany, the Low Countries and northern Italy dominated printing. The printing press had arrived from China some hundred years previously. Mainz goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg had invented the hand mould and moveable type and thus large volumes of cheap books were becoming available.

The output was not small. By 1500 Europe had produced 20 million books, and in the following century 200 million. If Tyndale wanted to flood England with cheap Bibles in English – and he did – Europe was the place to be. London's printers were too few, too slow, too expensive and, above all, too visible.

For the next ten years Tyndale was on the run. History does not always record where. People trying to avoid Henry's thugs did not hand out address cards. But we know Tyndale printed his English New Testament in Cologne, escaped just ahead of discovery, and ended up in Worms for a while. He embarked upon the massive task of translating the Old Testament from Hebrew, working up to 16 hours a day. He invited criticism of his New Testament and was continually revising it.

As his Bibles poured into England, as Tyndale wrote pamphlets and books infuriating the English establishment. As his reputation as a linguist and a Christian grew, the establishment hit back. His Bibles were bought up and burnt in London by Bishop Tunstall. Tyndale commented robustly. "I shall get money from these books, to bring myself out of debt, and the whole world shall cry out against the burning of God's word.”

Growing anti-Lutherism saw him as a dangerous non-conformist. Cardinal Wolsey, the most powerful man in England after the king, condemned him as a heretic – a fatwa if ever there was one.

Henry himself asked Charles V to arrest Tyndale and return him to England. As Charles was, inter alia, Holy Roman Emperor, King of Castile and Aragon, Lord of the Netherlands, direct ruler of the Austrian heredity lands, the Burgundian Low Countries, and ruler of Spain including its Southern Possessions of Naples, Sicily and Sardinia and Spain's burgeoning American colonies…well, he may just have had other matters on his mind.

Brother’s keeper

By now Tyndale had settled in Antwerp, living with an English wool merchant and devout Protestant, Thomas Poyntz. But things began to shift in England as well. The king, frustrated at siring no heir, divorced Catherine of Aragon, married the Protestant Anne Boleyn, and turned his back on Rome. His two erstwhile henchmen and dedicated Tyndale hunters, Sir Thomas More and Cardinal Wolsey, had both met with sticky ends.

The king's affairs were now in the hands of the supremely competent, and Protestant-leaning, Thomas Cromwell. Henry, or possibly Cromwell, tried to persuade Tyndale to come home. The king's emissary met him in a field outside the gates of Antwerp and was sent back empty-handed. Tyndale spoke movingly of his poverty, his loneliness, his fears of being hunted down and cruelly put to death. But he had no trust in Henry and would continue the Lord's work where he was.

We now need to introduce a truly obnoxious character: a nasty, petty, third-rate creature. His name was Henry Phillips, an Oxford man, well-connected, but ostracised by his family. He had cheated his father out of a considerable sum of money, been chased from England, and had sent nauseatingly fawning letters to his family begging for money and forgiveness. And suddenly he was flush.

It is probable that Charles V, keen to root out English Protestants in his territories now that Henry had abandoned Rome, paid Phillips handsomely to trap Tyndale. It is bitterly ironic that this devious ne'er-do-well, trying to hustle a buck, brought down the saintly creator of the English Bible, and indeed, English itself. It is scant solace that Phillips is last seen as a low-end mercenary in one of Europe's interminable and pointless wars.

Phillips tracked down and visited Tyndale in Antwerp. Poyntz, his host, did not trust this smooth-talking Englishman, but Tyndale was hungry for gossip of Oxbridge and the West Country where they had both been brought up.

Phillips visited when the more worldly Poyntz was safely out of the way at a trade fair in Bergen-op-Zoom. The English merchants in Antwerp, or at least their residences, were subject to a kind of diplomatic protection. He therefore had to get Tyndale outside and into the street. Phillips later boasted that he offered to buy him dinner. He pushed Tyndale ahead, where he was arrested by the waiting soldiers of Charles V.

The captain said he pitied Tyndale's simplicity. Indeed! The poor man had, out of the goodness of his heart, even lent Phillips two pounds. Ten years of ducking and diving, cold and fear, working late into the night by guttering candlelight, poverty, separation from loved ones, and, of course, transcendent achievement of the highest possible order now suddenly, and shabbily, snuffed out.

Tyndale was thrown into Vilvoorde Castle, the main oubliette for political prisoners in the South Netherlands, where he was to spend the next 16 months. His cell was dank, cold, and dark. He suffered from catarrh, was interrogated frequently, and, at least for a while, was denied his books. There is a letter in his handwriting asking for warm clothes and, "I ask to be allowed to have a lamp; it is indeed wearisome sitting alone in the dark." It is a measure of the man that, despite his desperate circumstances, he did not beg or abase himself. He asked with dignity.

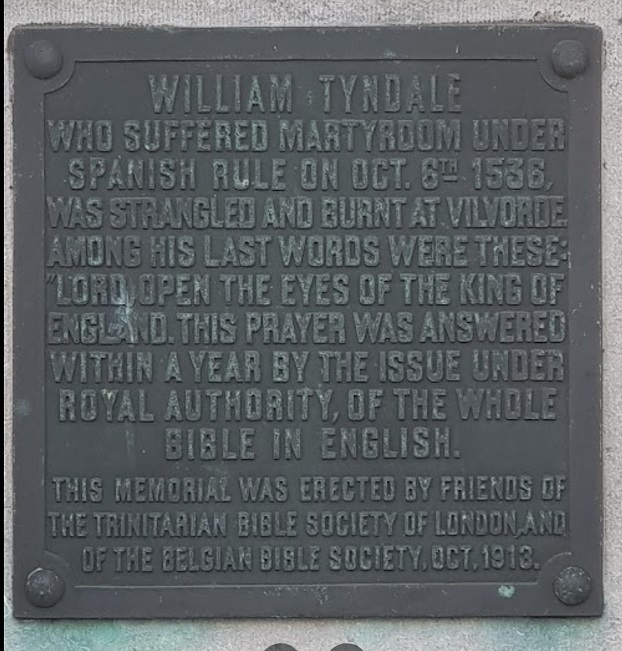

Placard on William Tyndale monument in Vilvoorde

Tyndale’s priesthood was stripped from him in a formal and public ceremony of ritual humiliation. He was then condemned to be burnt as a heretic. The Holy Roman Empire was, perhaps, more merciful than Henry VIII would have been. He was not tortured during his incarceration, and he was strangled prior to being put to the stake. His ashes were then cast in the river.

Fight the good fight

When I mentioned Tyndale to a Belgian colleague from Vilvoorde she burst out laughing and said, “Before school I used to kanoodle with my first boyfriend by his statue in the main square.” I had to inform her that the statue had now been moved to a quiet park, named in his honour, off the Mechelsesteenweg.

There is also a small and touchingly modest museum dedicated to Tyndale in Vilvoorde. When I first went there in 1995, I could get in only by going round to the Protestant Church and asking for the key.

Memorial to William Tyndale in Vilvoorde, Belgium

The pastor came to see me there, so excited was he to have a visitor. His English was poor and I knew better than to speak French. I told him I had just read a book about Tyndale and had come from Brussels to see his museum. He understood that I was writing a book about Tyndale and had come from England to see. Disabusing him was one of the hardest things I have ever done.

The castle itself is no more. It was pulled down in the 1790s. The stones were used to build a house of correction, or tuchthuis, used severally as a jail for criminals of both sexes, a military prison, a military hospital, and a workhouse. So it was that the stones that once incarcerated Tyndale continued their baleful work. The building was abandoned in the 1970s and restoration is ongoing. But you can still feel the grimness of Tyndale's imprisonment by walking around the tuchthuis on a wet day.

But, for me, the most affecting way to remember Tyndale is when you pass the Brussels city dump, or Recypark, near the Van Praet bridge, by the canal. There you may gaze severally upon the busy A12 highway, the massive municipal incinerator, Schaerbeek's railway marshalling yards, the Brussels-Willebroek Canal with its coal barges loaded to the gunwales, the dump itself, and the point where the Senne river finally emerges from the tunnel to which 19th century burghers had banished it for being too malodorous and noxious for even their strong stomachs.

In this unlovely stretch of industrial Brussels, you may feel the presence of Tyndale who bravely met his fate a couple of miles up-river. An antidote to these eyesores lies in the beauty of his peerless words: "Ask, and it shall be given"; "Verily, verily I say unto you"; "Seek, and ye shall find"; "Be of good courage"; "Fight the good fight"; and pertinently for him "Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death I will fear no evil."

His gift to us was, like Shakespeare's, beyond measure and for all time.