It’s hard to imagine that an American thriller writer who wears a T-shirt emblazoned with ‘I’m kind of a big potato’ and speaks with the accents of the Deep South will be fascinated by Jan Van Eyck’s masterpiece The Adoration of the Holy Lamb.

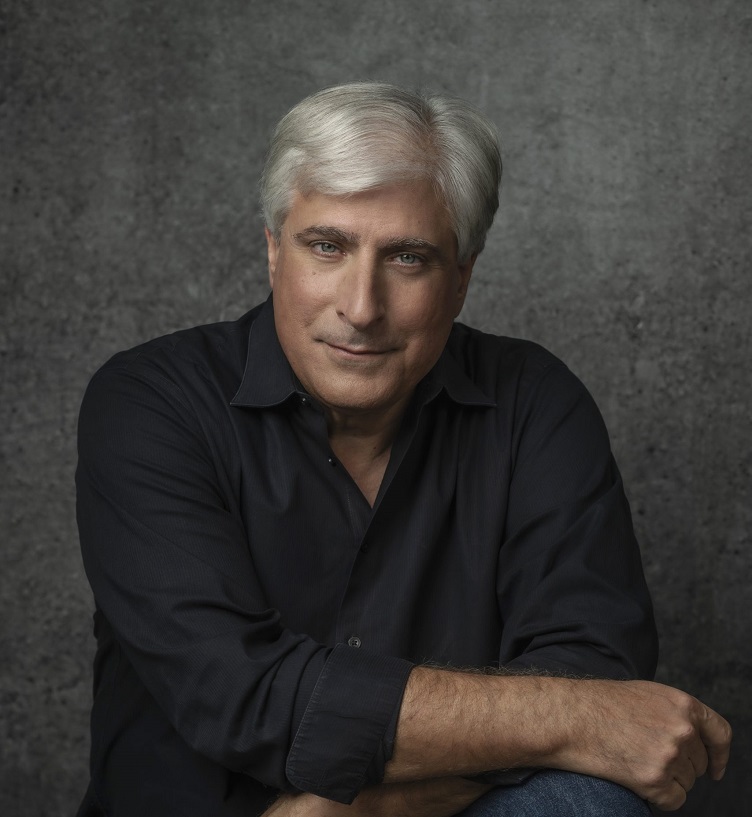

Steve Berry, who has sold over 25 million books in 40 languages in 51 countries, is a passionate amateur historian. His thrillers may be fantastical, but they are firmly based on facts. His book-a-year for the last 20 years follows an iron formula – action, history, secrets, conspiracies, and international settings.

The Omega Factor, his latest, is a frenzied wild goose chase involving ninja warrior nuns, corrupt priests, Vatican heavies and Ghent’s world-famous 15th century polyptych.

This is not the first time Berry has set a thriller in Belgium. “I like Belgium, I enjoyed the country very much, and there’s nothing to say I won’t set another thriller there,” he says. “I found the people lovely and cooperative. You couldn’t ask for better. And the countryside reminded me of rural Georgia where I grew up.”

He was in Bruges in 2017 watching the daily veneration of the holy blood at the Basilica of the Holy Blood for his book The Warsaw Protocol, when he first heard about the Ghent Altarpiece. “So we jumped into the car for Saint Bavo Cathedral, which is only a half-hour drive away. The painting was stunning, and I realised there was a novel here,” he says.

He spent a day criss-crossing Ghent on foot, talking into his voice recorder, taking hundreds of photographs, and buying up all the travel guides and books he could find in English - about a hundred that included Noah Charney’s Stealing the Mystic Lamb.

The Ghent material then sat for two years on his “ideas” shelf at home in Orlando, Florida. Speaking from there on Zoom, Berry talks knowledgeably about one of the finest masterpieces of oil painting.

Stolen panel, enduring mystery

Jan Van Eyck’s 18-panel polyptych was commissioned for Saint Bavo Cathedral and hung for decades in the chapel for which it had been designed. Seeing the way that light slants through the window, Van Eyck aligned it with his painting. For security reasons, since the 1970s the altarpiece has since been behind bullet-proof glass in a side chapel.

The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, also called the Ghent Altarpiece

The panels have had more than their fair share of adventures, from censorship to breakage, from dismemberment to outright theft. There were 12 panels originally, but in the 19th century, six were sawn to show the scenes on both sides. Painted between 1420 and 1432, it is now certain that it was started by Hubert Van Eyck and, after his death, finished by his brother Jan, who covered much of the initial work with his own creations.

The panel depicting the Righteous Judges was stolen in 1934 and has not been recovered, despite countless attempts by professionals and amateurs, detectives and even soothsayers – visitors today will see a copy of the panel in its place, made in 1939 by art forger Jef van der Veken. During the Second World War, the Nazi occupiers removed the entire altarpiece to a salt mine in Altaussee, Austria.

One theory about the whereabouts of the Righteous Judges was that van der Veken painted over the original, but X-rays have since disproved this. Berry takes that idea and runs with it in his signature world of fact-based fantasy.

His art sleuth character Nick Lee is supposedly employed by UNESCO to investigate complicated art-connected cases. Lee becomes involved with the Righteous Judges panel when holidaying in Ghent in pursuit of an old flame who has become an art restorer and nun.

No mean sleuth himself, Berry used the Closer to Van Eyck website to scrutinise details invisible to the naked eye, including the tiny flowers that are a botanical encyclopaedia of what was growing in Flanders during the 15th century. He discovered details he could use as points of departure for his fictional treasure hunt. “I always work with what’s there,” he says. “But when I take something from the past – in this case, the altarpiece – I have to make it relevant today. That’s the challenge. What does it have to do with today?”

Berry closely studied before-and-after high-definition digital photographs of Van Eyck’s masterpiece, particularly of the central panel with its depiction of the Holy Lamb. While doing so he noticed an intriguing detail on the left side of the central panel, a hamlet of gabled houses surrounded by trees. “I used those houses in the book, but when I went back later to look again, they were gone, replaced by trees and grass.”

The work had been restored since he had last looked at it and the hamlet was no longer there. Berry then asked me if I might solve that mystery for him.

Livia Depuydt, who heads studio paintings restoration at Brussels-based Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, worked for years on the panels’ restoration. She did not remember that particular detail, but it didn’t surprise her. “Restoration only became a discipline in its own right in the 1950s,” she says. “Before that painters might add their two-bits worth when fixing a painting. The latest restoration, which is ongoing, would have removed 16th century add-ons. In the case of the Mystic Lamb, it’s particularly tricky as the restorers must be certain they aren’t removing anything Jan had added to Hubert’s original.”

The same, but different

Berry is best known for his Cotton Malone thriller series of 16 books, centred on a retired Justice Department agent who runs a second-hand bookshop in Copenhagen, but is regularly drawn back into his former world. Two more of these books are in the offing for 2023 and 2024.

But he recently created a new character. Nick Lee is younger and less experienced than Cotton Malone, although the two have much in common. And Nick Lee is better suited for a thriller involving the Ghent altarpiece.

The challenge with this type of fiction, Berry explains, is that each book “has to be the same but different.” If readers like Nick Lee, he too may become a series, but with so many series now on his hands, Berry says he will need help. He is already the co-author of a Luke Daniels and Cassiopeia Vitt series, and, if Nick Lee is continued, “I’ll need help to keep him going, someone to write the first draft based on my plot.”

Steve Berry started writing at the relatively late age of 35 as an emotional safety valve from his job as a lawyer in Georgia. “When you’re a trial lawyer, you see people every day at their worst and it beats you down,” he says. “Here’s the life of a lawyer: no one ever comes to see a lawyer unless they have a problem. So, they come, ask for your opinion, don’t listen to a word you say, then blame you for everything that goes wrong. That wears on you after 30 years.”

After eight manuscripts and 85 rejections from New York publishers, along with 10 years of brutal verbal beatings in writers’ groups, he reckons he learned the craft of writing. “By book eight I had to choose between the law and writing. There was no choice. I wanted to be a writer,” he says.

So Berry turned his hobby into a full-time job that allows him to travel the world in search of stories, accompanied by his wife Elizabeth, a publisher herself who specialises in the romance genre. “She’s had three number one bestsellers in America this year,” Berry says.

The couple travels widely. Five thrillers are set in the US, the others take place across Europe, Africa, South America, Antarctica, Russia and Central Asia. “During these trips is when ideas find me. In the case of The Omega Factor, I was in Bruges, researching another novel and minding my own business, when someone mentioned the Ghent Altarpiece. You never find ideas if you go looking for them. They have to find you. Then later you find a way of putting them to good use.”