On his way to Liège, John the Fearless stopped to light a few candles at St Adrian’s Abbey church in Geraardsbergen. When he was born, his mother had offered thanks to St Adrian for answering her prayers, and now he in turn was making a stab at begging for protection. Thirty-eight years before, Margaret of Flanders had prayed for fertility; today her son was praying to avoid sudden death. How convenient that some saints could be called on for completely different things. As he rattled off his prayers, John had plenty of time to consider his situation.

The Bavarian connection was a thread that ran through his whole story. Not only did his wife come from Bavaria, but his sister had married someone from the same family back in Cambrai. And this William wasn’t just anybody. He had now become Count of Hainaut, Holland and Zeeland. In addition to a number of bastard sons, William had one legitimate daughter, little Jacqueline, who was the apple of his eye. For her fifth birthday he had arranged a marriage for her to the second youngest son of King Charles VI of France.

The half-Bavarian, half-Burgundian Jacqueline was preparing to assume control of her three principalities, and to that end she was being given a solid education: from botany through biblical history, mathematics and languages to the rules of etiquette. As a young girl she was just as good at analysing medicinal herbs as she was at knowing the correct way to wear a train. She was bright, inquisitive and not especially pretty at first glance. Yet in the coming years she would grow into the most desirable bride of Europe and would marry four times.

Her venerated father – John’s brother-in-law and comrade-in-arms William – was more of an old warhorse than a great statesman, and he struggled to hold his ground in the conflict between the Hooks and the Cods in Holland, which had been going on for decades. It was a complex hostility that was tearing his land apart, and he probably couldn’t even explain it to his daughter. He might have said that the Cods were open to change and were more interested in cooperating with cities and burghers, while the Hooks (from the hooks that catch the cod) were more conservative and adhered to the classical feudal structures.

John the Fearless from the KMSKA

But the various members switched parties so often that what it boiled down to was an ordinary power struggle, sometimes even blood feuds between families, who passed the hatchet from one generation to the next until the dispute was cancelled (or not) by means of a procedure of ‘kissing and making up’.

The fact that William had chosen the Hooks side, while his father, Albert, became more and more closely aligned with the Cods over the course of his life and finally even took a Cod mistress, showed how inextricable the Holland tangle was. This struggle for influence and power would go on for about 150 years and claim thousands of victims. One day, John the Fearless and his son Philip would also become involved, but in 1408 the Burgundian duke had other family worries.

His wife’s second brother now occupied the throne of the prince-bishopric of Liège, which comprised large areas on both sides of the Meuse and had been ruled by a prince-bishop since 985. As in Flanders, two languages were spoken there: French in the south and Dutch in the north. The Flemish counts weren’t the only ones with a turbulent 14th century behind them. The prince-bishops of Liège also fell prey to unrest.

It was John’s brother-in-law John of Bavaria who succeeded in putting an end to the chain of rebellions with his accession in 1390, but in recent years both the townspeople and the nobility had become irritated by his authoritarian style of governance. They chose Diederik of Perwez as a counter-prince-bishop, thereby winning the support of the late Louis of Orléans and of the Avignon pope Benedict XIII, the most important players in the anti-Burgundian camp.

When John of Bavaria was forced to hole up in a besieged Maastricht for a second time in a row, John the Fearless and William of Holland joined forces to keep the situation from ‘degenerating into a universal rebellion’. In short, John wanted to pull off a repeat performance of what his father had achieved in Westrozebeke, not only to enhance the prestige of Burgundy as a growing power bloc, but also to safeguard the centuries-old feudal relations: nobility and clergy at the top, the rest of humanity below. The thought of burghers rising up against their lawful lords was absolute anathema.

‘Let Them All Die’

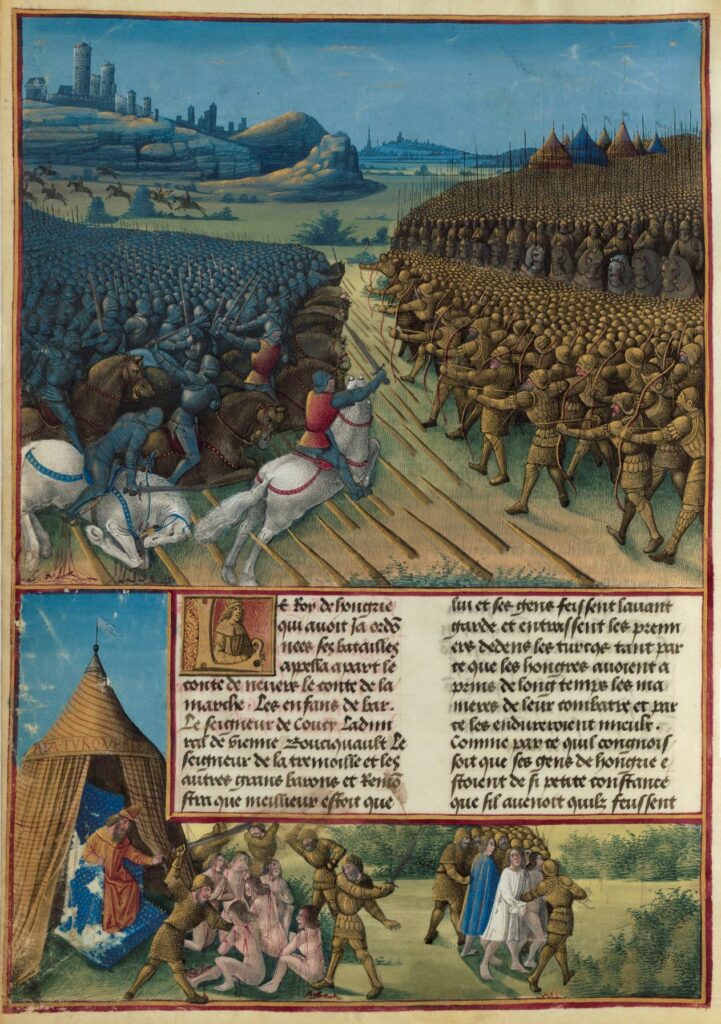

The rebels abandoned their siege of Maastricht and rushed to take on the Burgundian forces. Just outside the village of Othée, halfway between Tongeren and Liège, the troops discovered each other and decided to do battle. It was September 23, 1408, almost twelve years to the day since the battle of Nicopolis, where a combined army of Burgundians, Hungarians, Croatians, Bulgarians, French, Germans and Wallachians was routed by the Ottomans. The debacle had left an indelible scar on his soul, but now John the Fearless was forcing a rematch.

The 1396 battle of Nicopolis, where John fought with such bravery he was given the cognomen 'the Fearless'

He had learned his lesson. This time the infantry were given every opportunity to join in the fray, with Scottish archers hired with Flemish money taking up the slack. John also forbade his forces from simply attacking at random. On the contrary, he decided to wait. And he kept waiting. But the Liège rebels, who were looking down from a small hill, employed the same tactic. Not a single warrior left his hideaway. There was no noticeable movement, as if the universe were holding its breath.

Suddenly, John the Fearless’s troops found themselves under attack. Not by archers – the distance was too great for that – but by portable field artillery, an innovation that constituted a cautious advance in the waging of war. It involved a rather modest collection of culverins and ribaudequins that took quite a long time to reload. Only a few were wounded, but the troops still had no choice but to mount a frontal attack. First the duke quickly ordered 400 cavalrymen to execute an enveloping movement, which meant they would have to attack the enemy from the rear.

Seated on a small horse, John the Fearless led his troops and ordered them to annihilate the ‘insane’ and ‘vicious’ Liège rebels and to show them no quarter. He trotted down the whole front line, as if to spur each one on personally. Burgundy’s banner bore the emblem that had accompanied him for several years: a carpenter’s plane. The symbolism was unmistakable: he would shave off anything that got in his way.

John raised his voice and gave the order to attack. Hundreds of horses shot from the starting block, bearing on their backs men of steel with their shields and lances. The thunder of horses’ hoofs resounded in answer to the lightning of the artillery, a broad front of helmets and banners that were meant to prevent the Liège shooters from loading too often. Unlike what happened in Nicopolis, the assault was controlled. The captains even allowed for pauses, so the heavily steel-encased warriors and their horses could catch their breath.

When the cavalry was only 250 metres away, the Scottish archers let fly, leaving a trail of destruction throughout the Liège army. Then the horses thundered over the enemy lines. The knights knocked down everything in their path, hacking away as they went. The Liège infantry used their halberds to search out the small space between helmet and armour that was visible on every knight. Swinging with great strength, the halberdiers were sometimes able to penetrate the armour itself. If that failed, they tried to drag the riders from their horses by means of the special hook with which the halberds were fitted.

From battle to massacre

After the cavalry charge came hand-to-hand combat. It was especially frenzied around John the Fearless, who seemed to be the target of twice as many of the Liège warriors. According to chronicler Michel Pintoin he fought like a lion, parrying countless sword strokes and dealing several himself without being wounded. Despite his daring, for which he was later so highly commended, the battle didn’t really begin to turn in his favour until the 400 knights reached the Liège rearguard, where they sowed panic and confusion.

The Liège bakers, brewers, butchers, clog makers, rope makers, tanners, basket weavers, goose catchers, silversmiths, barbers and broom makers wanted to flee, but they were trapped. From one moment to the next the battle turned into a massacre.

William of Holland and John of Burgundy had agreed not to take any prisoners, despite the ransom possibilities. Even when his captains finally asked him if it wasn’t time to bring the bloodshed to a close, John answered, ‘Let them all die.’ Was it the intransigence of Bayezid the Thunderbolt that the duke was thinking of when he later examined the piles of bodies?

A relieved John of Bavaria had all suspicious burghers and noblemen beheaded in Liège or drowned in the Meuse. From then on, he would go through life as ‘John the Pitiless’. He was back in the saddle, but he was also indebted to John of Burgundy more than ever before. The prince-bishopric had basically become a Burgundian protectorate.

The news of the duke’s victory resounded across the European mainland. Some sources even claim that it was this event that earned him the name ‘John the Fearless’. Like his father after Westrozebeke, the duke commissioned the weaving of large wall tapestries in Arras to commemorate the victory. The battle itself was depicted on a tapestry measuring at least seventeen by five metres.

Stone stele marking the battle of Othée

Wall tapestries served an ornamental function, of course, but they were primarily used as insulation in the halls of palaces that were often difficult to heat. They could also be hung as partitions, to divide large rooms into various compartments. Very occasionally they became weapons of propaganda, as the two dukes demonstrated after Westrozebeke and Othée with great panache.

Heaven seemed to reward John’s latest achievement with a eucharistic tribute as well. From then on, he could pray for the souls of the fallen at both Othée (September 23, 1408) and Nicopolis (September 25, 1396) during the same Mass of Remembrance. Whether Othée had wiped out the mistakes of Crécy, Poitiers and Nicopolis remained to be seen. But word spread from Liège to Maastricht, Brussels and Ghent, and all the way to Paris, that John the Fearless was not someone to be toyed with, especially with such a mighty national alliance behind him.

Just when a law was being drafted in Paris stipulating that if the duke dared to dispute his guilt in the murder of Orléans, violence would be used, the news came that Burgundy had won a resounding victory. His opponents, who were feeling very smug, found themselves slinking off with their tails between their legs and leaving Paris to the victor of Othée. On November 25, 1408, the duke made his entrance into the city to the sound of great public acclaim. For the people of Paris, the fact that he was officially persona non grata was like water off a duck’s back.

Forgive your arch-enemy

After lengthy negotiations a settlement was reached, a compromise that managed to prevent a civil war just in the nick of time. On March 9, 1409, Charles of Orléans, the fifteen-year-old son of the victim, was made to publicly offer forgiveness to his arch-enemy John the Fearless in Chartres Cathedral.

The young Charles burst into tears. Heaving with sobs, he forgave the man who had murdered his father. This illusory peace ushered in a period of deceptive calm. John wrote to his brother Anthony that now he could devote himself to ‘the interests of the kingdom’ once again. His victory seemed complete, but it only served to fan the flames of revenge in the mind of Charles of Orléans.

John the Fearless realized he had to be on his guard. He had a twenty-seven-metre castle tower erected at the Hôtel de Bourgogne, the ducal residence in Paris. It was built right against the city wall, to enable him to make a hasty escape. John wanted every room to have a latrine. These oldest preserved toilets in the city were heated and had internal drains, which was quite exceptional. Usually, the waste disappeared through an opening onto the street or into the garden, and you simply had to put up with the filthy smears on the walls.

John made sure his military tower was luxurious and beautiful. The vaulting over the long spiral staircase was of unparalleled splendour – an echo of Champmol in Paris – and because of the quality of the stone it would stand the test of time. Like a glorious, esoteric medieval relic, the Tour Jean-Sans-Peur is still a feature of the busy Rue Étienne Marcel. How many pedestrians would suspect that all by itself, this ancient tower should remind Paris of one of the bloodiest episodes in its history?

John could have walked his murderous path to its logical conclusion by killing the weak-minded Charles VI and declaring himself king. But he didn’t. The mystique of the anointed king was so deeply entrenched in France that even the fearless John of Burgundy would not take such an extreme step. The slowly greying forty-one-year-old wretch, who needed the active assistance of two or three servants to keep him clean, continued to serve as the steadfast embodiment of royal authority.

Although he never laid violent hands on the king, John would wade through blood for years. It wasn’t long before Charles of Orléans, who was consumed by revenge, declared war on Burgundy. There remained only one way for the duke to save his skin: to win this civil war. From now on he would focus almost all his attention on France.

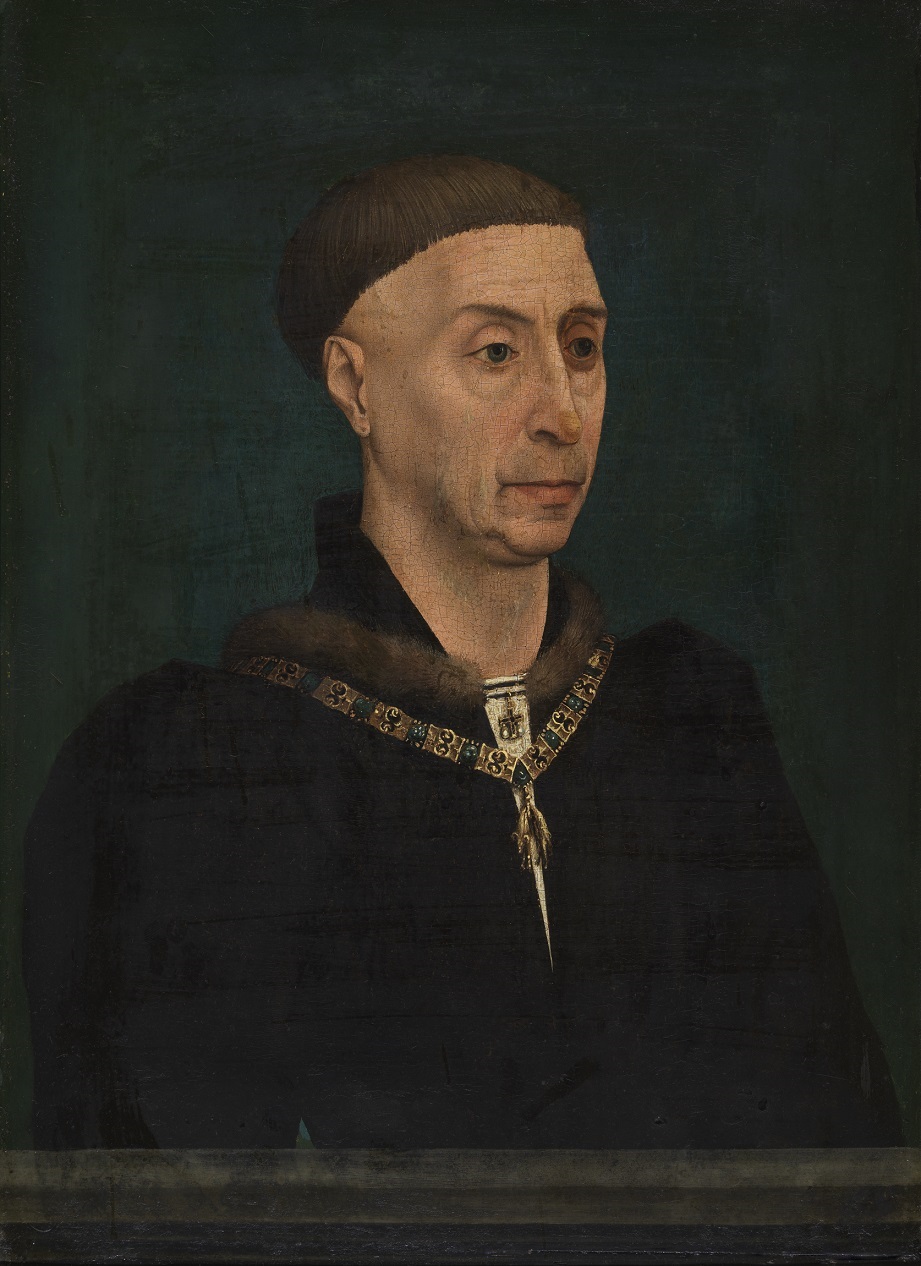

John's son, Philip the Good

In Flanders he installed his fifteen-year-old son Philip as his permanent representative. Philip would move into the Prinsenhof in Ghent in 1411, and three years later he would become the official governor of Flanders – literally the lieu-tenant, the ‘place-holder’, a function that would be given the name ‘stadtholder’ in the regions of Holland.

In collaboration with the Four Members, the young Philip (who officially was still only the Count of Charolais) drew up a balanced international policy and breathed new life into the trade relations with the French liege lord, local partners such as Brabant and Holland, the English wool industry and the German Hanseatic League. During the dark years of the French civil war, any further centralisation of the Flemish-Burgundian state was put on hold. But Burgundy’s centre of gravity had begun its imperceptible journey to the north.

Extracted from The Burgundians: A Vanished Empire by Bart Van Loo which is out now in hardback and paperback, published by Head of Zeus'