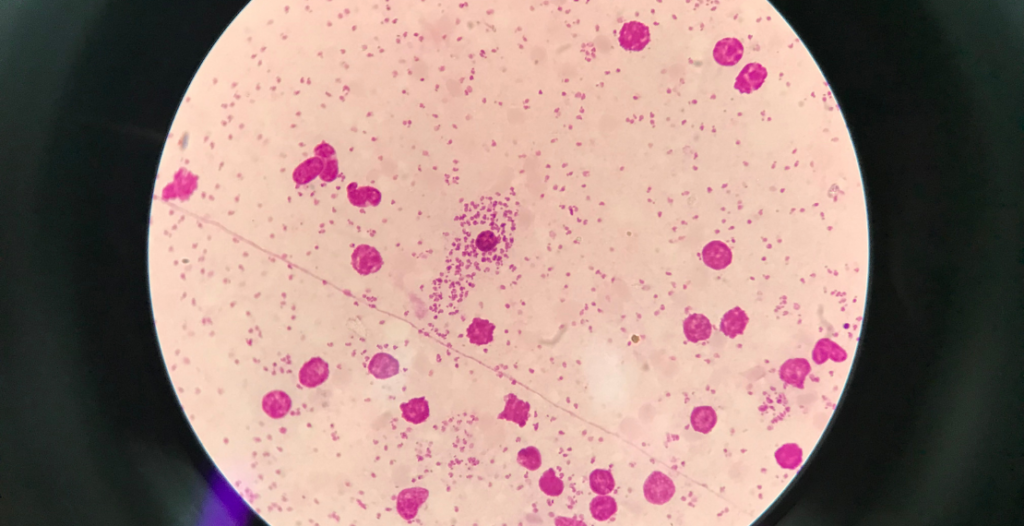

Scientists at the Institute for Tropical Medicine (ITM) in Antwerp have made a breakthrough in their research into a parasite known as Leishmania, which causes an infectious disease carried by at least 93 species of sandfly across the world.

The disease, now known as Leishmaniasis, has been around since the Cretaceous period, according to the fossil record. It was given its modern name after the simultaneous discovery in 1901 by the Scottish Army officer William Boog Leishman and the Irish medical officer Charles Donovan of the Indian medical service.

Leishmaniasis is known to be difficult to treat, because of the parasite’s remarkable ability to change its chromosomal character in response to drugs and vaccines. That talent allows the parasite to escape most treatments, and the disease affects some 300,000 people every year, in 88 countries including in southern Europe.

It is considered one of the most important parasitic diseases in the world, after malaria. But it is also considered a ‘neglected disease’, a group of about 20 conditions including rabies and sleeping sickness which mainly occur in the developing world, affecting those who live in poverty and poor hygienic conditions.

Now scientists at the ITM, using DNA technology, have examined the parasite using single cell genome sequencing. “At ITM, neglected diseases are high on the agenda. ITM conducts clinical, epidemiological and biomedical research activities to fight these diseases,” the institute said in a statement.

“Using a revolutionary DNA technology, called single cell genome sequencing, we were able to 'sequence' each cell separately within one patient's population of cells,” explained Gabriel Negreira, the lead author of the study. They also found individual cell differences within one cell population, a phenomenon known as mosaic aneuploidy.

"We think that each of these cells contains a survival kit for a certain environmental stress,” adds project leaders Dr Malgorzata Anna Domagalska.

“If a certain stress occurs, for example exposure to a drug, the entire population of cells may disappear, except for the one cell that contains the right survival kit, which could then restore the population. Population over individuals, a kind of microbial collectivism."

The phenomenon allows parasites enormous versatility in avoiding and escaping drugs and vaccines.

“We scientists need to be creative and undertake a next step in the arms race against these ‘clever’ parasites,” said Professor Jean-Claude Dujardin, head of the Molecular Parasitology unit at ITM.

“Among other things, we hope in the future to understand the mechanisms of mosaicism and block it. This could provide new avenues for drugs.”