The statue commemorating Gabrielle Petit, the young Belgian woman who spied on the German military during World War I and was executed in 1916, stands on Place Saint-Jean, in the heart of Brussels’ city centre.

Petit is represented holding her chin up in a defiant last stand. “I have just been condemned to death, I will be shot tomorrow. Long live the King, long live Belgium,” reads the plaque which many tourists walk by as they leave the Mont-des-Arts for the Grand Place.

At the Liberation, Petit was “given the equivalent of a state funeral”, Emmanuel Debruyne, a historian who has studied women’s lives and the Resistance during World War I, told The Brussels Times. Her funeral was held on 21 July 1919, Belgium’s national day -- the first one the country celebrated in freedom since 1914.

By the time her statue was inaugurated in 1923, Petit had become a national heroine, and the first working-class woman in European history to be remembered by a monument. Yet through her very active engagement in resistance movements, and through her unique status of national martyr, Gabrielle Petit was the exception, Debruyne said.

Petit, Edith Cavell, Louise de Bettignies and other famous women in the Resistance are rightly remembered for their courageous actions, but in doing so, Belgian history forgets all the other women, he explained.

Women’s roles during war time

Despite the common vision of women embracing new-found freedom in wartime jobs, the lifestyle of most Belgian women was not turned upside down as radically as that of their European neighbours.

“The war deeply shook up the way of life,” Claudine Marissal, a historian at the research centre on the history of women (CARHIF) told The Brussels Times. “But the situation in occupied Belgium was vastly different from France or the United Kingdom.”

German troops marching through Brussels during WW1.

When the Germans invaded neutral Belgium in August 1914, only about 200,000 Belgian men had been called to arms, unlike in France, Germany or the UK, where the vast majority of the male population aged 18 to 45 had been mobilised.

In France, women had to take on almost every aspect of daily life, replacing men in factories and hospitals as well as managing home duties. But because in Belgium only around 20 percent of the country’s male population went to the front, “the role of women in society was less altered than elsewhere,” Debruyne said.

The economic situation, however, was disastrous, with skyrocketing unemployment and food shortages, especially in urban centres. “In 1917, nearly the entire Belgian population resorted to humanitarian aid,” Marissal said.

“Men and women alike found themselves in deep precarity, in a reverse situation from neighbouring countries where women took over men’s jobs. There was a sense of gender equality before the suffering.”

Male domination

Yet in this crumbing economy, the few jobs that were left “mostly went to the men,” Debruyne explained, effectively rendering the vast majority of women unemployed.

Feminist groups who before the war were petitioning for women’s suffrage turned to social work, founding the Patriotic Union of Belgian Women to give small jobs to women. New professions developed as well: nursing schools, which had opened before 1914, grew exponentially, offering women job opportunities.

But in schools or in hospitals, women’s professional choices were reduced to positions close to their traditional role of mother, carer or housekeeper. The women who could not find work sometimes turned to prostitution.

In Brussels, prostitution exploded, as did the number of children born of unknown fathers, due to the rapes that women suffered from German soldiers during the invasion in 1914.

“Women were dominated in every way: the domination of the occupier towards the occupied, of men towards women, of the military towards civil society,” Debruyne said. “There was an intersectionality of domination, which made figures such as Petit even rarer, and more difficult to emerge.”

Female resistance agents

An exhibition on the life of women during World War I organised by Belgium’s Museum of Resistance and Amazone NGO in September 2019 shone a light on women who exemplified themselves during the war – through resistance networks but also other patriotic commitments in nursing and charity work.

The British nurse and MI6 agent Edith Cavell, who was executed by the Germans in 1915 and, like Petit, became a post-war martyr figure, played a strategic role in evasion networks, helping soldiers to cross the border to the Netherlands.

In Cavell’s network also worked Marie de Croÿ, who later played a role in the resistance in World War II. The Frenchwoman Louise de Bettignies launched a vast intelligence network throughout Belgium and northern France and spied on the German army until she was arrested in 1915.

These women, more emancipated and active than most, were autonomous and able to act in part due to their celibacy, Debruyne observed: “They were not under a man’s tutelage, nor had the burden to care for a family.”

Being female in the resistance could also work as an advantage: “In some networks, women were used as liaison agents because the Germans were less wary of them.”

The exhibition mentioned lesser known, everyday life heroes, too, like Madame Tack, a widow from Nieuwkappelle nicknamed ‘the soldiers’ mum’, who resupplied the troops despite the bombings; Hélène Dutrieux, who worked as a nurse and ambulance driver after training as a pilot; or Mieke Deboeuf, from Dixmude, who lost her house to German shells but continued to offer her help to soldiers.

Resistance in occupied Belgium took many forms – active resistance was only one of them. Debruyne, who has profoundly studied the topic, sets apart three kinds of resistance networks whose actions depended on each other: some provided intelligence on German troops while others organised the (forbidden) correspondence with the front or facilitated the evasion of foreign soldiers to the neutral Dutch border.

Women took part in all three activities in uneven numbers, but the majority of resistance networks members were men, Debruyne noted.

In intelligence, for instance, women accounted for 20 to 25 percent of the 6,500 active agents in Belgium and northern France. He estimates that among the 10,000 resistance agents he has studied in his research, at least 3,000 were women – of which 2,000 are named in resistance networks files.

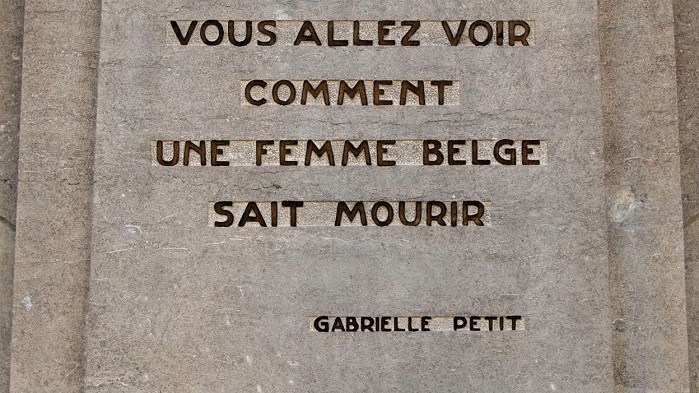

“You will see how a Belgian woman knows how to die.” Commemorative statue and plaque for Gabrielle Petit who became a Belgian national heroine after the war ended.

But despite the fiery memory left in history books by Gabrielle Petit, there were few female spies. Women were also absent from clandestine press circles.

They were, however, more active in evasion and correspondence groups, Debruyne said: “The humanitarian character of these forms of resistance was closer to the gender characteristics that society attributed to women at the time, such as care or dedication.”

Collecting intelligence

The traditional role of women within the family, reinforced by the dire war situation which left most at home, could also play a pivotal role in the resistance.

“For women, commitment to the resistance heavily relied on another member of her family being involved,” Debruyne explained. Sometimes, the entire family contributed: in intelligence networks, information on rail was crucial to understand where the German army was moving and roughly calculate their numbers and weaponry.

Along rail lines, locals involved in passive intelligence resistance kept watch from their home, Debruyne said: “And who best than a family to take turns at the window without raising suspicion?” In these extremely important positions, the resistance counted “a great proportion of women”.

One family, among many anonymous ones, is well-known: that of Thérèse-Marie de Radiguès, who brought her husband and daughters into the Dame Blanche intelligence network, which she had co-founded in 1916 with fellow resistant Walthère Dewé.

The network, by far the biggest of the Belgian resistance, was made up of 30 percent of women, Debruyne said, and had developed an “alternative feminine structure”, so as to keep running with female-only operatives in case male agents would be called to arms.

Dewé’s vision of the Dame Blanche hierarchy was “very gendered”, Debruyne explained: “His own words were: ‘It’s up to the men to lead’.” The role of women in the group was to act as a reserve in support of male members, just as a wife’s duty was to support her husband.

This did not prevent Thérèse de Radiguès from being very active in the network and beyond: she joined the resistance again, at 75, in 1940.

After the war, Belgian women found themselves in a paradox. At the Liberation in November 1918, King Albert I spoke of “equality before pain and endurance,” yet announced that “adult men of all ages” – only men – would be granted the vote. This, Claudine Marissal said, was felt by women as an erasure of their own wartime suffering.

In 1919, only widows and female war heroes were granted the vote – more as a “replacement vote for the dead” than real suffrage, Marissal noted. “History books remember the figures of women in the resistance, Gabrielle Petit and Edith Cavell, or the figure of the nurse.

But after women committed their work and help alongside the men’s to manage the immense suffering of the war, only men obtained political progress after the conflict,” she said. For their own emancipation through the vote, women would have to wait another 30 years.

By Pauline Bock