A trainee who completed a six-month unpaid internship with the European External Action Service (EEAS) at its delegation to the UN in Geneva said that he had lost 7kg of his body weight during his internship.

The reason? Spaniard Pau Petit, 27, said he could not afford all the food he needed.

“With other intern colleagues, we went to as many receptions as possible where we could eat the leftovers for free. But sometimes they would kick hungry interns out,” he said. “My hope is that all interns will be paid and their legal status recognised, including health insurance and other basic rights.”

"The EEAS also make you sign a contract which says they are not responsible for any problems you may run in to," he added. Petit said he had worked for half a year without being paid or insured.

With an estimated 8,000 young people undertaking internships in the EU institutions each year, the uneven treatment facing them was highlighted when many of them organised a protest in Brussels last February. Growing demand for fair play was also reflected recently in a decision by the European ombudsman, Emily O’Reilly, who ruled that the EU should start paying all its trainees at delegations abroad.

Internships are intended to facilitate the transition between education and employment for young professionals. But campaigners say the lack of clear rules and a legal framework in some countries very often leads to confusion and malpractice. Belgian legislation covers most types of internships, from mandatory to voluntary/volunteer internship placements, but is not always followed.

The Irish-born Ombudsman judged that the current practice of unpaid internships unfairly favoured a privileged few. The ombudsman, who investigates complaints at EU bodies, said that the EEAS employs some 800 unpaid trainees at its delegations worldwide, out of a workforce of about 2,200 people.

"The trainees must cover all of their costs including accommodation, travel and health insurance, a system which clearly discriminates against many young people with limited means," the Ombudsman wrote. Her probe was sparked by a young Austrian woman who had worked as an unpaid intern at an EU delegation in Asia.

An EU spokesperson responded, telling The Brussels Times, “As noted by the Ombudsman's assessment, the EEAS has taken steps to address several of the issues raised in the investigation, in particular concerning information on traineeships for candidates.”

The spokesman went on, “Regarding the financial aspect that has been raised by the Ombudsman, the EEAS will now assess and review the scheme for unpaid traineeships in delegations, including its budgetary dimension.”

The recent focus has been on the EEAS, but what about the other EU institutions? In 2016, the European Parliament recruited 118 candidates under its training placement scheme. It also hired 505 university graduates. The Parliament has banned unpaid internships in its secretariat, but MEPs are still free to propose such internships in their offices.

The Parliament distinguishes between “graduate traineeships” and “standard” or “educational” traineeships. The graduate traineeships are for students who have already obtained a degree, whereas the standard traineeship usually forms part of a curriculum. A traineeship can last from 2-5 months depending on the type of traineeship.

The traineeships for graduates are remunerated with a scholarship. The educational traineeship trainees receive €300 per month as a contribution to living costs. A 2013 survey by the Parliament’s Youth Intergroup showed that about 20% of the interns in the Parliament were paid less than €300 or were not paid at all. Only 22% were paid more than €1,000.

As for the European Commission, it recruits around 1,300 trainees (stagiares) per year through a five month-traineeship programme. These interns receive a monthly grant of about €1,100, reimbursement of travel expenses and health insurance.

In addition, General Directorates in the Commission may decide to accept non-remunerated trainees for periods of 2–3 months. There were 200 unpaid trainees on 1 June 2016 according to the figures from the Commission.

Terry Reintke, a German Greens deputy, said that the conditions faced by unpaid interns in Europe face are unacceptable. Reintke, the youngest female MEP in the parliament, said that unpaid work allows inequality to grow because it discriminates against those from lower economic classes.

“Who can actually do these internships? If you think about it, many people who might not come from such well-off backgrounds cannot afford to do unpaid internships in the European institutions.”

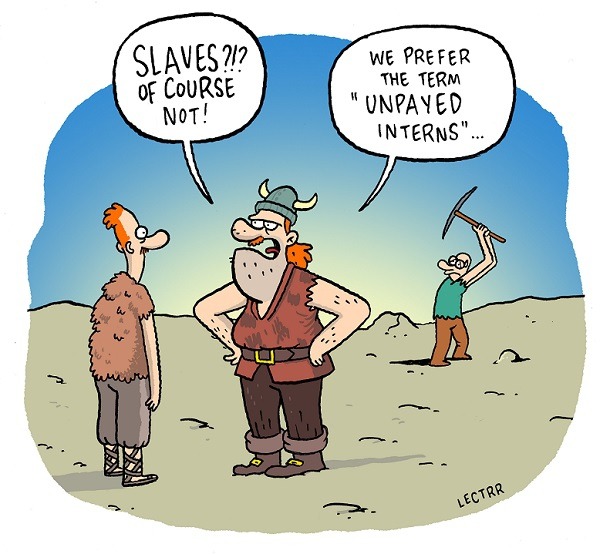

Interns, students and young professionals protest in Brussels against the practice of unpaid internships.

“Especially in the current situation, where we are faced with incredibly high youth unemployment rates, this creates a situation where many young people are so desperate that they would do anything just to get a perspective.”

“Whether or not young people get the opportunity to experience work at an EU institution cannot depend on the wallets of their parents. This is also what the European Ombudswoman has pointed out in her ruling: By not paying for an internship, some people are directly excluded from the opportunity to even do such an internship, as they won't be able to cover their living costs.”

She called on all European institutions to abide by the legal standards that apply to the place where the internship is performed. In other words, they should have a right to Belgian minimum wage, which also applies to interns in Belgium.

Scottish Socialist MEP David Martin said, “Unpaid internships are drivers of inequality, offering opportunities only to those who have enough financial support or the right connections.”

“Generally, the EU institutions’ internship scheme is good compared to other international organisations, but EU’s delegations abroad are clearly a blind spot, and I’m glad the Ombudsman has highlighted this. At a minimum, internships should have an open and transparent recruitment process and get paid a living wage.”

“Unpaid internships discriminate against people from poorer backgrounds, widen social inequalities, undermine the tax system and create a culture where employers do not train their staff, seeing no reason to invest in them,” says Bryn Watkins, managing member of Brussels Interns NGO.

Watkins added, “The moral case against unpaid internships has been won, and it is great to see that employers are beginning to wake up to that. However, there is still far too much hypocrisy in the EU institutions, which claim to fight for young people while also taking hundreds of unpaid interns every year.”

The hungry intern Pau Petit mentioned in the beginning of this article has taken part in several global protests by unpaid interns not only in Brussels but also in other cities including Geneva, Vienna and New York. The problem, clearly, is not confined to the EU Bubble. While the EU ombudsman's recommendations are not legally binding, interns now hope that her advice will be followed.

By Martin Banks

| Findings of survey on internship conditions in the European Parliament (conducted by the European Parliament Youth Intergroup) - Average age of interns: 24 - 80 % work for an individual MEP - For 83 %, the internship is not a formal part of education - Only 4 respondents (1,72%) don’t have a written internship agreement - Only 22% have a learning agreement or written learning objectives - 17.18 % don’t get any compensation - 3.09 % receive less than €300 - 20 % receive €300-600 - 37 % receive €600-€1,000 - 22 % receive more than €1,000 |