In October 1958, amid the modernist fever of optimism at the culmination of the Brussels World Fair that year, the architect Stanislas Jasinski spoke at an exhibition on proposals to redevelop the city’s North Quarter.

It took place at the newly opened International Rogier Centre in the square of the same name. The Urbanisation and Rebirth of a Neighbourhood event floated plans for a total rebuilding of the area, blighted by the demolition of its centrepiece, the ornate 19th century North Station, now replaced by the venue itself. At 57, Jasinski had reason to be satisfied by both the location and the content of the exhibition. They showed that others were fulfilling dreams he had held for Brussels for over three decades.

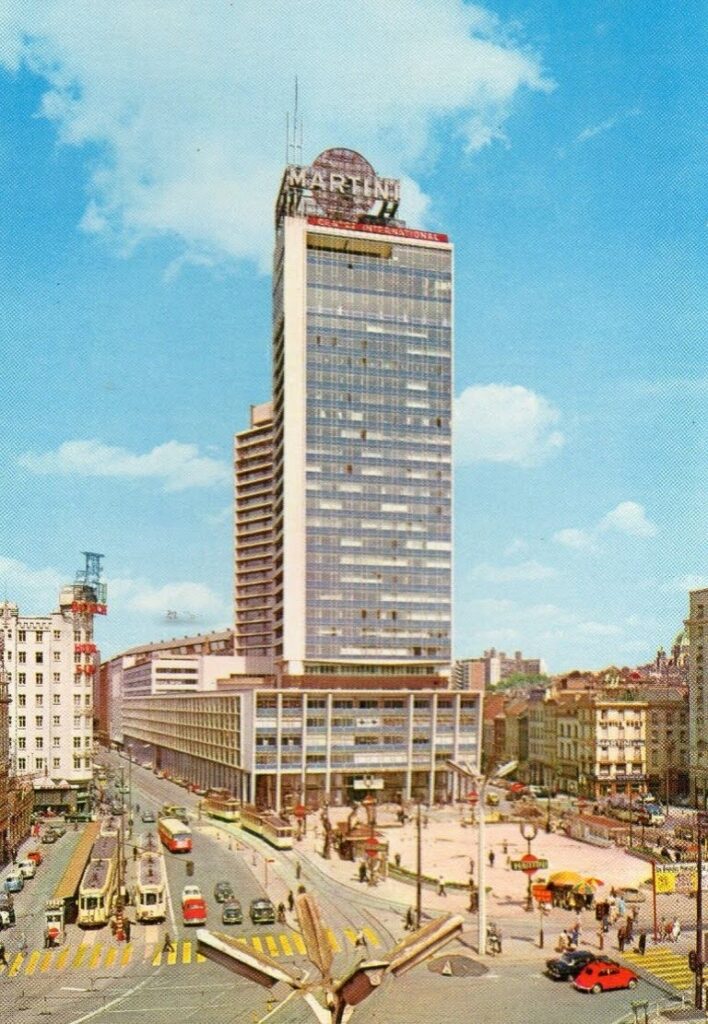

Facing the entrance to the Brussels central boulevard, the 29-storey tower of the Rogier Centre, was topped by a giant Martini ad hoarding that gave it its nickname. At 117 metres tall, this flagship of Belgian modernism in glass, concrete and aluminium took the place of the stone facade of the old station, rendered obsolete by the new rail link through the city.

Inside the Martini Tower were restaurants, exhibition spaces, two theatres, a shopping centre in the plinth at ground level and a prestigious bar on the top floor, the Martini Terrace. Behind it, stretching 260 metres to the north were two blocks, one containing 151 luxury flats with terraces and the other offices.

The International Rogier centre

Rogier was to be the anchor development in a 53-hectare urban renewal programme stretching as far west as the Brussels canal. Rebranded as the Manhattan Plan in the 1960s, it aimed to replace a dense grid of decaying 19th century low-income housing with dozens of towers set on plinths. Pedestrians were to pick their way between them on elevated walkways as motorways from Amsterdam and Paris converged beneath their feet at the “Crossroads of Europe”.

A global debate

Not even half-completed, the scheme fell apart over agonising decades in a mire of corruption, mismanagement and failing economic cycles. Some 11,000 people lost their homes and by the beginning of the 21st century, the rebirth of the North Quarter was seen as a massacre, a national disgrace and the worst excess of Brusselization. The remaining old buildings blighted the new ones and the new blighted the old. Poorly maintained and abandoned by residents, the Centre Rogier was tarred with the same brush and pulled down in 2002.

Jasinski didn’t design the Rogier Centre. It was the work of two younger Belgian architects, Jacques Cuisinier and Serge Lebrun. Embedded within its design and that of the Manhattan Plan however were concepts of urban renewal Jasinski had popularised in articles and projects stretching as far back as the 1920s.

In 2024, as a fresh rebirth for the North Quarter takes shape, CIVA, the Brussels region’s architecture museum is holding its first exhibition on the Jasinski. He is best known as a prolific builder of cosseted apartment blocks in greenfield locations in the outer suburbs. However, CIVA’s show, entitled ‘Stanislas Jasinski, The Modernisation of Brussels’, presents his unrealised designs for the city centre, concepts he never got to build but which, as at Rogier and in the Manhattan Plan, took on form in the work of others.

Jasinski’s designs are displayed alongside realised and unrealised projects by architects from Belgium and across the world. They anchor him within the context of a century-long global debate on how planners and architects should create cities amid the economic and technological evolutions in which they are both actor and spectator. A debate in which Jasinski took part over six decades and which, like his own career has been discredited by the spectre of Brusselization.

Creative destruction

Jasinski had made his name from the 1920s onwards in articles calling for a tabula rasa in both the architecture and urbanism of Brussels. “As a rule, people are happier living in apartments,” he told the journal Bâtir in a 1936 interview entitled Detruire pour Créer (Destroy to Create). “In city-centre flats on the 14th or 15th floor...we will breathe clean air. We will reach them by express lift, we'll have hot water and ice on demand. We'll be able to have lunch delivered in five minutes. Thanks to the obligatory terrace, we'll enjoy splendid panoramic views".

Twenty years later, this was the experience of the first wealthy residents in the curvy residential ‘banana’ section of the Rogier complex, gazing over the Botanique gardens to the east and westward to sunsets behind the Basilica at Koekelberg.

The path to such airy, sunlit, healthy homes was explained by Jasinski in a series of articles at the turn of the 1930s where he set out his concept of Brussels as a living organism “whose life is regulated by the free play of the fluids.”

The city was like, "an old tree trunk whose sap only nourishes the ends of its lower branches, while its new growth rots and dries out the centre." This rot included the architecture of the past: “We need to leave behind an urban decor, which has had its time”, to be replaced with designs based on “logic, rationalism and standardisation… [which] in no way rule out modern architectural beauty,” he wrote. While he grudgingly accepted the need to preserve the tourist magnet of the Grand Place, the rest of the older fabric that “besmirches” the city had to go, including the then very recent “aesthetic experiments” of Art Nouveau.

His planned towers on plinths connected by walkways

Mixing a fresh organic metaphor, the human body, with particular hobbyhorses of his, free-flowing traffic and towers, Jasinski prescribed "a bloodletting to ease congestion, new arteries, car parks, pedestrian walkways and increased population density in the centre, thanks to tall buildings on wide thoroughfares.” Step one, the “bloodletting”, was to be the transfer of low-income housing outside the city. Step two was to set aside the sticking plasters of one-way streets and parking bans and prepare the patient for “major surgery” to allow fast circulation of cars.

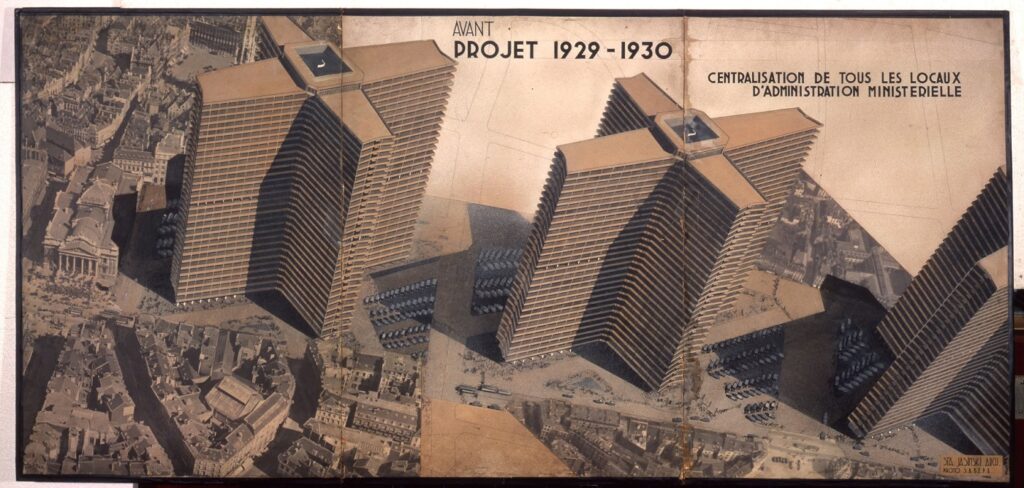

At the entrance to the CIVA exhibition is a vast 1932 photomontage to illustrate his proposal to flatten seven city blocks along a 500-metre stretch of the 19th century showpiece central boulevard in Brussels. Excising centuries of built heritage, including the baroque church of Notre-Dame de Bon Secours, the ‘improvement plan for Central Brussels’ replaced it with three gigantic X-shaped office towers to house Belgium’s civil service in an ‘administrative city’. An irrepressible petrolhead and self-publicist, Jasinski paraded this very same surgical plan around the city on top of his car.

Jasinski's 1930 plan for Brussels administrative buildings

While his proposed parade of towers next to the Bourse never happened, as so often in Brussels their design took hold in the collective imagination of developers and architects. Giant X-shaped structures replaced entire city blocks decades later in the forms of the Monnaie and Berlaymont buildings.

Hive mind

The walls of the exhibition itself are lined with further Jasinski designs. A stunning skyscraper set on a plinth from 1926 anticipates the towers and walkways of the Manhattan Plan. A 1936 study for a 30-storey tower on Avenue Louise could trick image recognition software into thinking it is the UP-site tower on the Brussels canal inaugurated in 2014. There is a 1972 plan for residential and office towers set upon a plinth covering a new metro station in Uccle, back when such a thing still seemed possible.

None of Jasinski’s designs appearing in the exhibition were built, however, and his many projects that were completed only appear in the accompanying book. This is an exhibition of the imagination and counterfactuals, of absences and partial presences. It focuses not on the originality of ideas but of their place within an intellectual continuum of both provocation and pragmatism, stretching the boundaries of urban possibilities. Le Corbusier’s famous 1925 Plan Voisin project for replacing the historic right bank of Paris with a thicket of tower blocks is here, an obvious influence on Jasinski’s later riff on this for Brussels.

Such complexity explains why it has taken until 2024, 46 years after Jasinski’s death to produce a major exhibition on the man who was once “the rising star of Belgian modernist architecture,” the organisers say. The diversity of his activity (he was a furniture designer and real-estate developer as well as an urban theorist and architect) complicated the task, as did his lopsided catalogue.

One of Jasinski's realised buildings, Le Tonneau (The Barrel) an apartment block in Ixelles

In the run-up to World War II, he designed or co-created arresting, tall avant-garde flats in the inner suburbs. His postwar output largely consisted of sprawling and tubby apartment complexes in former country estates in Uccle. But he remained an energetic commentator on the renewal of the urban core until the 1970s, when his name cropped up as the subject resurfaced again and again.

Postwar rehabilitation

The exhibition is in part a rehabilitation of both Jasinski and, by extension, the messy postwar trajectory of the city, plastered with the catch-all Brusselization jibe. It’s true that he argued for the warehousing of the poor on the edge of a city, their homes making way for rapid car travel and that this happened to some extent. But he was also an early champion of dense, mixed-use urban blocks and an extensive metro network. And in terms of planning policy that’s where we are now, for better or, as some still argue, for worse.

The Rogier Centre embodied much of Jasinski’s vision for city centres. It probably wouldn't be demolished now, as such environmental wastefulness is frowned upon. With its mixed-use nature and modernist cool it could be a poster child for a car-free existence where shops, jobs, culture and human company are steps away. Terraces really are obligatory now and rooftop terrace bars are all the rage. In that sense at least, the Rogier vision survives and it could comfortably slot into this exhibition, as another counterfactual, another absence as well as an actual memory for some.

Perhaps we can detect steps towards the wider rehabilitation of the architecture of the offices and postwar apartments that ring Brussels. In aesthetic terms, not just those of the make-do-and-mend concerns of sustainability. Only eight buildings from the 1950s and 11 from the 1960s are protected in the Brussels region, compared to 65 from the 1920s and 43 from the 1930s. Either design quality dropped off a cliff after World War II or we are still growing into it. The growing number of listings for more recent buildings suggests the latter.

Public taste has always run a few steps behind the bulldozers of speculative capitalism but exhibitions like this suggest it may be accelerating. Recent protections for the 1960 Banque Lambert (present at the Jasinski exhibition) and Royal Belge building of 1965 have been well received in the media and in the coming years attitudes to others may soften as they limp into octogenarian status.

Respect the past, create the future has been the mantra of the Brussels government in recent years. Stanislas Jasinski scorned the former but as the exhibition demonstrates, he played his part in the latter, so we can respect that at least. And perhaps the next Jasinski expo will proudly show what he actually did build instead of leaving it in the pages of a book or hidden behind the leafy boughs and security gates of Uccle.