Imagine: you're naked, you're on stage in a big tent. Not only is the tent filled with fully clothed people watching you, but they are all laughing, jeering and drinking. Many of them are also throwing sticky wads of blue goo at you and the other 18-year-olds.

You’ve been told to act out scenes while songs are played through the speakers. You are trying to focus on the moves, but with every step, you are reminded that you are naked, on display for everyone in the tent to see.

This is not a bad dream. This is a standard student hazing ritual at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), or the Free University of Brussels. And while it may be hard to believe people voluntarily sign up for hazing – also known as initiations, baptisms or ‘bizutage’– many first-year students do exactly that every year.

Hazing rituals for fraternities, sororities and student societies are common around the world, but Belgium’s tend to be more extreme. While some involve relatively harmless pranks, others might be characterised as humiliation, abuse and even criminal.

The VUB’s naked performances are far from the worst that students might face. In 2018, Sanda Dia, a 20-year-old engineering student at one of Belgium’s most prestigious universities, KU Leuven died after a notoriously vicious hazing which involved chugging fish oil until he vomited and sitting naked in an ice-filled trench. His death sparked a reckoning at universities, with students increasingly pushing back against hazing.

Hazed and confused

But back to the VUB, where hazing, is still popular. J, a VUB alumnus lived them, at least the stripping on stage and being pelted with blue goo. He says he is glad he did and would probably do it again now, years after he’s graduated.

“Hazings and student clubs, and to some extent even student life in general, have acquired a bad reputation in recent years: drinking to excess, gratuitous humiliation and extreme rituals,” he says. “Some student clubs definitely go too far, but they are not all like that.”

ICHEC students on the Brussels streets during hazing season

It was an open secret that the hazing ritual of the student club J. sought to join, the VUB's Psycho-Educational Circle (Psycho-Ped'agogische Kring – PPK), involved “a lot of nudity,” but that wasn't an issue for him, he explains. "Being hazed, for me, was about pushing and even breaking certain boundaries that had been set by my environment and my parents, including being naked in public, for example."

He also acknowledges that another part of his decision to enter the student club was his search for belonging. "You're a young student in your first year of a bachelor's programme and you're looking to be part of a group. You're fresh out of secondary school and kind of tasting your freedom as not-quite-an-adult. In a way, it also made me feel secure: the club had fixed activities, so I was sure I'd have friends and a social life."

While these clubs are purposefully structured in a militaristic fashion, with a clear hierarchy between senior members (such as the chair of the club, called a ‘praeses’, from the Latin word for "at the head") and those wanting to join (called 'schachten') to create a strong group feeling among the new ones, not all clubs are the same. "The PPK is a very 'soft' club, so to speak. I definitely do not regret that I took part in the hazing, but I never would have joined one of the other clubs."

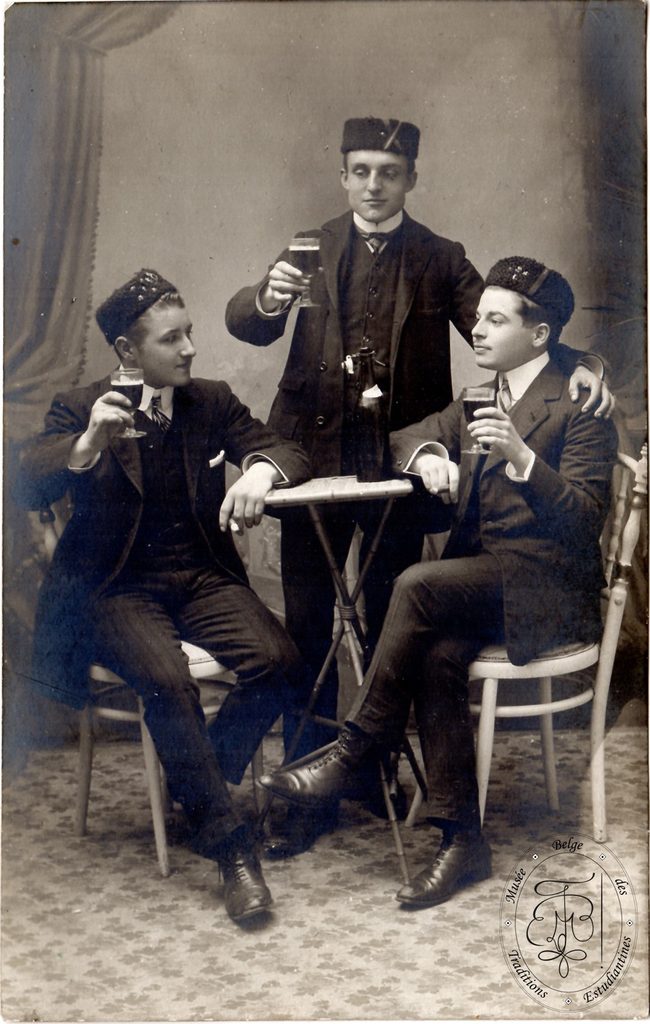

Turn of the century fraternity

J. explains that, while nudity was required for the men taking part in his club’s hazing, women were allowed to keep on a pair of underwear if they felt more comfortable like that. “Society doesn’t regard women’s bare breasts the same way a man’s naked torso, so by going shirtless, women already revealed more than the men did and they could opt to stop there.”

All VUB faculties' hazing rituals are the same, but this, he says, was a very important factor for him to feel safe because it showed that the PPK was following the official rules drawn up by the VUB’s umbrella student association, the BSG.

It may not seem like much when you’ve already taken off all your other clothes to then be put on stage and expected to perform a play, but J. says few clubs make concessions like that. “Not all universities had such rules at the time, which is also why some initiations got so out of hand,” J. says.

"My glasses may be a bit rose-coloured because of my good experience with the initiation and the club in general, but I am aware that this has not been the case for everyone,” he says. “A lot depends on the framework in which the rituals take place and the group dynamic you want to obtain. I do not think hazings in themselves are good or bad. I just think clear rules are needed.”

That group dynamic and lack of rules, however, made headlines in Belgium and beyond. More and more stories have emerged about hazings gone wrong as students behave obscenely and inappropriately – with even former British Prime Minister David Cameron alleged to have had sex with a dead pig, in an incident dubbed ‘Piggate’.

A ticking time bomb

It all came to a head in Belgium with the death of Sanda Dia from a hazing with the now-disbanded male-only Flemish student club Reuzegom – home to the scions of Antwerp’s (white) elites.

The unsanctioned club was filled with the sons of judges, business leaders, lawyers and politicians. One student who was hazed alongside Dia but no longer wanted to join the fraternity afterwards said that Reuzegom asked “how big the driveway of your house was, what kind of car you had, whether there was a swimming pool and what your father did and earned” before considering a new member.

Students paying tribute to Sanda Dia and protesting against hazing in Ghent

Kenny Van Minsel, who was president of the campus student association at the time of the hazing, said that he repeatedly – and unsuccessfully – urged Reuzegom to sign the university’s hazing code of conduct, called the Doop Charter, in which clubs agree to a set of rules to abide by when initiating new members to ensure everything happens safely.

However, as the club was not officially recognised and belonged to no national umbrella body, Van Minsel could not force them to sign the charter – and they didn’t. For him, Reuzegom was “a ticking time bomb.”

What brings an extra element to Dia’s death is the fact that he was of mixed heritage: his father, Ousmane Dia, was black and arrived in Belgium as an asylum seeker from Senegal in 1994. Ousmane Dia, a searing presence at the subsequent trial of the Reuzegom students, said his son took part in the hazing rituals as he was simply trying to fit it.

Sanda Dia in Berlin

Did the other student pick on him because he was clearly an outsider? Reuzegom was not described as white supremacist, but Van Minsel said its members were “predominantly white – that’s a given – and predominantly upper-class.” And although there is no evidence that there were any explicit racist motives or that Dia was killed intentionally, he was the only one of the three students who was black, and the only one who died.

Too little, too late

As part of the two-day fatal hazing, Sanda and the two other pledges were forced to drink until they passed out. Investigators later discovered a video showing fraternity brothers urinating on them. The following morning, the pledges were taken to a cabin in the woodsy town of Vorselaar, outside Antwerp, where they were forced to dig a ditch and stand in it as it was filled with ice and cold water. All this took place on a cold December night.

They were then made to swallow whole goldfish, eat a blended-mice-and-eel porridge, continue drinking alcohol and chug fish oil. As they were let out of the pit one by one, Dia was kept in the ice the longest until the other pledges dragged him out. Photos show him lying in the foetal position on the grass.

He was eventually taken to hospital where he died two days later of hypothermia and multiple organ failure. His death was seen as a tragic accident, an example of hazing gone wrong, and led to widespread social outrage, which only grew as details of the initiation became public.

Nearly two years after Dia’s death, all 18 Reuzegom members present that December night were tried for administering harmful substances, unintentional manslaughter, degrading treatment and refusal of assistance due to guilty negligence.

Sanda's father Ousmane Dia pictured after the judgement of the court in the trial against the 18 members of the Reuzegom students club

The trial was delayed several times due to the Covid-19 pandemic, requests for additional investigations, and strikingly, after it emerged that a judge at the Antwerp court had a family link with a member of Reuzegom (the investigation was transferred to the Limburg public prosecutor's office). On May 26 this year, the Reuzegom members were finally found guilty of unintentional manslaughter and degrading treatment – but not for administering harmful substances or guilty negligence.

Though they will all avoid prison – prosecutors sought jail sentences ranging from 18 to 50 months - they have been handed up to 300 hours of community service (which critics have compared to a student internship) and a €400 fine (described as “spare change” for the sons of the so-called Antwerp elite).

No more Sanda Dias

Dia’s death came at a critical moment, says the president of the Flemish Union of Students (VVS), Julien De Wit. “We have seen that the rituals tend to become more and more extreme every year as those who have been hazed feel the need to be even tougher on the next generation of pledges,” De Wit says.

However, the outcry and the trial changed how universities see hazing. “Many people would just like to do away with the entire hazing business,” De Wit says. “While I understand where they are coming from, I don’t think that’s the solution at all. That will just lead to everything continuing to happen, but under the radar where there is no supervision at all. That will only lead to more Sanda Dias.”

The VVS has tried to address the issue with a new Hazing Charter. While not mandatory, it aims to guide those planning an initiation ritual for their club. “They can use it as a guideline to look at what the group dynamics in a club are like, what good practices are, and what they need to work on. We wanted some kind of document that you, as a club, can refer to every now and then to keep yourselves on track,” he says.

The Sanda Dia tragedy could finally mark a tipping point in the initiation culture, which students and university authorities had allowed to spiral out of control. “Reuzegom's hazing was an escalation of things that got worse and worse every year,” De Wit says. “It was totally unheard of for anyone to say, ‘Hang on, maybe this is too far, maybe we shouldn’t do this.’ But we hope this guide offers a reality check so people can do exactly that.”