Utopia is now getting renewed attention – in the city of Leuven in Belgium and far beyond. This book has an important connection with Leuven. It is now exactly 500 years ago that this influential publication was printed in the workshop of Dirk Martens in Leuven, opposite its well-known University Hall. The most important part of the book, the description of the imaginary island of Utopia itself, was already written in 1515 during Thomas More’s visit to Flanders.

Another important link with Leuven is More’s friendship with the humanist thinker Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam, who lived and taught at the university in Leuven from 1517 to 1521, just after the book was published by Dirk Martens.

Printing in Leuven

In the year 1515, More was part of a high diplomatic mission in Flanders. From May to December he stayed in Bruges. Charles of Castile (the later Charles V) initially planned to marry the sister of Henry VIII, but for political reasons the eldest daughter of the French king Louis XII seemed more suitable.

This was answered with a ban by the English Crown on the export of wool to the Low Countries. As this turned out to be highly detrimental to the English economy, rapprochement was sought. This was precisely why More was sent as part of a delegation to negotiate with the representatives of Prince Charles. When the consultations fell silent or took a break after a few rounds, he visited a friend, Peter Gillis in Antwerp. Gillis was city secretary in Antwerp.

There he wrote the main part of his book. During his stay, he also visited Brussels and Mechelen. More wrote the introductory part of the book, when he was home again. There is a clear logical link between the two parts. The first part can be described as an analysis of the problems in English society of that time, while the second main part outlines the remedy for the illnesses of society in the form of the imaginary island Utopia – a Greek word meaning “No Place”.

The corner in Leuven today of the workshop of Dirk Martens, where Thomas More’s book was first printed in 1516

In 1516, Dirk Martens in Leuven printed the book. The printing house was located at the corner of Naamsestraat and Standonckstraat. The printing was probably the result of a combination of factors. The Low Countries had freedom of press, and More, despite his good relations at that time with the king, might have feared negative repercussions in England.

He might also have thought that the book would be more appreciated in the political climate in the Low Countries or perhaps he thought of Dirk Martens as the most adept printer. We cannot know for sure. The fact is that he sent the manuscript to Erasmus who personally overlooked the printing. The book was published in Latin and only in 1551 was an English translation published.

Content of the book

In Utopia, More brings the fictional figure Raphael Hythlodaeus unto the stage. He claims that Gillis introduced Hythlodaeus to him in Antwerp. Hythlodaeus is a mysterious explorer who had sailed with Amerigo Vespucci to America. Raphael is also the saint of travellers, and Hythlodaeus in Greek means something like “speaker of nonsense”, an indication perhaps that the book should not be taken too seriously.

Somewhere in the New World, Hythlodaeus encountered an island that, according to him, represented an ideal society. The book is basically a critique of the fundamentally unjust and cruel social conditions in Europe in the 16th century, not the least in More’s homeland.

In Utopia, a strong influence of Christian and classical virtues and concepts can be noted. The description of the Utopian institutions and laws – although there are surprisingly not many laws in place besides a constitution, and lawyers are not needed in Utopia – draw on famous ancient works on political philosophy by Plato and Aristotle.

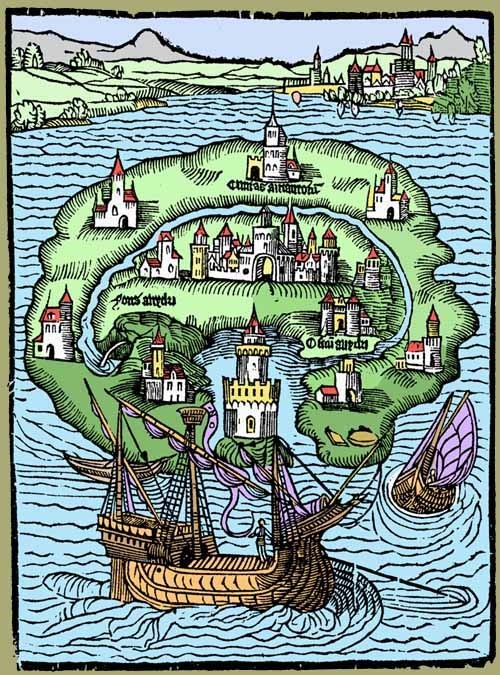

The island of Utopia, according to the first print of the book

Although all material needs are provided for in Utopia, life there feels very monastic and dull, without personal freedom, and is probably inspired by More's stay as a child at a monastery.

Utopia is the first book in the history of literature that outlines an organized welfare state. In return for six hours of manual labour per day in agriculture and a chosen craft, a lot of uncertainties in the Western world (then and now) are cleared. Agricultural work is divided equally among all citizens and provides food to the cities. Everyone lives safely within city walls and receives for his and her labour the same food, clothing and housing. There is no room for any fashion in Utopia.

This is totally different from the system of enclosures in More’s England, where agricultural land was appropriated for wool production, which disadvantaged the majority of the population. Utopia is a society without private property and money. Everything is distributed from public warehouses according to the needs in society. Communal meals, entertainment and religious services are provided in each city.

In Utopia, there is room for everyone's mental and intellectual development within the limits of a strict family and marital ethics where divorces are not allowed without permission, and adultery may be punished by slavery. In hospitals, the sick are cared for with love and attention. Euthanasia is possible and even encouraged for incurable patients “who have outlived themselves”.

A representative democratic government is managed by elected officials and headed by a Prince (from Princeps, “The First”) who does not take decisions without permission. He is chosen for life but can be deposed if he displays tyrannical aspirations. The European craving for precious metals is ridiculed by the fact that these are used in Utopia to make fetters and manacles for the slaves doing the hard and dirty work in Utopia.

The Utopians detest war “as a very brutal thing” and it is only used as a last resort, either to punish the country of a foreign aggressor or to free a friendly nation. Although all citizens, including the women, are trained in warfare, Utopia prefers to use mercenaries – the “worst sort of men” - from a rude and wild nation.

In wars, the priests in Utopia strictly oversee the fighting to minimize enemy casualties. They never lay their enemies’ country waste nor burn their corn. There are several religions, including Christianity, which has been brought there by missionaries. All religions are tolerated provided that they share the beliefs in a Supreme Being, the Creator of the Universe, and the immortality of the soul. In life after death, virtuous people will be rewarded and vicious people will be punished.

Utopian thinking ... and the future

A utopia is something that is far away from us or even impossible to reach. However, there may be elements that might partly still be desirable – for example, a society where everyone has the chance to pursue happiness or where everyone’s basic needs are satisfied. This double meaning is even used by Thomas More himself, who introduced the term. As already mentioned, Utopia means “No Place” in Greek but in English it is pronounced the same way as Eutopia (place of happiness).

It is doubtful whether Thomas More really envisioned the island of Utopia as the ideal society. In some areas, their customs are at odds with his own beliefs. However, it is clear that he gives a critique of many social shortcomings of his time, some of which are still with us today.

A number of experiments in history with an "ideal form of government", strongly imposed and controlled from the top, all ended very badly. The book Utopia also inspired dystopian thinking, e.g. 1984 by George Orwell and Brave New World by Aldous Huxley, where they in fact warn about these kinds of “ideal” societies.

To conclude in the words of More himself about the explorer Hythlodaeus, who claims that he has visited this ideal state: “In the meanwhile, though it must be confessed that he is both a very learned man and a person who has obtained a great knowledge of the world, I cannot perfectly agree to everything he has related. However, there are many things in the commonwealth of Utopia that I rather wish, than hope, to see followed in our governments.”

By Tom Vanderstappen