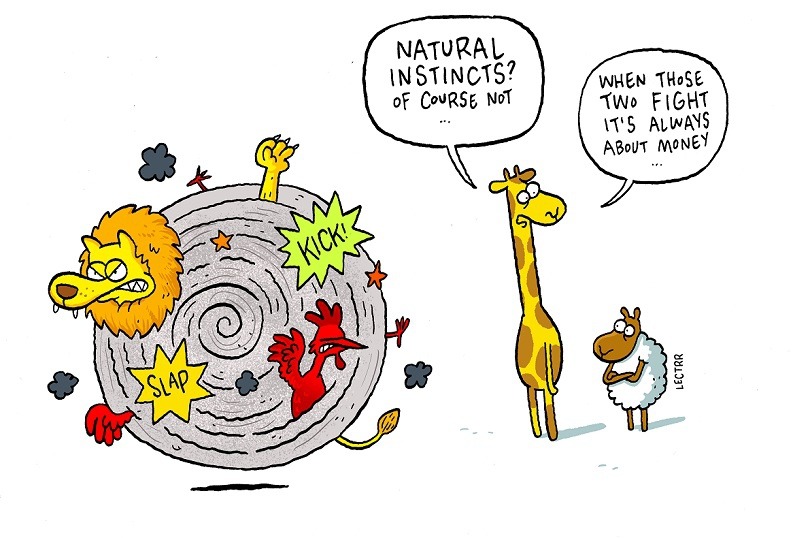

The perpetual tensions pulling at Belgium can be hard to explain to outsiders, but one way do so is by looking at the factor behind so many clashes in history: money. A glance at the economic history of Belgium shows swings between the two halves of the country, Dutch-speaking Flanders in the north and French-speaking Wallonia in the south. It sometimes feels like the moment Flanders finally caught up with Wallonia, more than half a century ago, it also unleashed a political confidence that continues to voice itself. It also carried over a lingering sense of resentment that suggests the Flemish still have a chip on their collective shoulder about the long period when the region and the people were subservient to the French-speakers.

Until 183 years ago, most of what is now Belgium was part of some other entity, whether the County of Brabant, the County of Flanders, the Holy Roman Empire, the Spanish Netherlands or the Austrian Hapsburg Empire. There were none of the rivalries that gnaw at Belgium today. Cities and communities were looser entities, with little of the political identity that currently defines nation states or regions, and most of them were tied to a feudal overlord anyway.

Early trading accounts of the region show how Flanders was at the intersection of routes, from the Netherlands to France, and from Britain to the rest of Europe. By the end of the Middle Ages, Bruges and then Ghent and Antwerp became successors of the city-states of northern Italy as centres of wealth and commerce – even though Flanders was ruled oppressively from outside. In the south, many mediaeval towns emerged, each with their own prince, but none enjoyed the status of the Flemish. Flanders also had its own manufacturing, from spinning and weaving (tapestries were a particular luxury), as well as services like finance.

By the early 19th century the economic and political maps of Europe were being redrawn. The Flemish cities that had thrived in the Middle Ages were now in decline. Flanders was seen as a backward peasant country. But coal and metal were discovered in Wallonia. Entrepreneurs flocked to the region, some from afar, like the Cockerill family from Leeds. Wallonia became an economic powerhouse in Europe during the industrial revolution.

Early trading accounts of the region show how Flanders was at the intersection of routes, from the Netherlands to France, and from Britain to the rest of Europe. By the end of the Middle Ages, Bruges and then Ghent and Antwerp became successors of the city-states of northern Italy as centres of wealth and commerce. Ghent became the most populated city north of the alps after Paris. In Ghent, pictured above, the 91 meter Belfry tower and the towers of the Saint Bavo Cathedral and Saint Nicholas' Church are just a few examples of the skyline of the period, highlighting the status that the city enjoyed at the time.

When Belgium declared independence in 1830, breaking away from the Netherlands, its new ruling political elite was entirely French-speaking. While Dutch was acknowledged in the new Belgian constitution, French de facto remained the only language for education, politics, military, business and religion.

The shift back to Flanders took a long time to play out. Already by the end of the 19th century, Wallonia’s coal industry was losing its edge to others based on gas, electricity and oil, but it took until after the 1950s for the decline to set in. By the 1970s, mines and factories started to close. With nothing to fill the steel and coal gap, unemployment rose.

At the same time, industry in Flanders flourished. Outside investment, mainly from the US, helped the expansion of light industrial and petrochemical industries from the 1960s. The port of Antwerp is now the second largest in Europe, while its entrepreneurship, its education system, and its worker ethos began to pay off.

This is still largely the case. Some 83% of all Belgian exports come from Flanders. Flemish workers are ranked fourth worldwide in terms of productivity. They are also prized for their multilingualism, education, loyalty and productivity. With a population of 6.5 million, Flanders is about twice as big as Wallonia. It provides 58% of the national gross domestic product (GDP), compared to 23% for Wallonia. Eurostat figures show that while per capita GPD in Flanders is 121% of the EU average, in Wallonia it is 86%. The Flemish unemployment rate is 5.0%, in Wallonia it is 10.2%.

Of course, it is worth mentioning Brussels too: it has a role as a Belgian cogwheel, almost above the bickering Flemish and Walloons. But the capital is largely excluded from the economic arguments between the two sides.

Map showing the Walloon and Flanders regions. Dutch is spoken in Flanders (green). French is spoken in Wallonia (red). German in spoken in the eastern parts of the country (blue). Brussels remains a separate region and is officially bilingual. While in the past, Dutch was the language that dominated the streets of Brussels, this has changed today with the majority of Brussels residents speaking French as their first language.

The main political resentments are still between the Flemish and the Walloons - and mostly stem from the economics. Today, many in Wallonia still rely on social security provided by the Belgian federal government. Since it is mainly the Flemish industry and taxpayers who provide government funds, this irks in Flanders. By some calculations, if Wallonia was on its own - without Flanders or Brussels - each of its residents would earn €1,200 less a year from welfare transfers.

Egged on by identity politicians, many in Flanders still see Walloons as work-shy scroungers in a sclerotic rust belt. They contrast Flanders' entrepreneurial, service-led economy to Wallonia's struggle to overcome the collapse of its smokestack industries. There is rhetoric about one-way sponsorship, about Wallonia’s apparent unwillingness to pull itself out of its economic funk. This ties in with the enduring resentment over the subordination of the Flemish culture and language for much of Belgian history.

Wilfried Swenden, a Belgian politics lecturer at the University of Edinburgh says the Walloon decline can be compared to the north of England or Baden Wurtenburg in Germany, regions that have suffered from the decline of the coal industry. “It is not easy to replace these industries when they fail,” he says.

Swenden says the reversal in economic fortunes has fed Flemish separatist sentiment “It feels economic growth hemmed in by a more reactionary, socialist neighbour,” he says. “That at least is the narrative of the Flemish nationalist, who see two economies and democracies living side by side.”

The situation has changed slightly in recent years. Wallonia's economy has moved to revive itself. It is now home to such international giants as Caterpillar, Johnson & Johnson, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and even Microsoft. With tax breaks, it developed business park/research hubs that foster new industries like aerospace and biotechnology. But the region still lags behind Flanders by almost every measure: productivity, exports, income and employment.

Swenden says it is an improvement, but it is not enough. “The gap is not narrowing. So even if Wallonia is growing, the differential is still there,” he says.

By Leo Cendrowicz