Djiboutian president Ismail Omar Guelleh is running for a fifth term in elections scheduled for this Friday, April 9th, but Emmanuel Macron’s government in France appears to have few doubts about the outcome of the election.

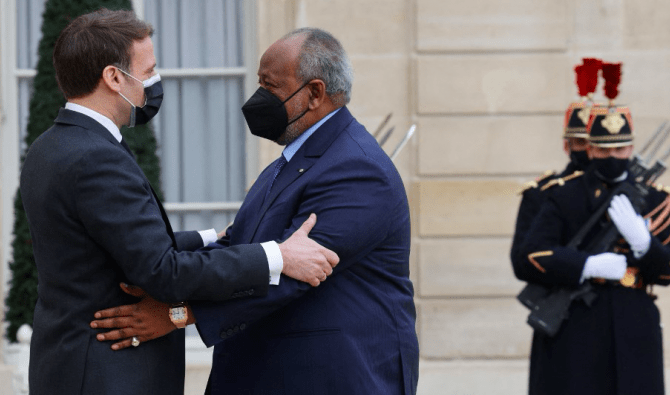

In a high-profile visit to the French capital in February, Macron’s welcome of Guelleh and their talks over the future of France’s military presence in Djibouti played out with hardly a mention of the election. Paris clearly views this election, like all of the others held since Guelleh first took power in 1999, as a fait accompli.

But unfortunately for France, the diplomatic concessions Macron’s government is making to Djibouti don’t appear to make the East African country any more inclined to re-prioritize its relationships with its longtime French allies. Instead, Guelleh’s overriding policy priority over the past several years has been strengthening Djibouti’s relationship with China at the expense of its other partners. In fact, with both China and the United States currently vying for their interests in this small but strategically pivotal corner of the Horn of Africa, France might soon find itself left out entirely.

Great powers at the “Gate of Tears”

Djibouti, a country of less than one million people, has long been seen by global powers as indispensable. It lies on the shores of the Bab-el-Mandeb or “Gate of Tears,” which links the Gulf of Aden to the Red Sea and separates Africa from the Arabian Peninsula. Around 20% of the world’s trade passes through this 18-mile-wide passage, and as the recent blockage of the Suez Canal demonstrates, even minor disruptions along the Red Sea shipping route have an outsized impact on global commerce.

Djibouti’s importance is further enhanced by its military value. The country finds itself surrounded by countries in crisis, including Yemen but also Eritrea, Somalia, and Ethiopia. This chronic instability has allowed Ismaïl Omar Guelleh to obtain a lucrative series of contracts from foreign militaries looking for bases in the region.

France, which numbered the country among its colonial possessions until 1977, has traditionally been Djibouti’s closest ally, but after decades of privileged relations with its former colonial overlord, the African nation began looking elsewhere. In 2002, the United States established its only permanent African military base in the country, later joined by troop contingents from France as well as Italy, Spain, Germany, and Japan. More recently, however, one country – China – has enjoyed pride of place, progressively leaving both France and the US in the cold.

Buttering up a dictator?

In an attempt to revive the Franco-Djiboutian special relationship, France has intensified its charm offensive, with Guelleh’s visit to Paris coming just under two years since Macron made his own official visit to Djibouti. In addition to diplomacy and pageantry, the French are going to great lengths to ignore Guelleh’s human rights record and the harsh political repression that has kept him in power for over two decades.

France’s willingness to overlook the democratic deficit of its former colony was readily apparent during the Guelleh visit, with Macron making little mention of his counterpart’s dictatorial tendencies or of his rewriting Djibouti’s constitution to remove term limits for presidents. Indeed, at the time of the trip, it appeared that Guelleh would be running unopposed, after Djibouti’s heavily suppressed opposition groups declared their intent to boycott the race and decried the tendency of successive French presidents to “butter up” strongmen like Guelleh.

Despite not commenting publicly on the upcoming election, the French government has made one important gesture towards the pretense of democracy in Djibouti: after Guelleh’s visit, the French government processed a request from little-known opposition candidate Zakaria Ismaïl Farah to renounce his French nationality, allowing Mr. Farah to run in Djibouti and saving Guelleh from the prospect of a one-horse race.

Geopolitical wrangling

If Macron is serious about re-establishing French relevance in Djibouti, however, he will have to contend with Djibouti’s current status as a flashpoint of the fierce rivalry between China and the United States, and as the only country in the world to host both American and Chinese military bases. Beijing currently seems to hold the upper hand in this contest, thanks to its expansive investments in the country.

In 2009, China overtook the US as Djibouti’s largest trading partner, and the gap has only grown since then. Djibouti is part of the PRC’s Belt and Road Initiative, and has benefitted from Chinese-backed infrastructure projects such as a railway connection to Ethiopia. Chinese firms have also taken over management of key pieces of infrastructure in Djibouti, such as the Doraleh container terminal.

Doraleh, in fact, offers one of the most tangible examples of how other international partners have been sidelined in favor of Chinese interests in Djibouti. After Guelleh’s government summarily seized the facility from then-operator DP World in 2018, the company took Djibouti to the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA) and won multiple arbitration decisions along with hundreds of millions of dollars in damages. Djibouti’s response has been to ignore those rulings entirely, instead handing over control of Doraleh to state-backed China Merchants Ports Holdings.

Some American military leaders fear their own interests in Djibouti could go the same way. China’s military base in the country is located just a 15 minute drive from Camp Lemonnier, from which US and European military and intelligence personnel operate, and Beijing’s profligate spending has led personnel at US Africa Command (AFRICOM) to admit “we have concerns we are being out-competed.” With Guelleh’s government heavily indebted to China, US planners are wary of a scenario in which China could come to control Djibouti’s all-important port outright – which would leave American operations in the region at the mercy of Beijing.

Were such a turn of events come to pass, French, American, and other Western officials would have little to show for their willingness to ignore their partner’s mockery of both democratic governance and international legal institutions, other than perhaps a case study in the shortcomings of realpolitik.