As befitting a numbers man, Belgium’s Finance Minister Vincent Van Peteghem is clear, precise, and, yes, measured. Mostly.

We’re sitting in his swanky, second-floor offices at 11 Rue des Colonies (Koloniënstraat), near the swish new BNP Paribas Fortis headquarters and less glamorous surroundings of Gare Centrale (his other office in town is next door to the Prime Minister’s official Lambermont residence in Rue de la Loi).

Van Peteghem’s spokesperson joins us in a spotless meeting room, Zaal Warande, handing him a lengthy briefing entitled ‘Brussels Times interview’.

He flicks through the top corner of each page with his thumb and forefinger as if he’s counting bank notes, but then barely glances at the meticulously prepared file. As a former spokes, I feel a pang of empathy.

Van Peteghem, two metres tall, lean, bespectacled and smartly dressed in a crisp white shirt, cuts an imposing figure. He has arrived a little late for our meeting, but, apologising, manages to cover a lot of ground in the next 40 minutes.

We start by discussing what the 43-year-old former business school professor sees as his main achievements – and biggest disappointment – since taking up the reins as Finance Minister and Deputy Prime Minister in October 2020, representing the centrist Christian Democratic and Flemish party (Christen-Democratisch en Vlaams, CD&V).

“What was important and what we focused on a lot was bringing tax, fiscal and finance issues back to the people,” he says. “In the past, ministers always used to avoid saying much about tax and everything around it. I think we needed to make these policies as concrete as possible and several of our measures had a huge impact.”

€22 billion hit

He immediately lists three examples, starting with the “Van Peteghem bond”. Launched last September, thanks to a reduced withholding tax it provided an attractive 2.8% net interest rate compared with the stingy amounts then on offer from Belgium’s high-street banks. It was a massive hit with the public.

“We raised €22 billion. The last time that there was such a successful launch was in 2011 when €5.9 billion was raised, so it was quite an achievement. People were looking for better returns on their savings and what is definitely clear is that the banks then understood that they had to fight for their customers. It was good for the country.”

The second initiative Van Peteghem highlights is what he terms the “most green measure taken by governments in the last 10 years” – the greening of company cars so beloved by Belgians.

“We said in 2021 that we would only give tax advantages for company cars that were CO2 neutral by 2026. It gave a clear signal to the markets, to the constructors and the leasing companies. And today, you can clearly see that we were able to make the shift towards electric cars.”

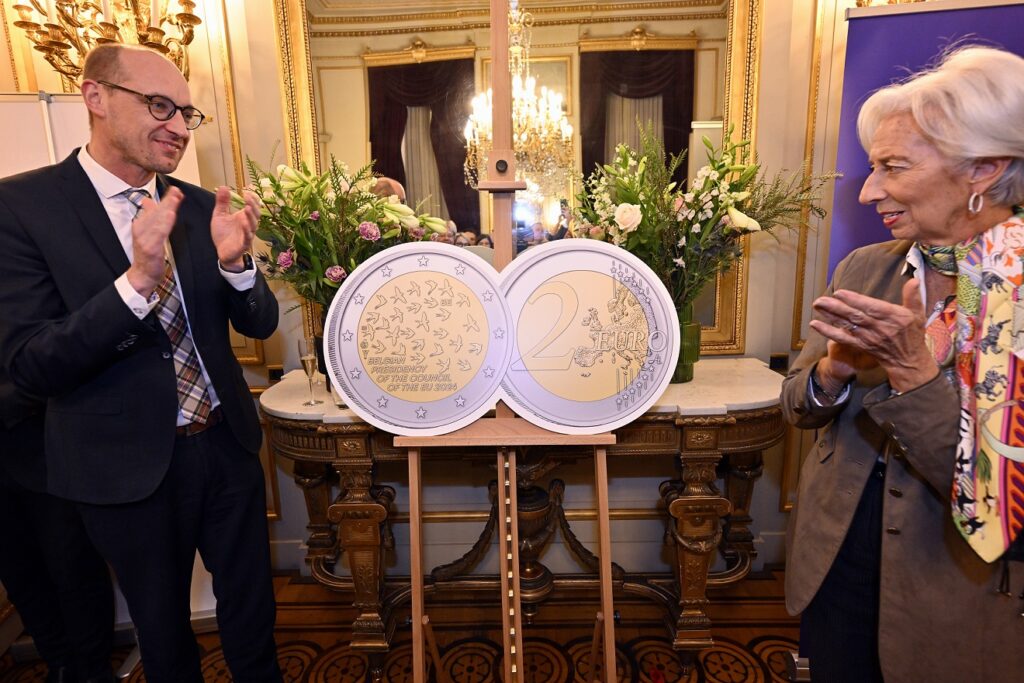

With European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde during the presentation of a special coin to mark the Belgian Presidency of the Council of the European Union and the 25th anniversary of the Euro currency

The third success he flags is the so-called ‘pillar two’ measures to force multinationals to pay a minimum 15% tax on their profits.

“We were able to create a level playing field with smaller firms who had the feeling that, while they paid their taxes, the multinationals were free riders. We’ve been able to implement these measures at OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development], European and national level.”

Tax setback

And his biggest disappointment?

Van Peteghem cannot conceal the frustration he still feels after his bold tax reform blueprint – dubbed “visionary” by the Flemish media – was torpedoed by rival parties in the governing coalition.

“We are the world champion for taxes on labour, so we looked at how to reduce the burden on employers, while at the same time making the tax system more simple, just and fair for individuals.”

Whether people are single, married or cohabitating should not influence how much they pay, unless they have children or dependents, he explains.

It sounds reasonable, so why was the policy axed?

Van Peteghem and Prime Minister Alexander De Croo during a plenary session

“It was indeed very reasonable,” he declares. “The problem was that people around the table looked too much to lobby groups behind them. If you do politics, you should do it for everybody. Some parties forgot that during the negotiations. I had the feeling that they lacked leadership and a little bit of courage to make a huge step forward.”

Who does he blame most?

After a moment of hesitation, he points to Mouvement Réformateur (MR), the French-speaking liberals led by George Louis Bouchez. “Everybody had concerns or remarks but the liberals were the most difficult,” he concedes. “During the election campaign we’ve seen all the parties saying we need a huge tax reform. If we’d decided this a couple of months ago, people would already have more net income compared with now.”

Election risks

Since he has raised the subject of the general election, I ask if he fears victory for Vlaams Belang will harm Belgium’s image abroad. At the time of writing, polls were predicting that the far-right party was on course to claim the largest number of seats in the Chamber of Representatives, ahead of the conservative, nationalist New Flemish Alliance (Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie, N-VA) and Parti Socialiste.

“I'm quite sure that Vlaams Belang will damage our reputation and I'm not happy about that,” he says.

Van Peteghem draws a parallel with the Netherlands where the far-right Freedom Party (Partij voor de Vrijheid) led by Geert Wilders finished first last November.

“The impact isn’t immediate. But when I talk with colleagues at the G20 [the Group of 20, a forum for major economies] or Ecofin [the EU’s Economic and Finance Ministers], you hear that it’s definitely having an influence on the position of the Netherlands in multilateral organisations.”

Politicians in Belgium need to confront why the far-right is becoming more popular, he says.

“We need to listen to what people are saying, what they are worried about and what’s keeping them awake at night. These are not illogical issues. It's about their money. Will I still have enough at the end of the month? Is my neighbourhood safe? If I get sick, will I get appropriate care? These are the things that people are thinking about and they need to feel that we have respect for their concerns.”

Some voices in the N-VA suggest the party should cooperate with Vlaams Belang. Could Van Peteghem see that happening with the CD&V?

“No.” He doesn’t elaborate.

Time to change the subject.

NATO frustration

Belgium’s paltry spending on defence has unsurprisingly created more than a degree of frustration at NATO HQ – and with a certain US Presidential candidate – especially given the volatile, all-too-threatening environment on the EU’s borders. The alliance expects its members to earmark at least 2% of national GDP on defence. Last year, it estimated Belgium would spend only 1.13% in 2023, the second lowest among its members (Luxembourg pays just 0.72%).

Why does Belgium contribute so little?

Van Peteghem for once looks uncomfortable.

“We are looking to the future and we have agreed with NATO that we need to accelerate the work that has to be done. But, for me, the main important discussion is how to better organise our European defence. We have different weapons in every army in different countries. We need to streamline that, to coordinate more and better. Defence should be a focus for the next European Commission.”

Van Peteghem is the current chair of the board of governors of the European Investment Bank and is pressing its President, Nadia Calviño, to prioritise defence and security – but admits that the EIB already has its work cut out supporting the green transition, digital growth and competitiveness.

“The challenges are big but if we're not able to be more efficient at European level, even if we spend three or four percent of GDP on defence, it will not be enough.”

Colossal debt

Van Peteghem is keen to put the onus on the EU, but Belgium must surely shoulder some share of responsibility, I suggest.

The country’s level of debt is colossal. The EU’s budget rules state that the maximum debt ratio in member states may not exceed 60%, but the European Commission forecasts that Belgium’s public debt rises will be 105.0% of GDP this year rising to 106.6% of GDP in 2025 (with its budget deficit rising to 4.4% by this year and 4.7% by the end of 2025).

Belgium’s public debt rises is expected to rise to 106.6% of GDP in 2025

Asked why, Van Peteghem gives a matter-of-fact response. “You will have a high debt ratio so long as you're not able to balance your revenues and expenses,” he says.

“The budget and debt is always an indication of how your welfare state is organised,” he continues. “In Belgium, we have a very good social security system. If you study, you don't have to pay for that for the rest of your life. If you get sick, there are accessible and nearby hospitals and healthcare.

“But our budget for pensions and healthcare will increase by 25% in the next five years due to the ageing of our population. That’s why I’m much in favour of the European economic governance framework, the ‘Ghent guidelines’ as we call them, recently approved by the European Parliament.”

The new rules, brokered by Van Peteghem in February, give countries such as Belgium more time to trim their deficits, while also exempting any contributions they make to EU projects from their national accounts. A win-win for all, apparently. It sounds like a fudge, as always.

If figures aren’t your thing, look away now.

Under the deal, Belgium commits to reducing its current deficit of 4.4% of gross domestic product to 3% over the next seven years. In cash terms, this means reducing its €26 billion deficit by around €3.4 billion per year through cuts and savings.

Reform and rethink

“This gives us the opportunity to make reforms necessary to bring the budget and deficit under control,” Van Peteghem says. “To maintain our welfare state, we need to reform our healthcare system and rethink our tax system. We need to rethink our pension and labour market system. That's the focus we need to have in the next government. Not just to cut social security, but to defend and build upon the [welfare] system that we are well known for all around the world.”

Speaking at the Chamber at the Federal Parliament in Brussels

He certainly has the patter off to a tee, leaving me nearly, but not completely, spellbound.

So how come the Nordic states also offer generous welfare provisions without piling up enormous debts?

“One of the main differences is that their tax and labour markets are organised much better. Their employment levels are much higher too.” The target is to get 80% of Belgium’s working age population in a job. “We're almost there in Flanders, but in Wallonia or in Brussels the level is much lower. If we were able to reach an 80% employment level in the whole country that would have a positive impact on our revenues and expenses because less people would be getting unemployment benefit.”

Tackling fraud

We briefly touch on two of Van Peteghem’s other main areas of responsibility: the fight against fraud and drug traffickers.

He sees better collaboration between government departments and agencies as crucial in both fields.

While acknowledging that, by its nature, it is “very difficult” to assess how big a problem fraud is in Belgium, he says his coalition partners backed a “very ambitious” approach.

He outlines three action plans, focused on collaboration between different services at the federal level, more coherent policy and better compliance. His services also looked at improving collaboration between the justice department, the administration and the police. “In the past, when an administrative investigation was complete it would be passed to justice who would then re-open the whole investigation. There was a kind of Chinese wall between the departments and now we have opened that a little bit. Of course, everything still has to be done correctly, in line with the law. We’ve also tightened legislation,” he says.

While Van Peteghem is unable to put a figure on how much extra tax these changes will bring in, he insists that they have resulted in closing loopholes and making it that much harder for people to evade their liabilities.

War on drugs

Last year Belgian customs seized a record 116 tonnes of cocaine in the port of Antwerp, as well as five tonnes in Zeebrugge, which suggests that the improvements spearheaded by Van Peteghem are bearing fruit. Again, a more efficient, joined-up approach between the police, customs and courts is at the heart of his action plan. He highlights his “very good cooperation” with Aukje De Vries, the Dutch State Secretary for Finance, and source countries in South America such as Colombia, Ecuador and Panama.

“It's only by making each piece in the chain as strong as possible that we can have a huge impact in the fight against drug traffickers. We have invested a lot in extra scanners to check containers entering Antwerp port that are seen as high-risk because they’re coming from South America or we’ve had problems with the companies involved in the past.”

The scanners are very effective, he says, spotting even small quantities of packages hidden in containers. “Will we ever win the war on drugs? That will also depend on the people who use drugs. If there is demand, there will always be supply. People who use drugs need to take into account that they have blood on their hands, as well as up their noses.”

Mayor and father

Vincent Van Peteghem is not short of ‘hats’.

As Finance Minister and Deputy Prime Minister, his responsibilities include hosting meetings with his member state counterparts during Belgium’s six-month presidency of the EU and chairing the European Investment Bank’s board of governors. First elected to the Chamber of Representatives in 2014, he later became Mayor of De Pinte in East Flanders. He is also husband to Evelyn De Blieck and father to three daughters under the age of ten, Josephine, Florine and Olivia.

That’s a lot of roles to juggle. How does he do it?

“For my children, it’s about finding the time and, if you're available, making sure that they have a good, qualitative time with you. Of course, having a good wife helps too,” he says, banking a few brownie points. “It's not so extraordinary, though. A lot of young families struggle today. In our case, it's maybe a little bit more, a little bigger.”

As for his professional roles?

“I know what my vision is and where we're heading to. I only put things on the table that I completely believe in. And that really helps me defend everything I’m doing in the government.

“Minister of Finance is a huge job. When you start, you're not always aware of that. There are always big decisions to make. Then you go up to Europe and discussions on the Capital Markets Union or the digital euro. At the local level it could be about where the bank ATM [cash machine] has gone.

“It's a huge package of responsibilities but I have a fantastic group that supports me and an administration that helps a lot. That’s the only way you can manage.”

He actually has three teams of personal staff: the Finance Minister’s cabinet in Rue de la Roi, the office of Deputy Prime Minister in the unfortunately named Rue des Colonies, and support in his home base of De Pinte.

So is Van Peteghem ever tempted to quit politics and return to his old job as a professor at EDHEC (École des Hautes Etudes Commerciales du Nord) Business School in Lille?

He laughs.

“I was always interested and active in politics at the local and later national level,” he says. “Now I have the opportunity to make an impact. I didn’t have any doubts about standing as a candidate. If you’ve been in an academic career you also need to teach. As a politician, I still like to explain everything I do!”