Simon Gronowski was just 11 years old in April 1943 when his mother pushed him out of a cattle car that was headed for the Auschwitz death camp. That was the last time he saw her: she stayed on the train.

Gronowski, who turned 90 last October, slows down as he tells his tale of wartime survival. “She said in Yiddish, ‘Der tsug geht tsu schnell’ – ‘The train is going too fast.’ And those were her final words to me,” he says.

Gronowski recounts a gripping yet gruelling story. He was bound for the gas chambers, like millions of victims of Nazi atrocities. Yet he was one of the few, very few, who escaped to tell the tale. Decades on, it still needs telling.

Born in Brussels in 1931, Gronowski still lives in the city. His house is just 500m from the Gestapo’s former headquarters during the Nazi occupation of Belgium, at Avenue Louise 453. “My story is a miracle,” he says. Indeed, it has been turned into an opera, while the three Belgian resistance fighters who helped him escape are being commemorated with a memorial.

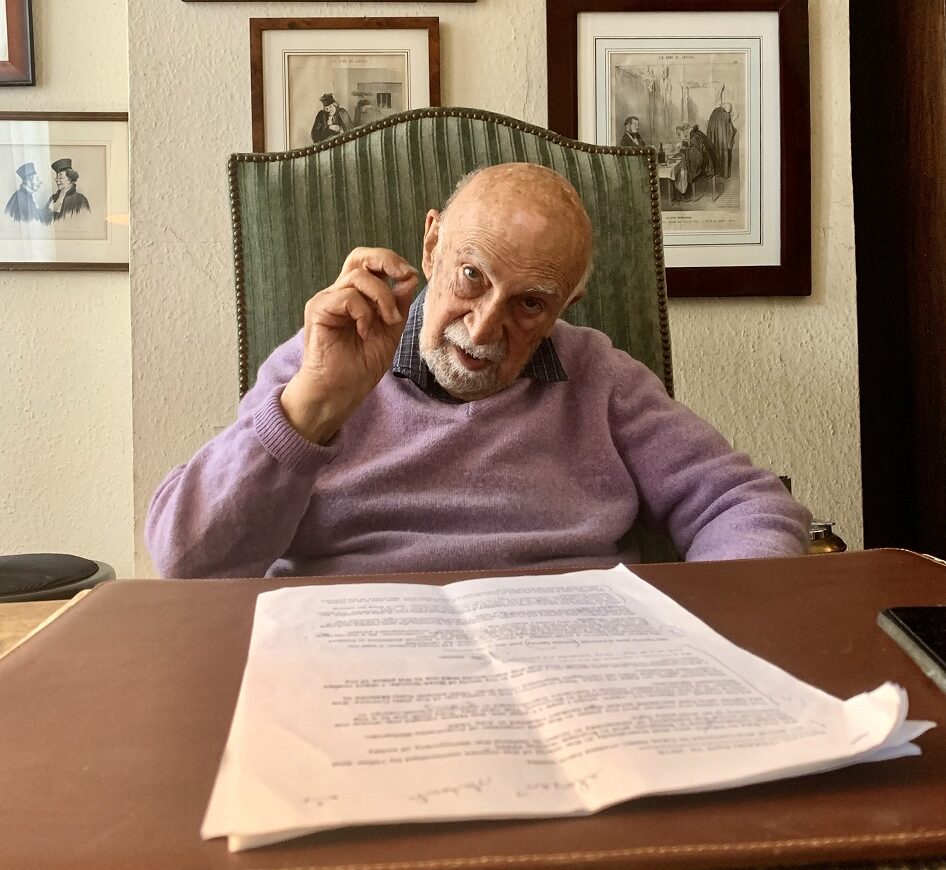

Speaking in his study, surrounded by memorabilia from his long career as a lawyer, the genial Gronowski explains how his father Leib (later westernised to Leon) was born in a shtetl, a small village in Poland. His mother, Chana (westernised to Anna), was from Lithuania. After a wave of antisemitic hostility in eastern Europe, both left their homes for Belgium.

His father initially worked in the coal mines near Binche, but after he caught silicosis, he started a leather goods business in Brussels, which was soon successful enough for him to buy his own house. By the time war broke out, the family was happily settled in Brussels, with both the young Simon and his older sister Ita excelling at school.

Simon and his parents in Brussels

In 1940, the German army marched through Belgium and occupied the country, en route to invading France. By September 1942, the first ‘razzias’ or raids against the Jews took place in Brussels, and the family went into hiding in Woluwé-Saint-Lambert.

Gestapo at breakfast

But on March 17, 1943, the Gestapo came knocking at their door when he was having breakfast with his mother. They were taken to the basement of the Gestapo’s Avenue Louise headquarter, and the next evening to the Kazerne Dossin detention camp in Mechelen. “I was given the number 1234, and my mother got the number 1233. Those were our deportation numbers,” he says.

They were held at the Kazerne Dossin for a month before the Belgian Waffen SS bundled them onto Convoy 20. This was a train carrying some 1,631 Jewish men, women and children in 34 cramped wagons, around 50 in each.

“I didn’t understand anything,” Gronowski says. “I was still in my world of boy scouts. I didn’t realise I had been condemned to death and the train would lead me to my place of execution.” This was just one of the convoys that would send 28,000 Jews from Belgium directly to the death camps. But shortly out of Mechelen, around Boortmeerbeek, it stopped. “I heard shouting and shooting,” Gronowski says.

The train had been halted by three daring young Belgian resistance fighters, Youra Livchitz, Jean Franklemon and Robert Maistriau, using a red paper and a lantern to halt the train. They then tried to free the prisoners, helping 233 to escape, of which 118 survived.

Livschitz was later captured and executed, Franklemon was sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp but was liberated in May 1945, and Maistriau was arrested in March 1944 and liberated from Bergen-Belsen camp at the end of the war. Last year, Brussels authorities agreed to erect a monument to the raiders, while three city streets will be named after them.

No-one could open the doors on Gronowski’s car, though. His own escape only came later when the train was moving again. He had fallen asleep in his mother’s arms, but she woke him up: the sliding doors were now open and a couple of people had already jumped from the train. “The cattle car was a gaping black hole, but light came through a small opening,” he says.

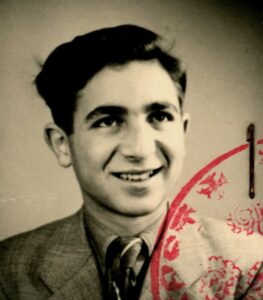

Simon and his mother

Holding his shirt, his mother told him to jump. Simon demurred, so she pushed him out. Yet she didn’t follow, and the guards soon turned up to close the sliding doors. “My first instinct was to try to rejoin my mother – but then unconsciously, like a reflex, I turned and ran,” he says. She died in the gas chambers three days later. “If she had told me to stay with her, I would have stayed and died with her. If I had known she would not jump, I would not have jumped.”

Lost boy

Gronowski was still some 80km from Brussels when he tumbled out of the train. His mother had given him a 100 franc note on the train, which he had slipped into his sock, but he was still in a precarious situation. “I walked through all night, through the woods,” he says. “I had no fear. I hummed ‘In The Mood’ by Glenn Miller to encourage myself.”

But the following morning, he sought shelter. At the village, Berlingen near Borgloon he approached a small house (he knew to avoid big houses, which were often occupied by Nazis). “I rang the bell and told them that I was lost after playing nearby, and needed to get home,” he says. “But they immediately wondered what a muddy little French-speaking boy was doing in Flanders, on the other side of the country from Brussels.”

The mother who answered the door took him to a neighbour who took him on his bike to county constable Jean Aerts, a soldier with a gun. “I was terrified they would take me back to the Nazis,” he says. “He didn’t believe me about playing and getting lost – he went to the train station and told me in French: ‘I know everything. You were on that train. Don’t be afraid, I am a good Belgian. We won’t betray you.’ He took me to the station in Ordingen. I took the train to Schaerbeek and was back home in the evening.”

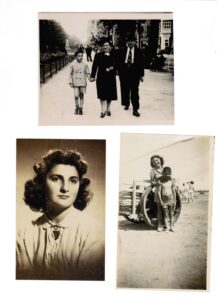

He eventually reunited with his father, who had only escaped from the Gestapo raids as he was in hospital at the time. They spent the rest of the war hiding with local families. As for his sister, Ita, she had already been caught in 1943: as she had Belgian nationality, she had initially been spared deportation, but the Nazis later changed the rules, and she died in Auschwitz, aged 19.

Simon with his parents and sister Ita

Simon and his father survived to see Belgium liberated, hiding with friends. But his father was a broken man: he had held out hope that his wife and daughter would return, but they didn’t. He died in despair in July 1945, leaving the 13-year-old Simon an orphan.

Hidden trauma

In the decades after, Gronowski kept the childhood trauma to himself. “I felt guilty. Why are they dead, and I am alive?” he says. “I would cry a lot when I was alone.” He studied and became a doctor in law at 23 – he is still a lawyer today. He married Marie-Claire Huybrechs, had two daughters, Katia and Isabelle, and is a grandfather to four. He also became an accomplished jazz pianist. But he assumed people were not interested in his story.

For six decades, few would hear him talk of the past. But 20 years ago, his story seeped out. A publisher asked him to write a memoir, which he did, entitling it, ‘L’Enfant du XXe Convoi’ (‘The Child of the 20th Convoy’).

His story struck a chord. Even though his experience was unfathomable, it was inspiring. He was invited to share his tale at schools and memorial events. His memoir was recounted in a children’s picture book, ‘Simon, le petit évadé’. “It hurt to talk about it again,” he says. “But I also felt I was bringing something positive, especially to young people. And that makes me happy.”

Eight years ago, Gronowski was introduced to the British composer Howard Moody, who was so touched by the story that he wrote an opera about it. Called ‘Push’ after his mother’s gesture on the train, the opera was staged last year, at Boortmeerbeek, where the convoy was stopped. It has already been performed at La Monnaie Opera for King Philippe and Queen Mathilde, the English opera festival in Glyndebourne, at Chichester Cathedral, and in the House of Lords.

In 2012, he was called up after one of his events at a Belgian school. It was a sculptor, Koenraad Tinel: he was the same age as Gronowski, yet his father and brother had been enthusiastic Belgian Nazis. Indeed, Tinel’s older brother, Walter, was an SS guard at the Kazerne Dossin. Wracked with guilt about his Nazi family, he reached out to Gronowski, and they met at the offices of the Belgian Union of Progressive Jews (UPJB).

They became firm friends, co-writing a book, ‘Finally, Liberated,’ and giving lectures together. In 2020, they received honorary doctorates at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) and Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB). “Koenraad is more than a friend, he is a brother,” Gronowski says. And before he died, Tinel’s brother, Walter, asked to see Gronowski to plead for forgiveness. “I took him in my arms, and I forgave him. And I’m happy I did,” Gronowski says. “I never hate. I don’t want to bring a message of sadness but of hope.”

Hope

Gronowski is still active, and inspiring hope. In the first weeks of lockdown after the coronavirus pandemic struck in 2020, he began giving impromptu piano recitals to neighbours: shifting his electric piano to beneath a windowsill and flung the window open, to tap out a jazz tune. And this March, he played the piano at a ceremony by Ixelles commune awarding honorary citizenship to Andrée Geulen-Herscovici, now 100 years old, who saved Jewish children at the Gatti de Gamont School in Woluve-Saint-Pierre by hiding from a Gestapo raid.

Gronowski still advocates for causes, including refugees and undocumented people. “We have to welcome these people with humanity and dignity,” he says.

And he still talks to young people. “As a victim of criminal hate, I have never had hatred,” he says. “I believe in human good. Belgium is a beautiful country. A country of freedom, of peace, tolerance and democracy. Keep our country that way so our children never have to face the barbarity I did.”