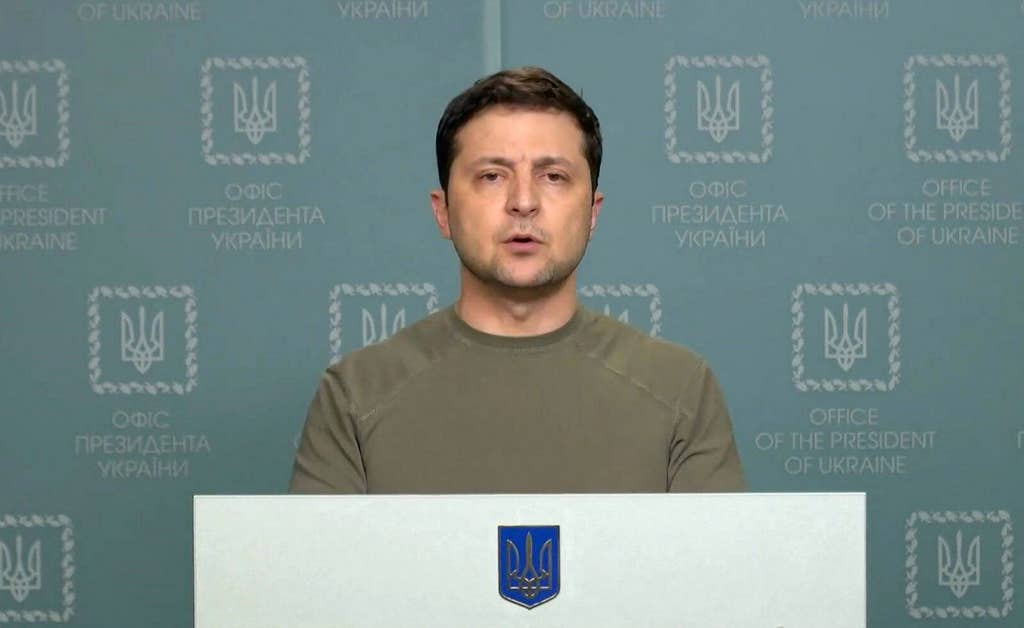

An interview last week in The Washington Post with President Volodomyr Zelensky has sparked criticism against him for not warning in time about the risk of war with Russia.

According to the interview by Liz Sly, the comments he made to the American newspaper justifying his “failure” to share with Ukrainians details of US warnings that Russia planned to invade Ukraine has triggered a cascade of public criticism unprecedented since the war began.

As previously reported, Zelensky was quoted as saying in the interview that his fear that Ukrainians would panic, flee the country and trigger economic collapse was the reason why he chose not to share the warnings passed on by U.S. officials regarding Russia’s plans.

In fact, the American warnings were well-known to the public and Zelensky did his utmost to warn his people and the outside world about the danger and to appeal for help and support. Most often his warnings fell on deaf ears or were not taken seriously by the outside world, including the EU.

No-one could foresee that Russia, in case of an invasion, would violate international humanitarian law and commit acts which may account to war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The outside world and those Western leaders who met Putin were also fooled by Russia. In mid-January 2022, Russian president Putin announced a partial troop withdrawal from the border with Ukraine as a possible sign that he wanted to climb down from the tree but he continued to keep his cards close to his chest.

The build-up of Russian military force at the border with Ukraine, threatening to invade the country, took place in full view. The outside world was powerless to prevent an invasion which seemed next to inevitable besides issuing statements and threatening Russia with unprecedented sanctions that did not frighten the Russian president.

A time line, based on the reporting in The Brussels Times, shows the inactivity of the EU in the weeks before the Russian military build-up. The last European Council meeting before Christmas 2021 ended without any concrete decisions. Decisions about sanctions against Russia were taken after its invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 and only incrementally in packages.

The US started to evacuate staff from its embassy in Kyiv towards the end of January 2022 and this could have indicated intelligence about a Russian invasion into Ukraine but still there was no feeling of an immediate attack.

EU’s foreign policy chief Josep Borrell said after a foreign affairs council meeting in Brussels with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken that the EU did not think that there was a need to take any kind of precautionary measure from the point of view of the number of staff and their presence in Ukraine. He also cautioned against the risk of an immediate attack.

The prevalent feeling in Brussels was to wait and see and not do anything which could provoke Russia to invade Ukraine. After the war erupted, it would take time for the EU, the EU member states and the US to decide on delivery of weapons to Ukraine, as if they first wanted to see if Ukraine had the will to defend itself and the ability to inflict losses on the Russian troops.

A crucial event in the prelude to war were the replies by the US and NATO to the Russian demands for security guarantees, including a withdrawal of NATO forces from Eastern Europe and assurances that Ukraine will never join NATO. The content in the replies, about a month before the invasion, have not been disclosed but reportedly the US and NATO rejected the Russian demands.

As regards the possibility of Ukraine joining NATO in the future, the US, the EU and NATO were all of the opinion that it was Ukraine’s sovereign decision to take. By then, the Ukrainian government had already started to reconsider its position about NATO membership and to focus on EU membership.

NATO’s expansion to the eastern European countries that during the cold war belonged to the Soviet sphere of influence has always been controversial. For Russia, the deployment of NATO troops in these countries is seen as security threat and under Putin’s regime it has also become part of a historical narrative linked to restoring Russia’s glory as a world power.

Ukraine was vaguely promised NATO membership at a NATO summit in Bucharest in 2008 but the actual implementation has been kept on hold since then and some NATO members regret the promise. An amendment in Ukraine’s constitution states NATO membership as an ultimate goal of the country but statements by the government before the outbreak of the war indicated that it no longer was a major strategic concern.

More important for Ukraine is to develop its ties with the EU and join the Union in the future after meeting the conditions as long as its independence and territorial integrity are guaranteed. Closer economic and cultural ties with Western Europe would also reconnect Ukraine with its historical past when it was an independent kingdom (‘Kyivan Rus’) until the onslaught of the Mongols.

It is impossible to know if a clear no to Ukraine ever joining NATO would have satisfied Russia but at least it would have deprived Kremlin of a pretext for invading a peaceful neighbor which did not pose any military threat to it. Ukraine had been disarmed of nuclear weapons after the dissolution of Soviet Union in return for security assurances by the US, UK and Russia (Budapest Memorandum in 1994).

It is worth to recall that Ukraine’s president attended the Munich Security Conference on 19 February just before the Russian invasion. At the conference, he appealed passionately for support to Ukraine. The current military threat against Ukraine is a threat against the whole security framework in Europe after WWII, he warned.

In an interview by journalist Christiane Amanpour, president Zelensky explained why he had remained so calm despite warnings about imminent war. “Any provocation is dangerous and we need to stay calm. I trust more our own intelligence.”

How can you live in a country if you say that war will erupt any day? he asked rhetorically. What will then happen to the economy? “We aren’t prepared to put ourselves in ‘coffins’ waiting for an invasion.”

“We don’t need sanctions after the war has started, then it’s too late,” he said in the interview. “If Russia would withdraw its 150,000 strong troops around our borders, there will be no need for sanctions.”

The interview in The Washington Post ends with a quote from an ordinary Ukrainian, Oksana, 30:

“My biggest question is about the level of atrocities we saw, and I think about whether they could have been prevented,” she said. “It will damage us to discuss this now. Ukraine is winning because of our belief in the president and our armed forces. So I’m ready to wait for the explanation until after we win the war.”

She was referring to atrocities perpetrated by Russia and for which Russia bears the full responsibility.

A recent report by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe's Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR) included initial findings and recommendations connected to violations of laws which may account to war crimes and crimes against humanity, mainly by Russia and to a much more limited extent by Ukraine.

The list of reported violations by Russia is long and includes indiscriminate attacks against civilian targets (such as Mariupol Drama theatre, the railway station in Kramatorsk, hospitals and schools), brutal sieges of cities as a method of warfare, and the use of weapons with wide area effects in densely populated areas (cluster munitions).

The report does not end by this and reports about sexual violence against women, extrajudicial executions of civilians, unlawful treatment of prisoners of war, suppression of peaceful protests in occupied cities, obstacles to the delivery of humanitarian assistance, and forced deportations of civilians to Russia or the so-called People’s Republics in Donbas.

Kremlin wants to restore the power of former Tsar-Russia and Soviet Union, against the international order and under the false pretext of “de-nazifying” Ukraine. Alleging that Zelensky did not do enough to prevent the war or making him a “scapegoat” for the humanitarian disaster in the country plays into the hands of Russia and acquits if from responsibility for its unprovoked and illegal attack.

M. Apelblat

The Brussels Times