As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine rumbles towards a year of open hostilities with an uncertain stalemate on the front, a second 'front' to the conflict rages largely unseen by the general public: cyberwarfare.

Unlike the armed confrontations happening on the ground in Ukraine, the West is directly involved in the cyber war, fending off targeted attacks against companies and government institutions by Russian state actors, as well as its proxies.

This is evidenced by a recent distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack carried out by the pro-Russia hacktivist group KILLNET against the website of the European Parliament (EP) after it declared Russia as a state sponsor of terrorism.

The group is suspected to have ties to Russian government-linked organisations such as the Federal Security Service (FSB) and the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR). KILLNET and other groups have launched numerous cyberattacks against Western companies, media, government services, and critical infrastructure since the start of Russia's war in Ukraine.

“That (EP attack) was definitely tied to one of the pro-Russian groups that, previously at least, did not have direct ties with the nation itself. There is an interest in those threat actors being part of the – I almost hate saying the word– cyber war game that’s going on. It’s a mix, a hybrid, between strictly nation-state actors… and supporting groups,” said Jesper Olsen, Chief Security Officer at Palo Alto Networks.

Olsen, a former cybersecurity specialist with NATO and the Danish Army, notes that the threat landscape is radically altering as a result of the Ukraine war, with an increasing profit motive to support Russia’s cyberattacks against Europe.

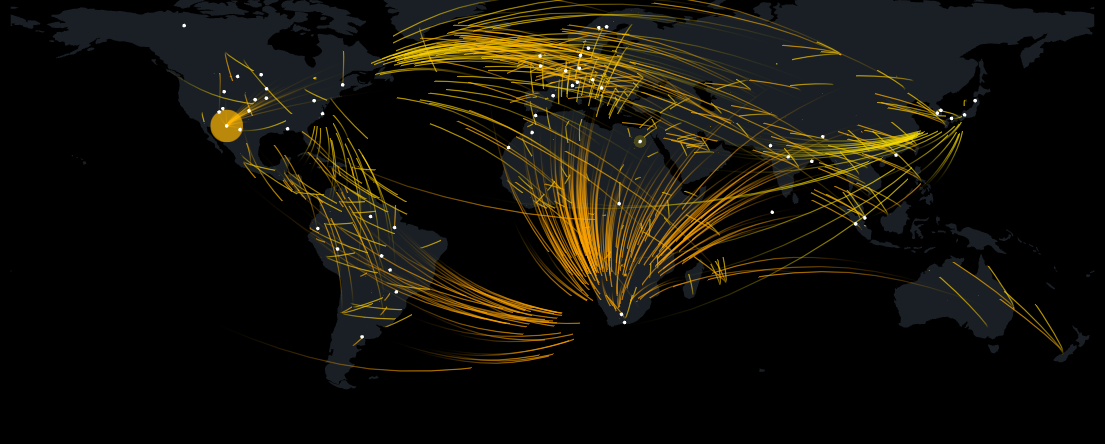

Credit: Netscout

“There seems to be an interest from a financial perspective to support Russia from the threat actor side of things. Those that are already pro-Russian, they would like to engage more with (Russia) and support them in terms of this conflict,” he added.

Indeed, there appears to be a perfect storm of factors encouraging a wave of Russian-backed, or inspired, attacks against Europe and critical infrastructure. Rising energy prices, the declining value of cryptocurrencies, and increased backing of Russian state actors mean that nuisance attacks, such as ransomware attacks, are increasingly attractive for Russian cyber criminals.

“The economy also impacts threat actors… They’re more aggressive when the economy tanks,” Olsen explained. As the war between West and East intensifies, there are fears that attacks may become more intricate and tailor-made, especially against critical infrastructure.

Advanced capabilities

When desired, Russian threat actors have the capability to deploy intricate and devastating attacks. In 2007, following the Estonian government’s removal of the Bronze Soldier of Tallin Soviet-era war monument, Russia conducted the second largest state-sponsored cyberattack in history, crippling the entire Estonian banking sector, government services, and media outlets.

For now, Olsen says, Europe has not yet seen a greater onslaught of intricate attacks against critical infrastructure. He credits this in an increase in cyber maturity and the profit incentive behind most attacks.

“Threat actors are mostly going after the money. Money is the biggest motivator for them. If there is no money in it, then they don’t really have the interest in going in. They do a business analysis before they risk exposing themselves. The biggest pay-out right now is still private organisations,” Olsen said.

Evidence of Russian state-backed actors deploying more intricate attacks are also surfacing. One suspected FSB-backed actor, labelled by Palo Alto as Trident Ursa (or Gamaredon), launched an unsuccessful tailored attack against an unnamed petroleum refining company within a NATO Member State.

Live map of cyberattacks and threat actors across the globe. Credit: Kaspersky

Vulnerable private companies still remain the bread and butter for Russian cyberattacks. While European governments have greatly invested in state-level cybersecurity, the growing Internet of Things (IoT) and attacks against companies show how the European private sector is considerably vulnerable for nuisance attacks.

“This ties into critical infrastructure, because they rely a lot on different types of IoT, like in health care. Until two or three years ago, not many organisations thought about cybersecurity in the context of any connected device in a hospital.” This is evidenced by recent attacks against medical groups in Belgium.

Russian-speaking ransomware group Lockbit caused havoc in the Belgian province of Luxembourg. The group accessed the systems of the Vivalia medical group, demanding a ransom and threatening to publish 400 gigabytes of patient data, including employee data, diagnoses, and other sensitive data.

As a result of the attack, hundreds of planned procedures were cancelled and consultations could not take place. Following the cyberattack, Vivalia posted "massive losses."

The newly introduced NIS2 and CER EU cybersecurity directives aim to force the private sector to engage in proper cybersecurity practices, shifting away from voluntary commitments, especially for companies that form part of Europe’s critical infrastructure.

Private companies which deal in “essential” and “important” sectors must now implement technical, operational, and organisational measures to manage risks and cyber threats and to minimise the impact of attacks. This includes incident handling, business continuity, proper encryption, reporting, and training. Nation states have 21 months to implement the new rules.

“A closer collaboration between the public and private sector is essential for success. Threat actors might have an advantage in terms that they don’t care about the industry… They move laterally across industry vectors. We should be as agile in approach in terms of sharing knowledge and learning from each other,” the Palo Alto expert said.

Second front of the Ukraine war

While Russian threat actors rely on nuisance attacks in western Europe, in Ukraine, attacks are increasingly aggressive.

In a comment to The Brussels Times, Ukraine’s government agency responsible for communications and cyber defence, the State Special Communications Service of Ukraine (SSSCIP), said that Ukraine had endured some of the largest scale Russian attacks in its history in the run up to Russia’s full-fledged invasion.

“The war in cyberspace began almost a month and a half before the kinetic war,” a spokesperson said. “A heavy cyberattack on the information systems of numerous public institutions, which defaced some of them, was waged on 14 January last year. We believe that this date is the start of the full-scale war against our State in cyberspace.”

In the first three days of Russia’s failed offensive on Kyiv, cyberattacks on Ukraine’s government and military sector surged by 196%, according to data from Check Point Research. Phishing emails in East Slavic languages increased seven-fold. Last year, cyberattacks against Ukraine tripled, the SSSCIP reveals.

“The largest DDoS attack in the history of our country took place on 15 February. It lasted several months and had varying intensity. There was also an attack on public and banking institutions the day before the invasion, on attack on Viasat satellites, which were used as backup communication channels of the Ukrainian military,” the agency spokesperson said.

Related News

- KLM and Air France loyalty program hacked in cyberattack

- Antwerp cyberattack costs city €1.2 million in parking fines

- Half of Belgian companies fall victim to ‘successful’ cyberattacks

On the night of the invasion, Ukraine neutralised attempted cyberattacks against Ukraine’s largest telecommunications operator, Ukrtelecom, as well as against one of Ukraine’s regional electricity providers. The communications service says that this attack was “the most technically complex and well-prepared” one of the war.

These Russian attacks, part of its hybrid war against Ukraine, demonstrate the importance of collective cybersecurity in Europe, as well as the technical capabilities of Russian state and state-sponsored threat agents. “If it had succeeded, according to different estimates, up to two million Ukrainians and thousands of businesses, institutions, and social facilities could have suffered a blackout,” they said.