Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie and Nina Simone are jazz legends, but in the 1960s, they were unwittingly used as decoys by the United States to deflect attention from its role in its meddling in African countries like Congo, which had just won its independence from Belgium. This extraordinary story is told in a new documentary, 'Soundtrack to a Coup d'Etat', which juxtaposes jazz with political murder.

Directed by Johan Grimonprez, it cut deep into the blood-and-rubber ties between Belgium and Congo, shining a light on the United Nations, jazz as a political agent and the plot to assassinate Congo’s first democratically elected Prime Minister. It is a spiderweb of geopolitical intrigues playing like the jazziest history lesson imaginable. With a heavy dose of irony, it presents the theatre of world politics of the 1960s as a grand spectacle – complete with flashy title cards and theatrical trumpets. But its plot is deadly serious.

Patrice Lumumba, who helped lead Congo’s struggle from a Belgian colony into an independent republic and became its first Prime Minister, was wildly popular – not just in Congo but in the entire African continent. However, the Pan-African movement that Lumumba personified was viewed with alarm by Western countries, worried about threat to their resources across the continent. He was quietly targeted for assassination.

Just two months after Congo’s independence, Lumumba was dismissed as prime minister and placed under house arrest. He briefly managed to flee but was captured again in December 1960. By this time, army colonel Mobutu Sese Seko had seized control of the country in a coup.

Mobutu would then order Lumumba to be sent to the breakaway province of Katanga. Belgian secretly arranged his transfer, he was flown by Belgian national carrier Sabena, and Belgian officers tortured Lumumba when he landed in Katanga. Just five hours after his arrival, he and two of his collaborators were brought to an open spot in the savanna and executed by firing squad.

“Looking at the murder, there is a connection to jazz, but also a connection to decolonisation,” says Grimonprez, who directed the 2009 Alfred Hitchcock fantasy ‘Double Take’ and the 2017 investigation into corruption in the defence industry, ‘Shadow World’.

Grimonprez is clear: Belgium was not just complicit in Lumumba’s murder but was one of its principal perpetrators. “Everyone thinks murder as a weapon is typically CIA, but Belgium can do it just as well. Even if the gun was provided by the CIA, Belgium pulled the trigger,” he says. “It is not only the assassination of a democratically elected head of government, it is also the destabilisation of a country and the reversal of a dynamic on a continent.”

Year of Africa

Fresh from its independence from Belgium’s colonial rule in June 1960, Congo entered the United Nations in September, together with 15 other newly independent African countries. To the annoyance of many Western countries, this tipped the balance of voting power in the UN General Assembly to the newly expanded Afro-Asian bloc.

It was the height of the Cold War at the time and the Soviet Union took advantage of the situation, with leader Nikita Khrushchev inviting all the heads of state to discuss “demilitarisation and decolonisation” at the UN General Assembly in New York.

“Of course, this was the moment right after many African countries gained independence and had just become part of the UN. They called it the Year of Africa,” Grimonprez says. “That was a political earthquake because together, they could gain the majority vote, which freaked out the West, and mainly the United States.”

Parade in post-independence Congo

Seeing this as an opportunity, Khrushchev proposed what would become the UN Declaration on Decolonisation (Resolution 1514), calling for the rapid independence of the remaining colonies. The segregationist policies in the US and the global interest in the civil rights movement also seemed to vindicate the Soviet accusations of US hypocrisy.

The Resolution was adopted in December 1960 – while Lumumba was imprisoned – with 89 countries voting in favour. And while no nations voted against it, nine abstained, including the US, the UK and Belgium.

Grimonprez, born in Roeselare in 1962, just two years later, says decolonisation triggered a flood of CIA interventions in Africa. “That moment in time is actually the ground zero of the West for the neocolonial grab of the resources in the African continent. It is a ‘scramble for Africa’ again, because of its resources,” he says

L’Empire du silence

Grimonprez’s documentary is the result of digging into Belgium’s metaphorical backyard and confronting the heart of darkness he found. “I grew up in Belgium, but in school, I never learned about our own shadows,” he says. “Congo was labelled L'empire du silence.”

The shadows were in the heart of Africa, but Belgians did not have to deal with it. “Whatever news came back from Congo was completely hushed up and vice versa. The Belgian Congo was kept as a bubble and the people were kept ignorant, both in Belgium and in Congo,” he says.

He makes the comparison with the US civil rights struggles. “In the US, the articulation about ‘othering’ is so prevalent because the other is inside. Americans are seemingly better able to speak about it because the confrontation was within their own country,” he says. “But the confrontation in Belgium was always the empire of silence.”

The economic exploitation of Congo was also hidden from Belgians, including Grimonprez. “I never learned about any of it. Brussels is built almost entirely on rubber money via King Leopold II. The layout of the streets and the avenues in Brussels is completely shaped by rubber money. The city is a colonial print of imperialism, but it is not named as such. And that, the not naming of things, I think is embedded in Belgium's history as a whole.”

Grimonprez describes it as a trauma and argues it still defines the country. “Belgium is younger than the United States, so if the United States is behaving like a teenager, then Belgium is behaving like a toddler,” he says.

Jazz as a political tool

The movie’s historical context is provided through archival footage from speeches by the likes of human rights activist Malcolm X and then-US President Dwight Eisenhower. The sober account plays to a rhythm as the Eisenhower administration, in a bid to restore its image, turned to an unconventional weapon: jazz.

“Jazz was another device for the United States to spread propaganda. They sent black jazz ambassadors across Asia and Africa to win the hearts and minds of sort of the global south,” Grimonprez says. For example, Louis Armstrong, one of the most influential figures in jazz, was dispatched to the Congo as a diversion from the unfolding CIA-backed coup against Lumumba.

Louis Armstrong performing with locals

More and more jazz ambassadors – including Nina Simone, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie and Melba Liston – were sent out to newly independent countries to perform alongside covert CIA operations. But that led to internal struggles. “The flip side to this is, as Dizzy says in the film, that the musicians did not go out there to justify racial segregation inside the US,” Grimonprez says. “The African American population was not yet allowed to vote at the time. This was all happening while the civil rights movement in the States was at its height, and people were still lynched occasionally. And that is also why Nikita Khrushchev shouted and banged his shoe in the General Assembly: because of the Congo crisis.”

While these musicians were sent out as propaganda instruments, they were not passive, Grimonprez says: they still had their own voice. “Louis Armstrong is sent out and used, but he remains very critical of US policy. When he was on his Africa tour, he refused to play for a segregated, all-white audience in South Africa.”

Armstrong arrived in Congo when Lumumba was under house arrest. “Armstrong was still in Africa when Lumumba was killed in January, and he was furious when he learned he was used as a smoke screen. He even threatened to resign or give up his US citizenship,” Grimonprez says.

Solos and sidesteps

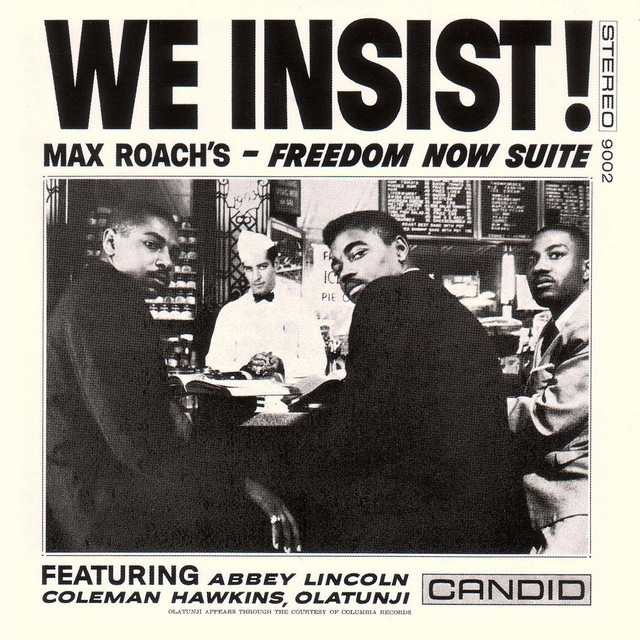

If anything, the film shows that jazz can be a political agent – not only for the neocolonial powers but also for the civil rights movements. “Musicians like Abbey Lincoln and Max Roach, who were both a part of that civil rights movement, used music as a political tool as well,” Grimonprez says.

This is illustrated elegantly in sequences that bookend the documentary. It opens with Eisenhower’s call for Lumumba’s death to the rhythm of Max Roach’s famed drums and closes with the announcement that Lumumba has been liquidated and Abbey Lincoln’s seconds-long scream on their joint album 'We insist! Freedom Now'.

Max Roach’s record protesting US intervention

“This album was famously all about civil rights, and a lot of African American scholars have written about this moment as the opening salvo of the black militant movement,” Grimonprez says. “And later, it was Abbey Lincoln and Max Roach who initiated the protest in which they crashed the Security Council when they announced that Lumumba was killed. So it only felt right to end the film with that.”

'Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat' swings and shakes like the jazz that underscores the story. The speeches, testimonials and archival footage all play to the rhythm of the music and musicians featured in the film. Sometimes Grimonprez sets up a prolonged solo that might feel jarring until the puzzle pieces suddenly fall together. At other times, quick cuts build in a crescendo of information, trumpets and horns to lead to a climax of realisation and insight.

Whether it's uranium for nuclear weapons or cobalt for smartphones and electric car batteries, Grimonprez cleverly intersperses decades-old statements about the effects of mining on the locals’ health and grand UN speeches about self-determination with short and shiny modern-day advertisements for iPhones and Tesla cars.

While the current situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo (or DRC, as it is now known) is only briefly mentioned, the parallels are clear; the players might be different, but history is repeating itself. “It’s all connected,” he says. “Now, it is about different minerals as it was then. But it is the same region, and above all, the same template. Colonies can become independent, but apparently not too much – especially not as long as we depend on them for expensive materials.”

Ceci n’est pas un coup d’état

Almost seven million people have been displaced as a result of conflicts across the DRC, and just a few months ago, the UN Security Council voted to withdraw the 15,000 peacekeepers stationed in the country.

A substantial chunk of ‘Soundtrack to a Coup d’État’ is dedicated to Western hypocrisy: the film asserts that Belgian and American interests in the Congo had more to do with the trillions of untapped mineral resources in the country.

Setting the figures of Denis Mukwege (the Congolese gynaecologist who received the Nobel Peace Prize for his research on sexual violence) against those of mineral extraction paints an even starker picture: 80,000 women raped since 1999 recorded in his hospital, against $24 trillion in mining turnover. “On a map, you can link those cases directly to the villages where mining takes place nearby. Rape and murder are used to drive people out,” Grimonprez says.

Much of the documentary’s narrative is shaped around the archives: Grimonprez relies on audio memoirs, narrated excerpts of political novels, performance videos and, of course, jazz music.

Particular attention was paid to the footage of the UN General Assembly, and striking excerpts were set aside. “Videos of someone picking his nose, falling asleep, looking at his watch: I was able to link footage of a pipe-smoking Allen Dulles, the head of the CIA at the time, with his denial of a coup to Belgian surrealism artist Magritte: Ceci n’est pas un coup d’état,” Grimonprez says.

The film chronicles a tragic chapter in history, but Grimonprez remains hopeful that it can help the healing process. “We will show the film in Kinshasa and the Brussels Matongé district. I am curious how it will be received there, but I am sure of one thing: whatever happens, there will be dancing,” he says.

This article was first published in Spring 2024.