As the battle of Brussels mayors comes to a close, Sunday's local elections saw a progressive pushback in the Belgian capital against June’s right-wing surge, with socialist parties forming a "red wall" which held back MR’s predicted "blue wave".

On Sunday, Belgian residents went to the polls to elect their local mayors and municipal councils. In the capital, 19 municipalities were up for grabs, with many foreseeing French-speaking liberal party Mouvement Reformateur (MR) building on their success in June’s elections, after they stole the Socialist Party (PS)'s crown as the biggest party in Brussels.

In many ways, Sunday’s results still confirmed certain trends seen back in June in the Belgian capital: a strong centre-right performance which saw MR-led lists coming first in the Brussels municipalities of Watermael-Boitsfort and Forest (at the expense of Ecolo), with a strong performance from Les Engagés across the board.

MR came second in Schaerbeek, and is now in a tug-of-war with PS to take the mayorship. In Ixelles, a backroom deal with PS will see them enter in the ruling coalition, while in the City of Brussels, Mayor Philippe Close held on but opted to go into a ruling coalition with the liberals, attracting vociferous criticism from the left.

A polling station in Brussels, Sunday 13 October 2024. Credit: Belga / Hatim Kaghat

Yet overall, MR’s assault on the capital did not take any significant scalps from the Socialist Party’s traditional bastions.

"The right-wing trend that has swept over Wallonia has not affected Brussels in the same way," political expert at the Centre for Socio-Political Research and Information (CRISP), Caroline Sägesser told the Brussels Times.

"If you look at Brussels from a global point of view, and at the score of the PS, PTB, Team Fouad Ahidar and the Greens together, you see that this is a region that's mainly left-wing. And it remains so," the expert stated.

Socialist strongholds

After June's disappointing results, the socialists bounced back on Sunday to hold onto inner city fortresses like Saint-Gilles, Anderlecht and Molenbeek-Saint-Jean (just) – all places where people thought they could lose their mayorships. But in Brussels on Sunday, PS were helped by strong local figureheads like Philippe Close and Ahmed Laaouej, who all enjoy high levels of popularity.

Another reason why PS held onto its inner city strongholds was that the expected growth in support for the Belgian Workers Party (PTB-PVDA) was not felt as strongly in Brussels.

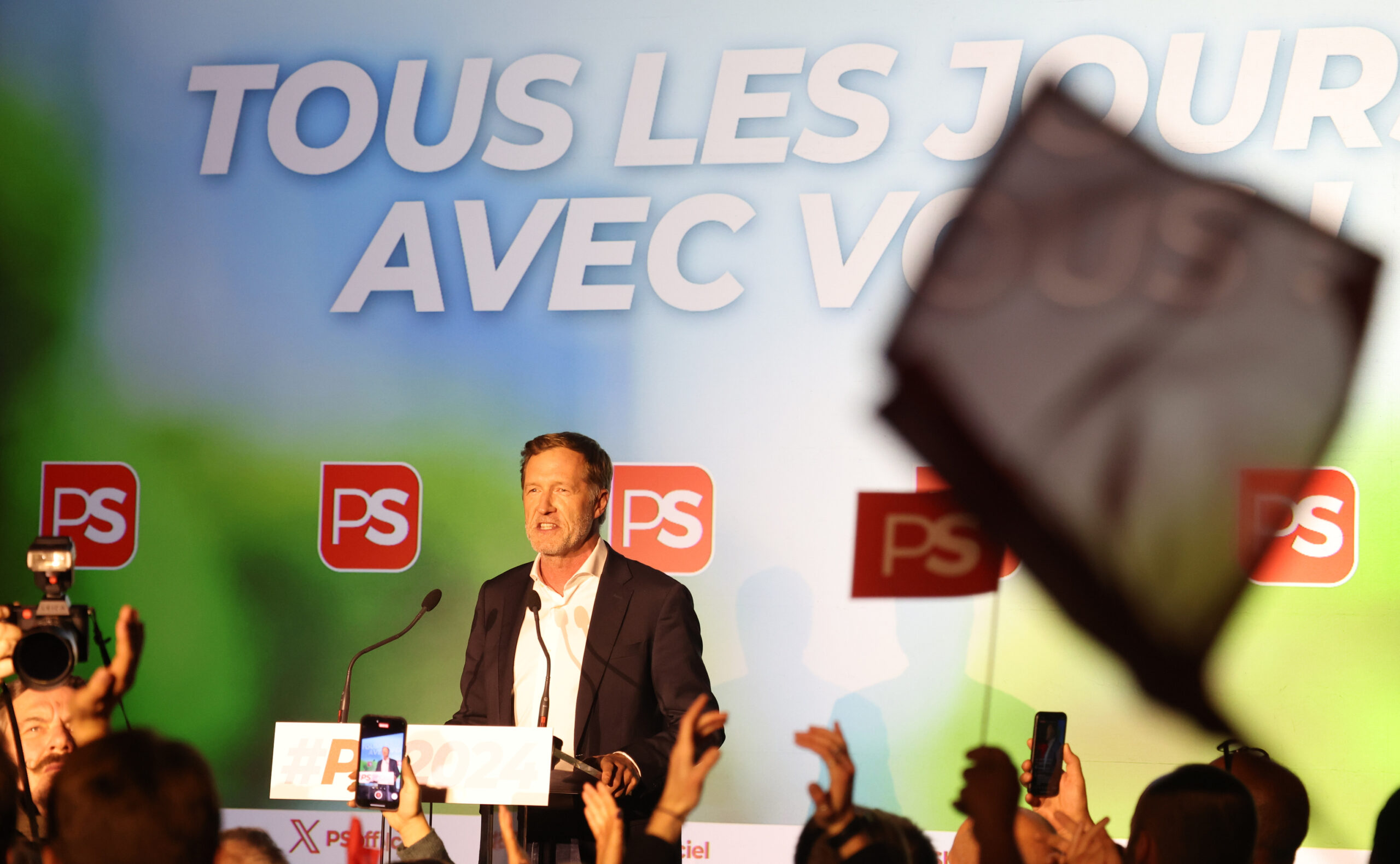

PS leader Paul Magnette delivers a speech at a meeting of the Charleroi branch of French-speaking socialist party PS, on the evening of the local elections on Sunday 13 October 2024. Credit: Belga / Virginie Lefour

The radical left party had topped the polls in Brussels back in February, and in June’s federal results came first in five Brussels municipalities. Yet Sunday saw both significant gains but also slightly disappointing results overall, like in the City of Brussels.

According to Sägesser, one reason for this was the second electoral success of Team Fouad Ahidar, which on Sunday came mainly at the expense of PTB's vote share. Ahidar was a former member of Vooruit who broke off from the Flemish socialists over their immigration policies.

"Whenever Fouad Ahidar is present, PTB has really scored badly when compared to June’s results. And where there is no list of Fouad Ahidar, PTB's score is comparable to that of June." Six months ago, most would not have believed that a new political party in Brussels, coming from the Muslim community, will score well in nearly every municipality it presents itself, Sägesser remarked.

PTB were also overlooked for a ruling coalition by Saint-Gilles Mayor Jean Spinette (PS), who chose to return to rule with Ecolo (where they had a previous agreement) despite the Belgian Workers Party coming second.

Belgian Workers Party (PTB-PVDA) leader Raoul Hedebouw delivers a speech at a meeting of the Brussels branch of Belgian radical left party on Sunday 13 October 2024. Credit: Belga / Hatim Kaghat

"Until now, the socialists have been extremely reluctant to go into power with PTB." This is partly down to any social progress made by a PS-PTB coalition would be claimed by the latter, therefore damaging PS long-term.

In Molenbeek, where they posed the most serious challenge for a mayor's office by coming second, an unlikely PS-PTB coalition is set to still go ahead. This would make it the first time PTB have entered into power in Brussels (and second in Belgium as a whole).

However, they would still need the support of a third party for a majority, and importantly, the Belgian Workers Party are entering a "very difficult commune to manage".

"The social problems are enormous, the environmental problems, the debts as well. And of course, if PS goes in coalition with PTB, the regional government to be formed between MR and Les Engagés won't be very kind to them either. They won’t look at Molenbeek with a lot of favour, so they won't receive any additional gifts from the next regional government."

Indeed, the challenges PTB faces in Molenbeek could also impact the party’s future chances in the Belgian capital if the coalition does not work well. "It's complicated for them, I imagine that they are now reaching the conclusion that they probably don't have much potential to grow in Brussels unless they show that they can actually deliver."

Blue waves, red walls

Despite an overall positive trend, MR’s self-proclaimed "blue wave" in Brussels proved to be more of a slight change in the tide.

MR promised to be the answer to the Belgian capital’s security problems by promising law and order coupled with a populist opposition to environmentalism. However, this proved to not be as effective as it was back in June: "They are certainly regaining ground, but I wouldn't really talk of a wave," Sägesser said.

"Security and mobility were probably the two main issues in Brussels, and in the end, focussing on security hasn't brought a very significantly high gain for MR. So maybe for a large amount of the population, this is still not the most important factor in Brussels."

Sägesser added that the lack of a far-right presence in Brussels is also a testament to security being more of a concern for people who live outside of Brussels.

Military and civilian parade on the Belgian National Day, in Brussels, Sunday 21 July 2024. Credit: Belga / Nicolas Maeterlinck

"It's puzzling that for a very huge international city, with the same drugs and security problems that any other major city can have, there is no far right party that can actually get a result in Brussels,” Sägesser said. Furthermore, Sunday has shown that the average Brussels resident is more concerned with issues like housing, mobility or cleanliness.

Indeed, MR fell short on attaining any big municipal targets in these elections – providing it does not gain Schaerbeek, which hangs in the balance. Yet MR’s problems in winning power in the centre of the Belgian capital are wide-ranging.

"The demography is not favourable for them. So I think MR’s future in Brussels will be increasingly difficult in the long run because the population is shifting. We're going to see more and more mayors of foreign origin."

In areas with high levels of multiculturalism, MR could struggle to make a breakthrough despite "trying to open up to having more candidates from foreign origin or people from the Muslim community and so on, but it hasn't worked so well so far."

Good Move is dead

One of the most salient topics of the local election – mobility and the fight against traffic-induced pollution in the Belgian capital – was also one of the most hotly-contested battlefields in Brussels politics.

On Sunday, the future of the controversial Good Move policy was also at stake. Once again, with pioneers Ecolo having taken another beating at the ballot box on Sunday, the future of Good Move could well and truly be dead - but in name only, Sägesser believes.

Good Move is the mobility policy of the Brussels-Capital Region to reduce traffic flows and pollution. Credit: Belga

"I think you have to distinguish between the packaging and the content. Good Move has collected so much negative feedback by now that for sure, it has to be changed," the political expert pointed out. "They have to come with something new, but they won't change the facts."

On this, Sägesser explains that the election results do not change that Brussels needs to increase investment in public transport, reduce the number of cars going into the city and improve the quality of the air – which also is part of Belgium's international obligations.

"It will be called differently. It will be implemented with more care and hopefully better coordination, both with the cities and with the population. But still, they will have to go on in the same direction more or less."

Moreover, the reaction to Good Move was very different from one neighbourhood to another.

In Schaerbeek, where the protests were as strong as in places like Anderlecht, the greens roughly maintained their share of the vote. In Saint-Gilles, the ruling municipal coalition craftily re-dubbed the policy ‘Cool Move’, may have helped the greens to a better result.

"During this campaign, everyone talked about Good Move a lot but I'm not sure that the large majority of the Brussels population rejected it, actually," Sägesser stressed.

Business as usual in Brussels?

As the dust settles from Sunday’s elections, do the results mean business as usual for local politics in Brussels? Sägesser thinks so. The fact that the city is split in 19 different administrations will always ensure that the most important political parties are in power – at least in some of those.

Yet the problems for Brussels in the next six years will be "huge", notably on budget issues, as the region is nearly bankrupt and not helped by huge expenses like the construction of the new Metro 3.

The next Federal Government is also expected to drain public spending in order to balance the budget and reduce Belgium’s public debt, with unions already saying the plans are the "biggest assault on workers’ rights" since 1945. This will undoubtedly have an effect on the management of Brussels.

"Unless the Federal Government decides to significantly refinance Brussels to have more money flowing from the federal to the regional level, it will be extremely difficult because if not, the Brussels Government won't be able to help the municipalities which really need money," Sägesser concluded.