The sea level is rising at a rate that equals the very worst-case scenario of climate scientists, according to a study by the university of Leeds in England and the Danish Meteorological Institute, published this week.

Since the 1990s, the sea level has risen by 1.8cm, as a result of the melting of ice-caps in Greenland and Antarctica. And if current trends continue – and there is no reason to suppose they will not – then the sea level could have risen by 17cm by the year 2100, compared to the most pessimistic forecasts made in 2014 by Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

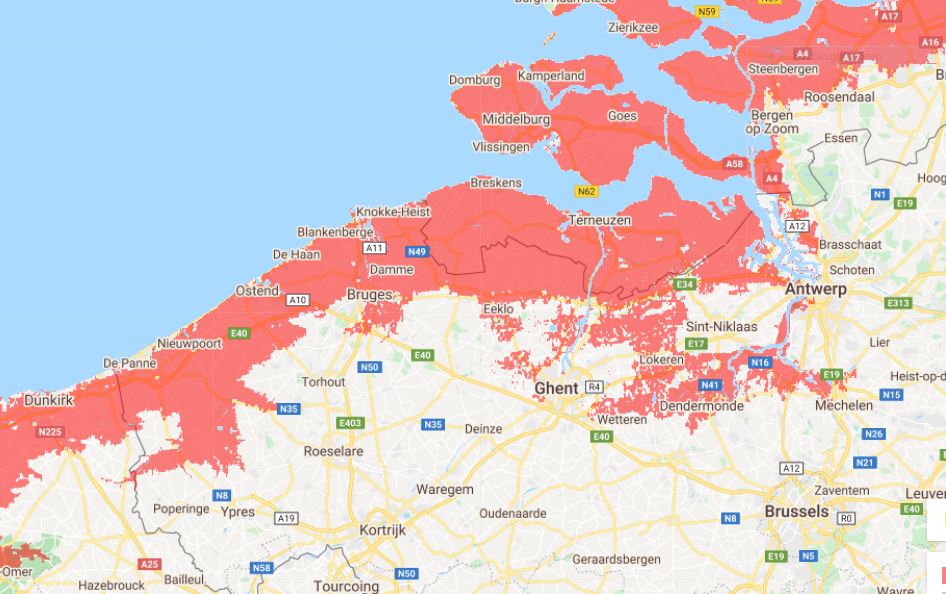

That may not seem like much, but from Belgium’s point of view it could be catastrophic, as much of the country lies at or below the current sea level. According to a simulator from the website coastal.climatecentral.org, by 2030 the rising sea level will present an increased flooding risk all along the Belgian coast and as far inland as Bruges and Eeklo, Dendermonde and Mechelen, and the outskirts of Ghent.

The path of the flooding follows the river Scheldt all the way from the estuary in the Dutch province of Zeeland to Antwerp and farther inland. A decade later the flood plain has extended further, and by the end of the century Antwerp itself has been reached, and the waters are lapping at the foot of the nuclear power station in Doel.

“Although we anticipated the ice sheets would lose increasing amounts of ice in response to the warming of the oceans and atmosphere, the rate at which they are melting has accelerated faster than we could have imagined,” said Dr Tom Slater of Leeds university’s Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling.

“The melting is overtaking the climate models we use to guide us, and we are in danger of being unprepared for the risks posed by sea level rise.”

“You could conclude from this study that even here the most pessimistic predictions could become reality,” Professor Patrick Willems of the university of Leuven told the VRT.

“For Belgium, we would expect the worst-case scenario to be a rise in the sea level by 2100 of 80cm to one metre. Locally, this could deviate significantly from the global average. On the coast of Ostend, for example, the sea level has already risen about 6cm since the 1990s.”

“Because it is a very slow process, most people are not so concerned about it,” said Professor Patrick Meire of Antwerp university.

“Nevertheless, a large part of Flanders is only a few metres above sea level. That means that entire areas of the country are also threatened by a rising sea level. Don’t forget that the North Sea flows far inland via the Scheldt. The tides of the sea can be felt as far inland as Ghent,” he said.

Since 2011, the Flemish government has been implementing measures to protect the coast and other vulnerable areas from the so-called 1,000-year storm. Prof Willems explained, “That is a very heavy storm that coincides with the spring tide and that in theory only occurs once every 1,000 years,” he said.

“Such a storm surge could flood large parts of Flanders. But the higher the sea level rises, the more effort we have to make to prevent a storm surge from occurring more often than once every 1,000 years.”

Alan Hope

The Brussels Times