The story of looted art during WWII is brought back to life in the exhibition “Stolen Jewish Legacies: The Fate of the Andriesse Collection” at the Holocaust Museum (Kazerne Dossin) in Mechelen.

As previously reported, the dramatic story of the looting and partial recovery of a valuable Belgian art and textile collection was presented last November at the Jewish Museum in Brussels but only for one day because of the museum’s closure for renovations. The exhibition is now back on view on the fourth floor of the museum in Mechelen until the end of February.

The exhibition traces the lives and cultural impact of the Belgian-Jewish philanthropists and art collectors Hugo Daniel Andriesse (1867-1942) and his wife Elisabeth Andriesse (1871-1963). It is the first exhibition of its kind in Belgium about the Nazi looting of cultural property.

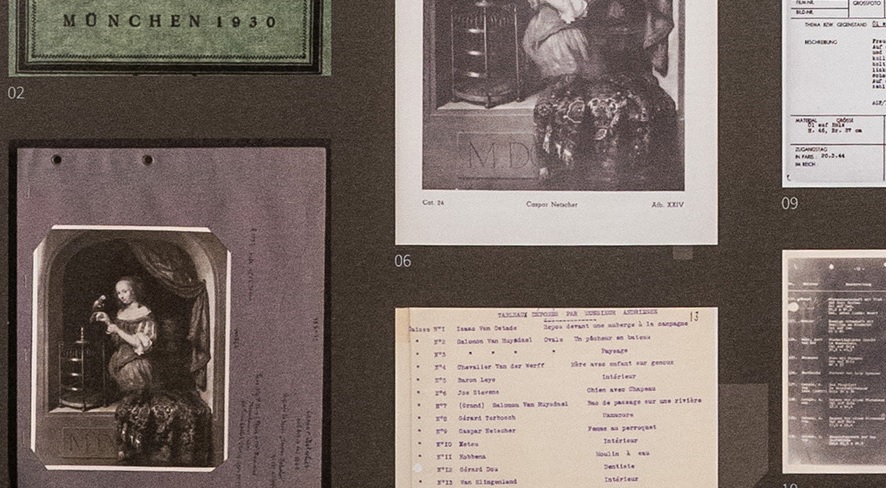

The Andriesses were socially prominent benefactors of charitable institutions in pre-war Brussels who collected Old Master paintings and tapestries. Following their dramatic escape via France and Portugal to New York in 1940, their collection of paintings and tapestries was looted during the Nazi occupation of Belgium. Some of the collection remains missing.

“Through archival documentation, we have pieced together the biographies of the Andriesses and the journey of their nearly forgotten collection, from its seizure during the Nazi occupation to its partial recovery after the war,” explained exhibition curator Anne Uhrlandt, Research and Documentation Officer at the Jewish Digital Cultural Recovery Project (JDCRP).

As a precaution before the war, Jewish families deposited their artworks for safekeeping at the Royal Museum of Art and History at Cinquantenaire Park in Brussels. So did also the Andriesses who entrusted their art and textile collection to the museum in 1939. But during the war, the collection (28 boxes of paintings, 5 tapestries and 17 oriental carpets) was confiscated by the Nazis and transferred to its headquarters in Paris.

Tapestry in need of restoration

One of the most remarkable objects, which ended up in the hands of Nazi war criminal Hermann Göring, was the tapestry Winter, a Brussels tapestry from the 17th century. The tapestry, designed by a leading tapestry workshop, depicts a woman holding a majestic red curtain. Behind her is a two-faced character, possibly the Roman god Janus, a reference to the month of January. At the top, the Latin inscription “Hieme” (= Winter) can be seen.

Winter. Credit: Royal Museums of Art and History

After the war, allied forces recovered the tapestry and it was returned to Belgium. When Elisabeth visited Brussels in 1948, she donated the tapestry to the museum in memory of her husband. During all years since then, the tapestry was largely forgotten in a storage and was not exhibited because of its bad shape.

The tapestry is now temporarily shown in the royal museum’s famous tapestry section. It looks worn out but the colors are still surprisingly clear. Sylvie Paesen, archivist at the museum, told The Brussels Times that the tapestry had been badly restored over the years and would need an urgent restoration. The museum is currently looking for sponsors.

Recovery of looted art

Geert Sels, a culture journalist at De Standard and author of the book Art for the Reich: In Search of Nazi-Looted Art from Belgium (2022, in Dutch and French), has investigated the topic for several years. At the opening of the exhibition in Mechelen, he told the audience about the many details he had uncovered about the fate of the Andriesse collection.

When he started his investigative study in 2014, he had to start from scratch. His book has been described as an appeal to the Belgian government to tackle the sensitive issue of Nazi-looted thoroughly. Although there is a digital database (lootedart.be), based on declarations after the war on lost art, it gives only an indication of what is missing. In most cases, the provenance of the art works in the database is incomplete.

Belgium established for a brief period a research commission but it was not followed up by a restitution commission as in other countries that had been occupied by Nazi-Germany. The issue has been discussed in the Flemish parliament but has not yet resulted in any legislation. Some looted artworks are known to be exhibited at Belgian museums and are claimed by descendants to the owners.

On a positive note, a looted 17th-century painting by Jacob Jordaens was recently recovered from France to Mechelen. The painting had been stolen in 1940 from the house of Joseph Scheppers de Bergstein, a member of the Belgian resistance. In this case no court was involved. The descendants of the person who had kept the painting suspected that it had been looted and decided to return it to its rightful owners.

“Stolen Jewish Legacies: The Fate of the Andriesse Collection” is an exhibition created by the JDCRP, in collaboration with the Kazerne Dossin Memorial, Museum and Research Center on Holocaust and Human Rights; the Jewish Museum of Belgium; and the Federal Public Service Economy (Economy Ministry of Belgium).

“The contribution of the Andriesses to Belgian cultural life has acquired a vibrant afterlife through this exhibition, just as we had hoped,” Deidre Berger, Executive Board Chair of the JDCRP, told The Brussels Times. “It demonstrates the great potential of recreating lives and cultural contributions based on archival sources.”

The Foundation she leads is working with artificial intelligence to create a digital archival repository that will document the records of the theft of Jewish cultural property by the Nazis and their collaborators. The digital database is expected to become cross-searchable in Spring 2025.

M. Apelblat

The Brussels Times