Belgium should heed the lessons of the past in the face of the continuing threat posed by present-day dictatorship and disregard for the law, according to historian Patrice-Emmanuel Schmitz.

Author of a new biography of Émile de Cartier de Marchienne, Belgium’s defiant Ambassador in London during World War II, Schmitz says the country is confronted with the same fundamental question today as it was in 1940: “Do we fold or resist?”

He argues that Belgium should be inspired by the actions of de Cartier, who refused to be cowed or give up hope after King Leopold III controversially ordered his army to surrender, 18 days after Hitler’s forces invaded.

“Eighty years on from the end of the war, current events remind us of what we should do in the face of dictatorship, violence and disregard for the law,” declares Schmitz.

Even smaller countries like Belgium should stand firm against dictators, he says. “They must play their assigned and accepted role in a global EU defence, if possible with allies such as UK, Canada and the US.

“A country’s size is not important,” he adds. “The priority is to define everyone's role and stick to it. For that we require an EU general staff, but not to direct ground operations. We don't have and don't need a unified army. Armies are and remain national with their traditions and capabilities, but we do need strong coordination to establish a solid industrial base that meets needs and avoids duplications.”

For the avoidance of doubt, he clarifies that his remarks about dictatorships “certainly” refer to Russian leader Vladimir Putin in particular.

Heroic figure

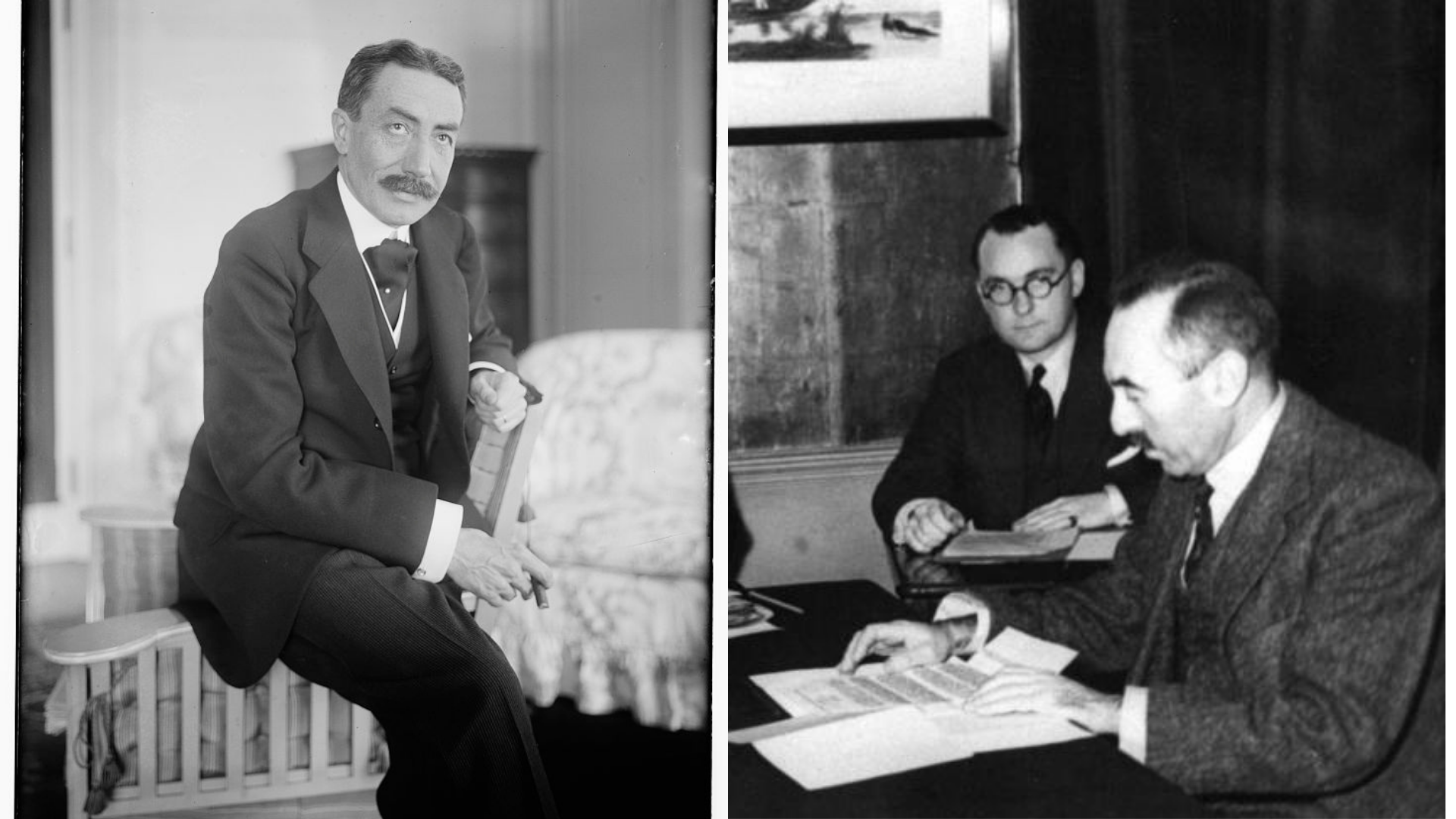

Returning to his book, the author states that he was drawn to writing about Schaerbeek-born de Cartier when he discovered – to his surprise – that that no-one had produced a biography of the diplomat, whose father was Belgian and mother British.

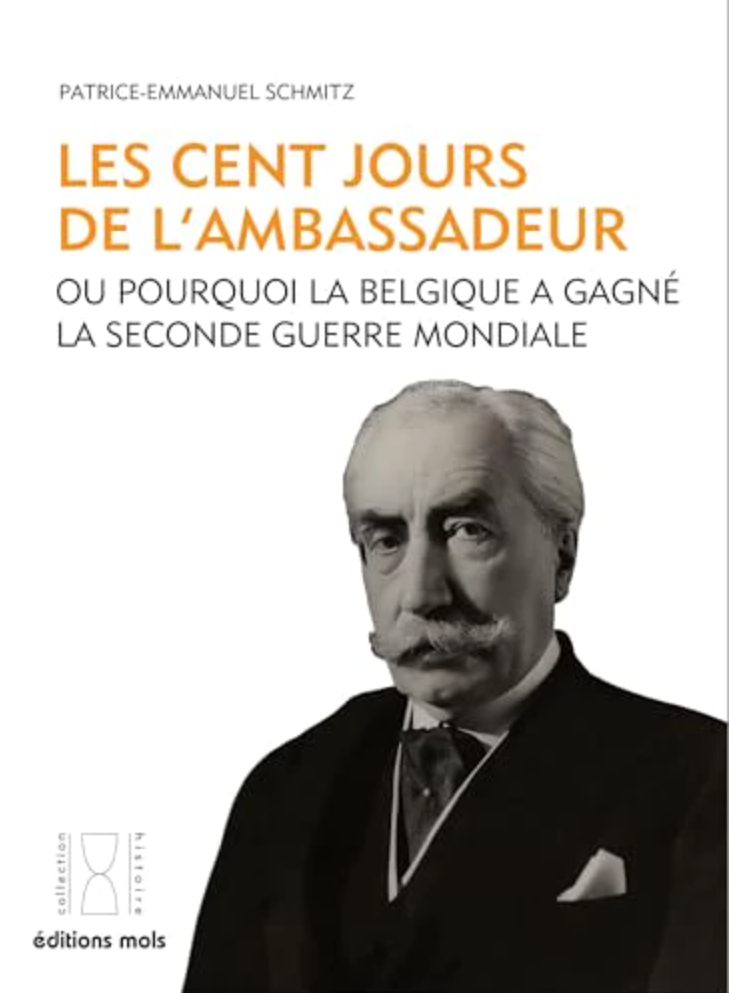

Schmitz finished the manuscript in six months after research at the de Cartier archive in Arendonck, close to the Dutch border. Entitled ‘Les cent jours de l’ambassadeur: Ou pourquoi la Belgique a gagné la Seconde Guerre mondiale’, the work is currently available in French but a Dutch translation is on the way and Schmitz hopes it will also appear in English.

Les cent jours de l’ambassadeur: Ou pourquoi la Belgique a gagné la Seconde Guerre mondiale by Patrice-Emmanuel Schmitz is published by Mols

While de Cartier’s wartime impact has largely been overlooked or forgotten over the years, the author presents him as a heroic figure who should be remembered for keeping Belgium on the right side. De Cartier, who had been the country’s ambassador in London for 13 years in 1940 and whose retirement had been delayed several times, was shocked to learn that the King had capitulated. He knew it meant he would be a prisoner and used as a bargaining chip by the Third Reich, according to Schmitz.

When Belgium’s divided government fled in disarray to France, 69-year-old de Cartier refused to give up. He relentlessly rallied ministers to the Allied cause, “despite a majority believing that Britain would sign a peace deal with Hitler to save its Empire”.Belgium sought to surrender a second time in June 1940 but, in an act of wily statecraft, de Cartier took it upon himself not to deliver a defeatist telegram from Foreign Minister Paul-Henri Spaak to his British counterpart Lord Halifax. The envoy read it to Halifax instead – having first taken the precaution of watering down the content.

"The supreme art of diplomacy is the transformation of a defeat into a victory – and de Cartier was key to ensuring that Belgium ended up in the camp of the victors at the end of the war,” states Schmitz.

De Cartier turned to another old hand, the formidable General Victor van Strydonck de Burkel, to set up a base in Tenby, South Wales, for Belgian soldiers who had escaped to Britain. They would later play their part in the liberation of the country after the D-Day Landings.

Defence spending

De Cartier passed away on 10 May 1946, almost exactly a year to the day after the Allied victory over Germany. At his funeral, the British honoured his courage with an unprecedented 19-gun salute in London’s Hyde Park. For Schmitz, speaking from his home in Corroy-le-Château, it is not difficult to imagine how the fearless ambassador might have responded to the challenges of the present day. “Resist!”

Given the current international context, the author strongly supports Belgium’s recent decision to spend more on defence after decades of backsliding. Last year the previous government allocated only 1.3% of its GDP to defence, making it fourth from last among the 31 NATO allies with armed forces – a source of “national shame” according to new Defence Minister Theo Franken.

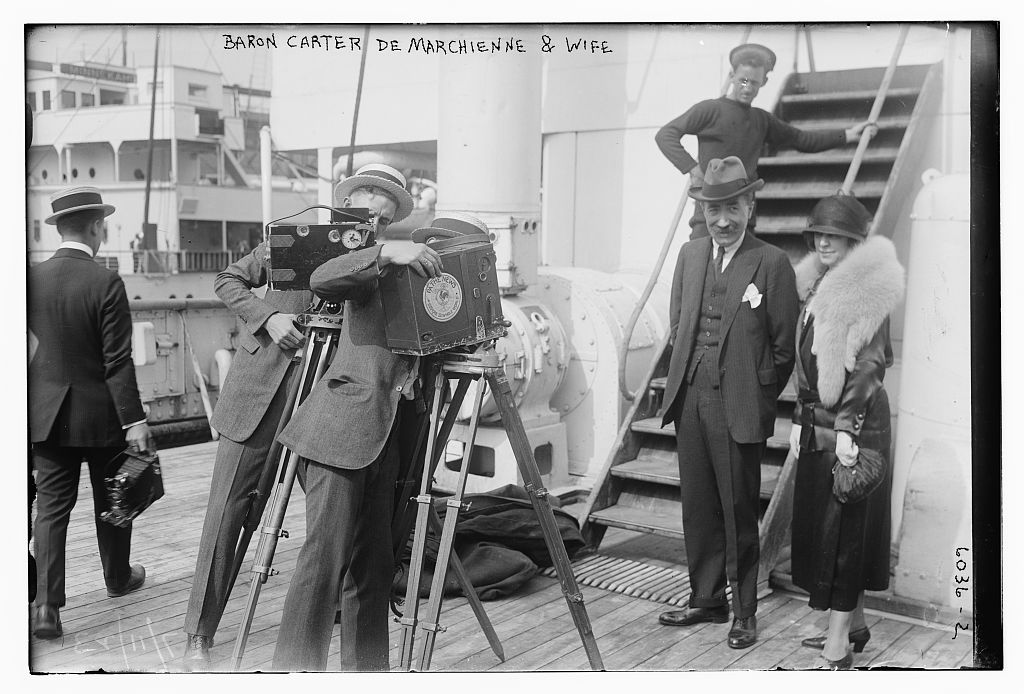

Photograph shows Baron Emile-Ernest de Cartier de Marchienne, the first Belgian Ambassador to the US with his wife Dow. Source: Library of Congress / Flickr Commons project, 2021

Schmitz, who is also a lawyer and external advisor to the European Commission, says Belgium should aim to reach more than 2% “as soon as possible in 2025”. He is in favour of a “NATO v2.0” treaty to respond to “open questions”.

These include “how it can meet EU aspirations to become a defence actor inside and not against NATO”, as well as how the Alliance can bring in new members like Ukraine and Moldova, while also providing a role for traditionally neutral countries such as Ireland and Austria. Émile de Cartier de Marchienne would surely approve.

Les cent jours de l’ambassadeur: Ou pourquoi la Belgique a gagné la Seconde Guerre mondiale by Patrice-Emmanuel Schmitz is published by Mols, 22,50 euros.